Duke Ellington’s New York Rise

Friday, July 18, 2025 by

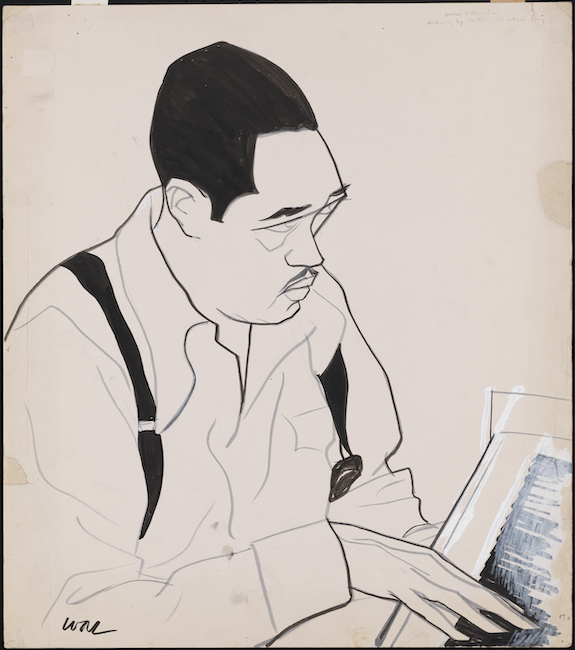

In 2023, when visitors entered the Museum of the City of New York’s centennial exhibition This Is New York: 100 Years of the City in Art and Pop Culture, they were immediately greeted by the pulsating rhythms of “Daybreak Express,” composed by groundbreaking jazz pianist Duke Ellington. The tune is as feverish as it is relentless, and MCNY curators selected it specifically for its evocation of the New York City subway’s frenetic pace. Further along in the exhibition’s “Tempo of the City” gallery, early sheet music from the 1941 masterpiece, "Take the 'A' Train," composed by Billy Strayhorn and made famous by Ellington's band, is displayed behind a glass vitrine. For Ellington, widely credited with Louis Armstrong as one of the two founding fathers of jazz music, the subterranean system of transit synonymous with New York City was clearly never far from mind.

But who was this New Yorker whose talent and brilliance changed American music forever, and how did the city shape his work?

On April 29, 1899, some 225 miles south of Gotham in Washington, D.C., Daisy Kennedy and James Edward Ellington gave birth to a baby boy. They named him Edward Kennedy Ellington. Eventually, he would be known the world over simply as “Duke.” The Ellingtons resided in the nation’s capital, which was then considered the center of urban middle-class Black America. Edward’s mother was protective and doting, and when her son was hit in the head with a baseball as a child, she barred him from playing sports and insisted he take up the piano.[1]

The District of Columbia had a long history of producing supposedly “respectable” musicians, but D.C.’s tight-knit Black community taught young Duke to “overcome the destructive effects of racism with patience, an iron will, and the sure conviction that any goal was within his grasp.” By the 1920s, Harlem supplanted the District as the nation’s Black cultural epicenter. Duke, already experiencing some success in the D.C. music circuit, decided to take a bite of the Big Apple. In 1923, along with bandmates Sonny Greer and Otto “Toby” Hardwick, he headed to Manhattan.[2]

Duke tried to find his way in the New York music scene. Surviving off food served at rent parties and the few dollars he and his bandmates could scrape together, he eked out whatever gigs he could book. This was, however, the height of Prohibition, and opportunity abounded in the countless illegal speakeasies and nightclubs that dotted New York’s streets. In September of that year, Duke got his big break and was booked for an engagement at the Hollywood Club, later renamed the Club Kentucky. A nightclub in midtown Manhattan that was, like so many others, silently backed by gangsters, the Kentucky was unique in that it was racially integrated. Black patrons and entertainers, along with nocturnal New Yorkers of every stripe, crowded the dingy joint to hear Ellington and his band’s revolutionary sound.

The Kentucky’s environment of plurality fostered musical growth (and flexibility) in Ellington and his company. “Answering requests,” Ellington remembered, “we sang anything and everything – pop songs, jazz songs, dirty songs, torch songs, Jewish songs.” To top it off, they were making money. “Sometimes, the customer would respond by throwing a twenty-dollar bill,” recalled bandmate Sonny Greer.[3] In 1926, Ellington began a business relationship with manager Irving Mills, a pugnacious promoter who got his start in Tin Pan Alley. This West 28th Street block housed a collection of music publishers and songwriters in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Propelling the band to new heights (while compensating himself greatly for the trouble), Mills arranged for Ellington to broadcast his performances from the Kentucky over the burgeoning medium of the radio, allowing Duke’s sound to reach new audiences via the airwaves by that year’s close.

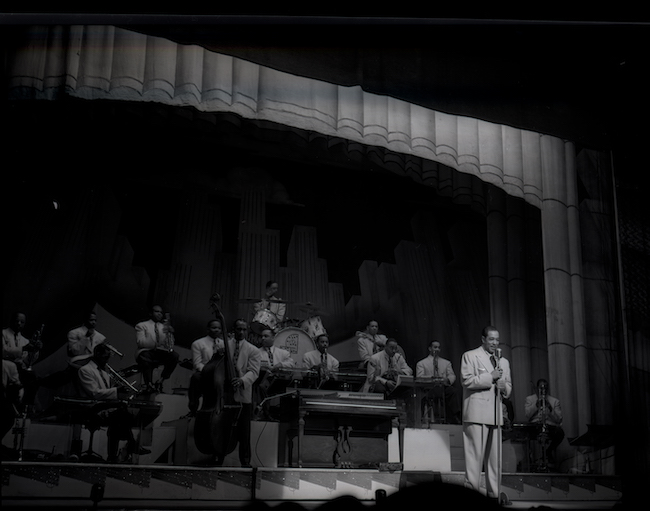

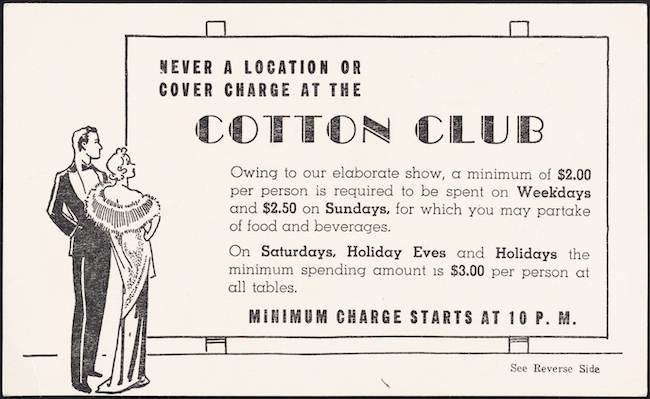

While Kentucky was Duke’s launching pad, it was at the Cotton Club on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem that he became a star. The club was run by Irish-English gangster Owney Madden and his associates, among them Arnold Rothstein, the mobster notorious for fixing the 1919 World Series. In 1923, Madden and company purchased the venue, formerly known as the Club Deluxe, from retired boxer Jack Johnson, the nation’s first Black heavyweight champion. Johnson’s foray into the nightclub business was a failure, probably through no fault of his own. Many blamed the Deluxe’s flop on Johnson’s interracial romances, which elicited disapproval from white New Yorkers and some Black Harlemites. Under new management, the club was renamed the Cotton Club, and soon became Upper Manhattan’s most exclusive haunt – obscenely expensive and inflexibly segregated. Black musicians like Duke Ellington who performed on stage at the Cotton Club were entirely barred from its audience.[4]

Madden hired Joseph Urban, the Viennese stage designer who worked for Broadway visionary Florenz Ziegfeld, to revamp the club. Urban created a set replete with racialized images of the Old South, including a bandstand meant to resemble a plantation mansion. Waiters wore red tuxedos as if they were butlers during Antebellum, and dancers wore short skirts and elaborate costumes of feathers. New Yorkers in the know agreed that the music was better at Small’s Paradise and Connie’s Inn and the dancing was better at the Savoy Ballroom, but for wealthy white pleasure seekers visiting Harlem after hours, the Cotton Club was a smashing success.[5]

In 1927, following the death of the Cotton Club’s bandleader and the unwillingness or inability of several other musicians to take over the job, Duke and his mates auditioned to become the house act at Madden’s Harlem hotspot. Soon after, while they were touring in Philadelphia for Clarence Robinson’s revue Dance Mania, Irving Mills showed up with the contract ready to sign. They got the gig.

It was through his music that Ellington castigated the club’s policy of racial segregation. The same year that he became the Cotton Club’s bandleader, he recorded “Black and Tan Fantasy,” the title of which contained a double entendre. Black and tans were not only a popular alcoholic drink, no doubt served at the Cotton Club, but also a slang term for racially integrated clubs. Ironically, it was at what amounted to a Jim Crow establishment that Duke Ellington, the prideful and elegant Black composer, made his name. He broadcast live from the club several times a week beginning in 1928, not just locally, but nationally. For the first time, white families in the American hinterland could hear his unique and exciting form of urban Black American music.[6]

Ellington continued his career after the Roaring Twenties concluded. In the following decades, he churned out some of his most important tunes, including “Sophisticated Lady,” “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing),” and “Drop Me Off in Harlem,” which is featured in This Is New York’s “Songs of New York.” He also remained a committed New Yorker, even creating a symphonic ode to his adopted neighborhood in 1950, simply titled “Harlem,” which he later presented to President Harry S. Truman. The genteel impresario spent his final years living on West 106th Street and Riverside Drive. Following his death on May 24, 1974, only a few weeks after his 75th birthday, West 106th Street was renamed in his honor as Duke Ellington Boulevard. In 1997, a large memorial sculpture to the jazz genius was erected in Central Park near 110th Street and 5th Avenue, an intersection mere blocks from the Museum of the City of New York that has since been redubbed Duke Ellington Circle. Yet Duke’s legacy goes far beyond the renaming of streets or intersections. Ellington’s catalog of music remains timeless, fresh, and deeply moving well into the twenty-first century. Just “take the ‘A’ train” to Harlem or visit This Is New York if you need a reminder.[7]

[1] A.H. Lawrence, Duke Ellington and His World (Milton Park: Routledge, 2003), 1-3; Mark Tucker, “The Renaissance Education of Duke Ellington,” in Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance: A Collection of Essays (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1993), 113;

[2] Tucker, 123; Donald L. Miller, Supreme City: How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014), 507.

[3] Duke Ellington, Music is My Mistress (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 1973), 72; Miller, 511.

[4] Lawrence, 106.

[5] Lawrence, 106-108; Miller, 106.

[6] Miller, 517.

[7] Rick Lyman, “After an 18-Year Campaign, An Ellington Memorial Rises,” The New York Times, July 1, 1997, C9-10; “West 106th St. Renamed Ellington Boulevard,” The New York Times, December 28, 1977, B3.