Beyond Suffrage: “A Unifying Principle” Understanding Intersectionality in Women’s Activism

Social Studies

Overview

Through rhetorical and visual analysis, students will explore the history of intersectionality within the women’s movement throughout the 20th century and understand how the related power dynamics of race, class, gender, and sexual orientation have shaped the goals of many women’s right’s activists.

Student Goals

- Students will be able to understand and articulate the concept of intersectionality: the idea that all individuals possess many identities—such as race, gender, or sexual orientation—which cannot be separated and understood apart from each other.

- Students will understand the history of intersectionality within women’s activism and the impact it has had in shaping the suffragist, civil rights, and the women’s liberation movement.

- Students will explore and express nuanced and overlapping aspects of their identities and share with their peers.

Common Core State Standards

Grade 5:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.5.2

Determine two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported by key details; summarize the text.

Grades 6-8:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.6

Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts).

Grades 11-12:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.4

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

Key Terms/Vocabulary

Intersectionality, Identity, Multiplicity, Inclusion, Exclusion, Sexism, Discrimination, Racism, Third World, Triple Jeopardy

Key Figures

Sojourner Truth, Mabel Lee, Pauli Murray, Frances Beal, Ivy Bottini, Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, Linda Sarsour

Organizations

National American Woman Suffrage Association, National Association for Colored Women, National Organization for Women, Third World Women’s Alliance, Radicalesbians, Lavender Menace, Women’s March on Washington

Introducing Resource 1

Despite their demands for equality regardless of sex, suffragists themselves were often divided by issues of class and race. Though many early white suffragists had opposed slavery and joined the abolitionist movement, the passage of the 15th Amendment (which prohibited state and federal governments from denying citizens the right to vote based upon race, but not sex) created a split within the movement. Some activists like Lucy Stone campaigned for the amendment in the hope that an end to racial discrimination in voting laws would pave the way for equal protections on the basis of sex. Others, including Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and former slave and activist Sojourner Truth, refused to support any suffrage amendment that did not include women. But some suffragists who criticized the 15th Amendment on the basis of sexism used racist rhetoric to protest women’s exclusion from the vote. Elizabeth Cady Stanton argued that white women were more deserving of the vote than black men. The country needed “educated suffrage,” she said; including former slaves and immigrants as voters would bring "pauperism, ignorance, and degradation" to politics.

By the early 20th century, Stone, Anthony, and Stanton had reconciled and formed the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the largest national suffrage organization. NAWSA took a moderate, mainstream approach to winning the vote, focusing on recruiting white, upper- and middle-class women into its ranks as members and donors and turning away many of the black suffragists who sought to join the Association. In part, NAWSA rejected black suffragists in an effort to appeal to white southern women, many of whom supported Jim Crow laws that kept black men from voting and were not interested in extending the vote to black women.

Not surprisingly, black suffrage organizations and their allies were critical of NAWSA. In 1912, Mary Church Terrell, leader of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), argued in an issue of the Crisis: “What could be more absurd than to see one group of human beings who are denied rights which they are trying to secure for themselves working to prevent another group from obtaining the same rights?” Working-class women too often felt alienated by NAWSA’s tactics and members. Harriet Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, joined with labor organizer Rose Schneiderman to form the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women to address the needs of working women, particularly immigrants, in addition to advocating suffrage.

Below is a flyer circulated by National American Woman Suffrage Association and the Woman Suffrage Party. “To the 8,000,000 Working Women in the United States” appeals to working women to support and join the suffrage movement by arguing that votes for women would help secure protective labor laws.

“To the 8,000,000 Working Women in the United States,” National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1915–17, Collection of Ann Lewis and Mike Sponder

Document Based Questions

- What is the basic argument of this flyer?

- Who is this flyer addressing? How many different audiences can you identity?

- According to this flyer, how would the vote help working women?

- Why would the National American Woman Suffrage Association address both men and women in this flyer? How might working men benefit from women’s suffrage?

Introducing Resource 2

Although black feminist scholar Kimberlé W. Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality (the idea that all individuals possess many identities that cannot be separated and understood apart from each other) in 1989, Pauli Murray was living out the struggles of intersectional feminism in her groundbreaking work as an activist and legal scholar dedicated to racial and gender equality beginning in the 1930s. Challenging the ways in which black women were marginalized in the women’s movement and the sexism that she faced in black activist organizations, Pauli Murray articulated in her writings the ways in which women like herself—black, feminist, and queer—faced overlapping forces of oppression, and the way in which laws could be constructed to protect the multiplicity of individuals’ identities.

Pauli Murray graduated as the only woman in her class and as valedictorian from Howard University’s law school in 1944. In her senior thesis, she argued that Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court case that had created the racial doctrine of “separate but equal,” was discriminatory, a theory that the lawyers of the NAACP would use nearly ten years later in their argument in the case Brown v. Board of Education that struck down “separate but equal” laws across the country. She went on to publish States’ Laws on Race and Color in 1950.

Murray ran for New York City Council in 1949 on the Liberal Party ticket using the slogan “good government is good housekeeping.” She came in second only to the Democratic Party contender, but never ran for office again; instead she forged a multifaceted career as a lawyer, writer, and priest. Her work helped add “sex” as a protected category to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and, with human rights activist and lawyer Dorothy Kenyon, she influenced the Supreme Court’s 1975 decision requiring women’s jury service.

Murray’s legal work also greatly impacted ACLU lawyer and future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who named Murray as one of the co-authors of a legal brief she submitted in Reed v. Reed in 1971, a case which marked the first time the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, intended to protect against racial discrimination, was applied to a case of sex discrimination.

Below is an excerpt from a letter Murray wrote to the National Organization for Women in 1967 where she explains her overlapping identities and her search for a community which would embrace her whole self.

“I cannot allow myself to be fragmented into Negro at one time, woman at another, or worker at another, I must find a unifying principle in all of these movements to which I can adhere.” — Pauli Murray, Letter to the National Organization for Women, 1967

Document Based Questions

- What does Pauli Murray mean when she writes that she feels “fragmented” into different identities at different times? What might cause her to feel that way?

- Why is it important for Murray to find a “unifying principal” she can follow? How would you describe that principle?

- What emotions do you feel as you read Murray’s words? Why do you feel that way?

- Can you think of a time when you felt fragmented, or forced to downplay certain aspects of your identity? When was that or how would you describe that time?

Introducing Resource 3

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s helped inspire women’s liberation by not only providing a model for activism, but also because many black and white women who had fought for racial justice had faced sexism within civil rights organizations. These young activists took the organizing skills and personal empowerment they gained from participating in Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) campaigns in the South—such as the famous Freedom Rides aimed at integrating interstate bus travel—and turned them toward their own liberation.

The Third World Women’s Alliance (TWWA) was one of the many new organizations born of the civil rights movement. Originally, an outgrowth of the Black Woman’s Liberation Committee of SNCC, organized by member Frances Beal in 1968, the TWWA soon split off from SNCC in order to include Puerto Rican women, becoming an independent organization. The Alliance aimed to address poverty, welfare rights, and reproductive justice for all women—all issues they critiqued white feminists for excluding. In 1971 the TWWA launched Triple Jeopardy, a newspaper addressing what they termed the “triple oppression” of third-world women: racism, sexism, and imperialism, all rooted in capitalism.

Third World Women’s Alliance, September–October 1971, Lent by the Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University

Document Based Questions

- How are the women on this cover depicted?

- What is the tone (mood) of this newspaper cover? What reaction does it provoke (bring out) from its reader?

- “Third World” was a term used to describe countries in Asia, Africa, and South America that were not allied with the United States or the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Many of these nations were former colonies that declared independence in the mid-20th century and were growing politically and economically. Why do you think the Third World Women’s Alliance chose this name for their organization?

- Drawing from the other text/words on the cover, why might the Third World Women’s Alliance call their magazine Triple Jeopardy? What do you think that term means?

- Are there other words you might add to the cover apart from “sexism,” “racism,” and “imperialism”?

Introducing Resource 4

Lesbians often struggled to find a home in the mainstream women’s movement, which could be openly hostile to their participation. At a 1969 NOW meeting, Betty Friedan characterized a group of outspoken lesbians as a “lavender menace” that could derail the broader goals of feminism, and many lesbian members, including NOW New York City president Ivy Bottini, were expelled the following year. A contingent from the New York-based organization Radicalesbians responded by appropriating the name and creating a group they called “Lavender Menace,” which argued that lesbianism was central to feminist politics. The informal group interrupted the Second Congress to Unite Women in New York City in 1970, wearing Lavender Menace t-shirts like the one shown here. They were greeted with cheers from allies in the audience. By 1971 Friedan and NOW had reversed course, openly acknowledging lesbian rights as women’s rights.

Linda Rhodes, Arlene Kushner, and Ellen Broidy, 1970, Photo by Diana Davies/Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library

Document Based Questions

- What does it demonstrate about mainstream feminism in 1969 that Betty Friedan believed that including lesbians under the umbrella of the National Organization for Women would “derail” the goals of the organization?

- (For teachers who are also teaching the lesson “Working Together, Working Apart: How Identity Shaped Suffragists’ Politics) What parallels do you see between the National American Women’s Suffrage Association’s exclusion of women of color and the National Organization for Women’s exclusion of lesbian organizers?

- Why might women like Ivy Bottini fight for inclusion of lesbian rights within NOW’s platform? Why would a group like the Radicalesbians form and “reclaim” the term Lavender Menace?

- (For teachers who are also teaching the lesson “What’s Wrong with Equal Rights?”): Can you think of other terms that women activists have reclaimed? What are some of the pros and cons of reclaiming words?

- In the 1970s, the Radicalesbians challenged Ms. Magazine for not covering lesbian issues. What other issues would you want a feminist magazine like Ms. to address today? Why?

Introducing Resource 5

On January 21, 2017, five million protestors--both women and men--from New York and around the world took to the streets to protest the inauguration of Donald Trump and to demonstrate for women’s rights. Four New York women—Bob Bland, Tamika Mallory, Carmen Perez, and Linda Sarsour—led planning for the Women’s March in Washington, D.C. A concurrent march in New York City drew 400,000 participants.

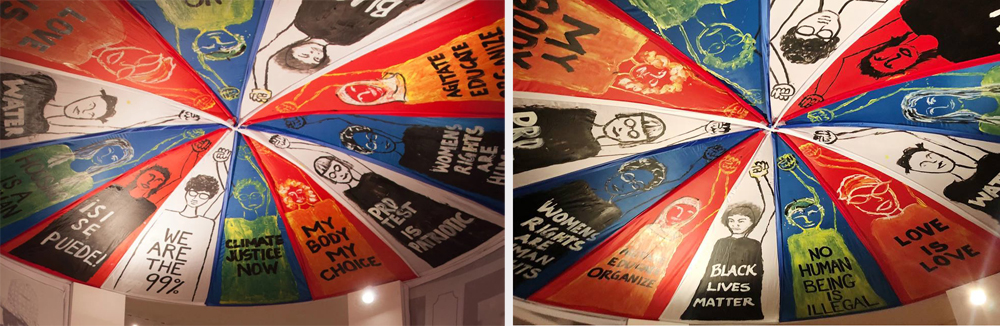

This parachute was created for the New York City women’s march on January 21, 2017. It features a diverse range of 12 women activists, artists, and politicians, including six New Yorkers—Shirley Chisholm, Jane Jacobs, Denise Oliver, Yuri Kochiyama, Audre Lorde, and Lolita Lebron—alongside Winona La Duke, Angela Davis, Frances Pauley, Ruby Bridges, Dolores Huerta, and Malala Yousafzai. The parachute was held aloft during the march to symbolize collaboration and inclusion—two themes women have grappled with throughout multiple generations of the feminist movement.

Slogans include: Black Lives Matter, No Human Being is Illegal, Love is Love, Water is Life, Housing is a Right, Si Se Puede, We are the 99%, Climate Justice Now, My Body My Choice, Protest is Patriotic, Women's Rights are Human Rights, Agitate, Educate, Organize.

“We Carry Them With Us, They Lifted Us Up,” Acrylic paint on nylon parachute, Designed by Elizabeth Hamby, Priscilla Stadler, Bridget Bartolini, and Hatuey Ramos-Fermin, 2017

Document Based Questions

- What issues do you see represented on the parachute? Have you heard any of these slogans before?

- Why are the women depicted on this artwork raising their fists? How does that pose make you feel?

- Why might the artists have chosen to demonstrate with a parachute at the Women’s March?

- What are some of the ways in which the activists shown in this parachute are connected? How do their various slogans relate to each other?

- Who are some other activists and slogans you might add to this artwork?

Activity

In this exercise, students will create a design for a mural exploring the theme of intersectionality.

Just as organizers, activists, and artists must develop a design and then present it for approval to their community when creating a mural in New York City parks or schools, students will break into small groups and together create a mural design, write a statement of artistic purpose, and then explain their design to their classmates. The activity can end with the presentation of the design, or teachers may choose to incorporate a visual component by having students use artistic materials to paint their designs.

Using the “We Carry Them With Us, They Lifted Us Up” parachute as inspiration, each group’s mural should highlight specific issues that belong to an intersectional mission for social change and the historic and contemporary activists who have fought for those issues. Teachers may also direct students to the mission statement created by the organizers of the Women’s Marches of January 2017 as a starting point for considering issues that could be incorporated in an intersectional mural. View the mission statement.

Step 1: Divide students into small groups. Present them with the mural challenge:

- Our school wishes to collect designs for a mural celebrating the theme of intersectionality. We have been given a sentence to help inspire potential designs—“We believe that Women’s Rights are Human Rights and Human Rights are Women’s Rights.”

Step 2: Ask students to spend ten minutes brainstorming in their small groups to create a design that speaks to the mural’s theme. Some questions that students should ask themselves as they brainstorm are:

- How do we define intersectionality? What are some words and ideas that come to mind when we hear that term?

- What kinds of issues do we think are included under the umbrella of women’s rights? Why does the design challenge proclaim that “women’s rights are human rights?” Why are they the same?

- Who are some people that come to mind when we think of intersectional activism? What characteristics or qualities do they have in common?

(For teachers: if students need help, teachers can present them with a few historical figures whose activism exemplifies intersectionality. A few choices might include):

-

- Sojourner Truth: African American abolitionist and women’s right activist whose most famous speech asked “Ain’t I a Woman?”

- Mabel Lee: Chinese suffragist who marched in support of women’s right to vote, even when the law barred Chinese Americans from voting (found in the lesson “Working Together, Working Apart”)

- Pauli Murray: African American civil rights lawyer who fought against racial segregation and sex descrimination

- Sylvia Rivera: Transgender and Latina activist who brought attention to the struggles of homeless and transwomen of color

- Linda Sarsour: Muslim American activist and co-organizer of the Women’s March

Step 3: Ask each group to take twenty minutes to create a design and write a statement of artistic purpose. Students may choose to describe the design in a written document or create visual representations as well. The statement of artistic purpose should include some responses to the following questions:

- Who will be depicted in the mural? Why did your group select these activists? What issues do they represent?

- What is the setting of the mural? Where will the activists be featured? What will surround them in the design?

- Will your design include any words or phrases? Why did you select those specific words?

- What is the title of your mural?

- How does this mural celebrate the theme of intersectionality?

- Why is this mural an important addition to your school?

Step 4: Ask each group to present their design in turn to their classmates. The presentation should tell the class which issues are highlighted, which activists are being included in the design, why they were chosen, and how the design speaks to the theme of intersectionality. Students will answer any questions their classmates may have about each group’s design.

(Optional Step 5: Students will create a small-scale version of their group’s mural design. Students can stay in their groups or work independently to create their murals using markers, colored pencils, butcher paper, collage materials, etc.)

Sources

National American Woman Suffrage Association. To the 8,000,000 Working Women in the United States, 1915–17. Collection of Ann Lewis and Mike Sponder.

Pauli Murray, Letter to the National Organization of Women, 1967.

Third World Women’s Alliance. Triple Jeopardy. Vol 1, no 1 (September–October 1971). Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

Linda Rhodes, Arlene Kushner, and Ellen Broidy, 1970. Photo by Diana Davies/Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library

Elizabeth Hamby, Priscilla Stadler, Bridget Bartolini, and Hatuey Ramos-Fermin. “We Carry Them With Us, They Lifted Us Up.” New York, 2017. Acrylic paint on nylon parachute.

Additional Reading

Bay, Mia. To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2009.

Cooper, Brittney. “Black, queer, feminist, erased from history: Meet the most important legal scholar you’ve likely never heard of.” Salon.com October 18, 2015. https://www.salon.com/2015/02/18/black_queer_feminist_erased_from_history_meet_the_most_important_legal_scholar_youve_likely_never_heard_of/ (retrieved October18, 2015).

Davis, Angela Y. Women, Race, & Class. New York: Random House, Inc., 1981.

Giddings, Paula. When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 1984.

hooks, bell. Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Lorde, Audre. Zami: A New Spelling of My Name - A Biomythography. New York: Random House, Inc., 1982.

Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries: Survival, Revolt, and Queer Antagonist Struggle. New York: Untorelli Press, 2012. https://untorellipress.noblogs.org/files/2011/12/STAR.pdf

This is a collection of historical documents, interviews, and critical analyses of S.T.A.R. (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) a group that helped transgendered homeless youth and people of color. Contained within are pamphlets distributed by S.T.A.R., as well as interviews with and speeches by Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson.

Mock, Janet. Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2014.

Civil rights lawyer and UCLA professor Kimberlé W. Crenshaw, who developed intersectional theory in a ground-breaking 1989 Chicago Legal Forum article, lays out the importance of intersectional feminism in a one-minute video on August 11, 2017 at the Netroots Nation Conference in Atlanta, Georgia.

https://twitter.com/PPNYCAction/status/896032277062443009

Her Chicago Legal Forum article: https://philpapers.org/archive/CREDTI.pdf

Frances Beal interview, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA 01063

https://www.smith.edu/libraries/libs/ssc/vof/transcripts/Beal.pdf

Contemporary Connections

On September 24, 2015, Dr. Crenshaw published an op-ed entitled “Why Intersectionality Can’t Wait” in the Washington Post arguing for the importance of stressing intersectionality within recent social movements such as the Movement for Black Lives.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-theory/wp/2015/09/24/why-intersectionality-cant-wait/?utm_term=.a2d2a582b1cc

Written by Farah Stockman, this New York Times article, “Women’s March on Washington Opens Contentious Dialogues About Race,” published in the weeks prior to the January 2017 march looks at the way white women and women of color responded to the march leaders’ focus on intersectionality in planning the demonstration.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/09/us/womens-march-on-washington-opens-contentious-dialogues-about-race.html?_r=2

Written by Ruth Padawar and published in the October 15, 2014 issue of the New York Times Magazine, “When Women Become Men at Wellesley” explores the experiences of trans men at women’s colleges in the United States.

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/19/magazine/when-women-become-men-at-wellesley-college.html?_r=0

“Memories of a Penitent Heart” is a joint PBS and Latino Public Broadcasting documentary by filmmaker Cecilia Aldarondo exploring the story of her uncle Miguel and his struggle to reconciling his Catholicism and homosexuality as a Puerto Rican migrant living in New York. http://www.pbs.org/pov/penitentheart/

In a blog post for PBS, journalist Pooja Sivaraman explores the film’s treatment of intersectionality.

http://www.pbs.org/pov/blog/news/2017/07/the-intimacy-and-intersectionality-of-memories-of-a-penitent-heart/

Field Trips

This content is inspired by the exhibition Beyond Suffrage: A Century of New York Women in Politics. If possible, consider bringing your students on a field trip by July 2018! Find out more.

Acknowledgements

Education programs in conjunction with Beyond Suffrage: A Century of New York Women in Politics are made possible by The Puffin Foundation Ltd.