Mastering the Metropolis

New York and Zoning, 1916-2016

November 9, 2016 - April 23, 2017

Back to Past Exhibitions

How tall can New York buildings be? How wide? Where can developers build homes, factories, offices, or stores? Where do New Yorkers live, work, and play?

The character of New York’s varied neighborhoods is governed by a novel set of rules first envisioned by New York reformers 100 years ago – the groundbreaking Zoning Resolution of 1916. Zoning, which was designed to tame the unruly process of free-market real estate development, has continued to shape the city we know today in countless, often unseen, ways.

This landmark law gave birth to the iconic “setback” skyscraper and the modern skyline; to special neighborhoods like the Theater District; to public amenities like pedestrian plazas, and to residential neighborhoods of all shapes and sizes. On the 100th anniversary of America’s first comprehensive zoning resolution, Mastering the Metropolis: New York and Zoning, 1916-2016 will examine the effects of the evolving law and chart the history of the city’s zoning rules and debates to the current day, illuminating how the tools of zoning have reflected a century of evolving ideas about what constitutes an “ideal” city.

Wurts Bros., 120 Broadway. The New Equitable Building, c. 1910. Museum of the City of New York, X2010.7.1.1525.

When the Equitable opened in 1915, it became a symbol of all that was wrong with unregulated development, galvanizing support for the passage of a zoning ordinance. At 542 feet, the structure cast a shadow that covered 7.5 acres.

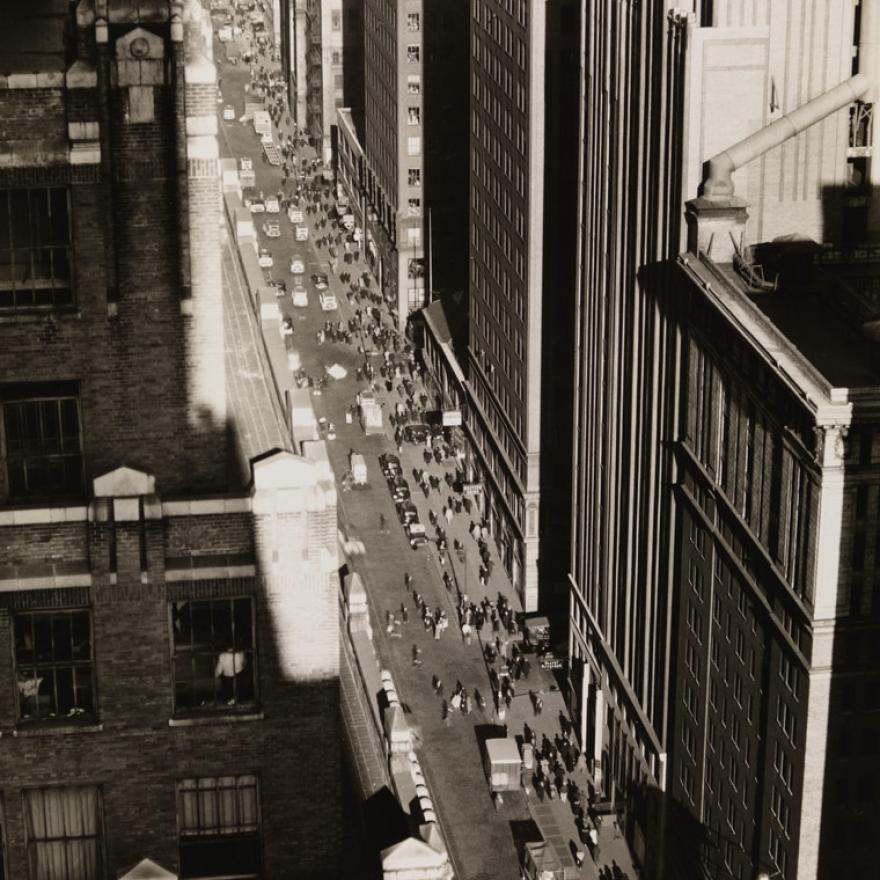

Berenice Abbott, Seventh Avenue Looking North from 35th Street, 1935. Museum of the City of New York, Museum Purchase with funds from the Mrs. Elon Hooker Acquisition Fund, 40.140.229.

The 1916 ordinance gave rise to one of Manhattan’s defining features: its urban “street wall”—the uninterrupted line of buildings along the sidewalks. Because regulations tied base height to street width, buildings rose to a constant height along almost every street.

General Motors Building, 767 Fifth Avenue between 58th and 59th Streets, 1968. Courtesy General Motors LLC. Used with permission, GM Media Archives.

When General Motors opened their building on Fifth Avenue and 59th Street in 1968, it epitomized the effects of the 1961 code. In return for creating a large public plaza and arcade, the developers got a ''zoning bonus'' that enabled them to add floors, creating a 50-story skyscraper.

Rob Stephenson, Domino Sugar Factory, Brooklyn waterfront, 2016. Courtesy of the photographer.

The spread of factories to commercial and residential areas led to calls for the “separation of uses.” The 1916 zoning code was designed to encourage manufacturing to grow around the waterfront and rail lines, areas already dominated by industry.

Rob Stephenson, New Springville, Staten Island, 2016. Courtesy of the photographer.

The 1961 rezoning of Staten Island brought massive residential and commercial development.The residential areas that allowed multifamily homes was reduced to just 0.5 percent of the borough’s total area. Between 1960 and 1967, more than 12,000 single-family homes were built on Staten Island.

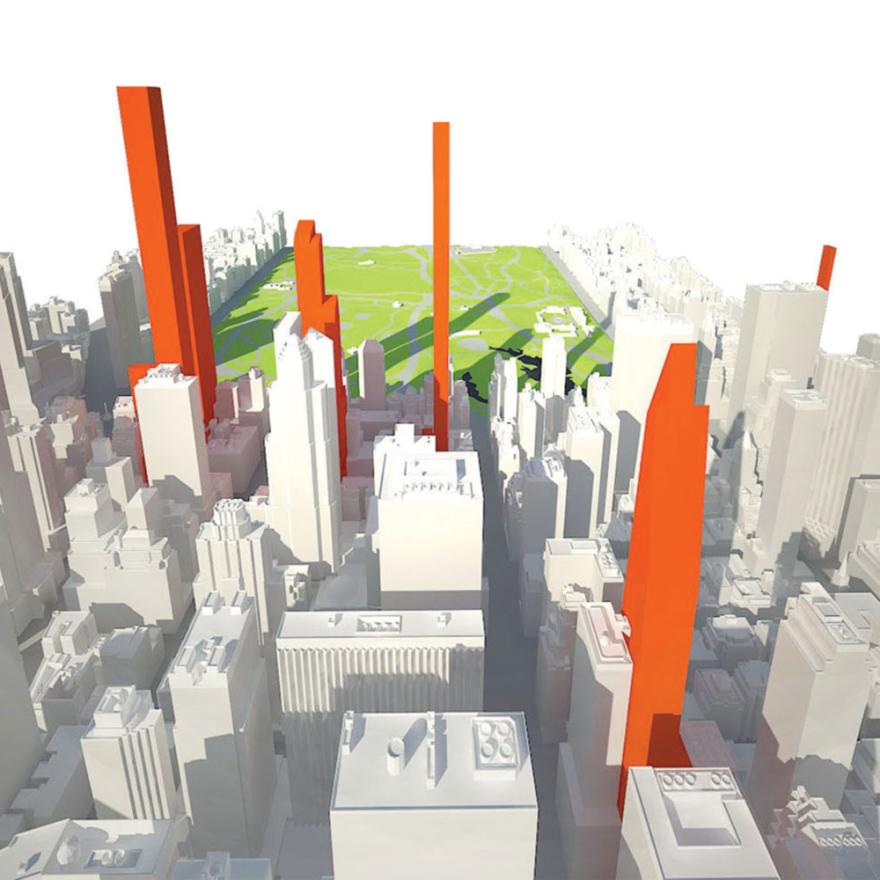

“View North Toward Central Park,” 2013. Courtesy Municipal Arts Society.

The Municipal Arts Society commissioned a study to show how supertalls will cast shadows onto Central Park. While these structures will create longer shadows than the buildings they are replacing, their slimmer frames will reduce the width of the shadows.

Sponsors

Kramer Levin, Lindenbaum Family Charitable Trust, New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, Con Edison, Vornado Realty Trust.

Additional support is provided by: Greenberg Traurig, Tishman Speyer, Bryan Cave LLP, Douglaston Development, Ehrenkranz & Ehrenkranz LLP, General Contractors Association of New York, Goldstein, Hill & West Architects, GoldmanHarris LLC, Harry Maclowe, Jack Resnick & Sons, Inc., Witkoff, Anbau Enterprises, Atlas Capital Group, Ben Kallos, New York City Council, The Durst Organization, Geto & de Milly, Inc., Higgins & Quesebarth, MdeAS Architects, Quinlan Development Group LLC, SJC 33 Owner 2015, LLC, VHB, Acheson Doyle Partners Architects, P.C., Beyer, Blinder, Belle Architects and Planners LLP, Brandon Haw Architecture LLP, Capalino + Company, Carnegie Hill Neighbors, COOKFOX Architects, Cooper Robertson, David G. Greenfield, New York City Council, Development Consulting Services/Michael Parley, Hines, Brenda Levin, Mary Ann and Martin J. McLaughlin, Meister Seelig & Fein LLP, Robert A.M. Stern Architects, Robert I. Shapiro, Vidaris/Robert Limandri, Dattner Architects, Ferguson & Shamamian Architects, FXFOWLE Architects, Laurence Gillman/Gillman Consulting Inc., Robert F. Herrmann, Stephen B. Jacobs Group P.C., PAR Plumbing Co. Inc.

Acknowledgements

Honorary Chair

Carl Weisbrod, Chairman and Commissioner

The City of New York Department of City Planning

Exhibition Co-chairs

Jill N. Lerner, FAIA

Linda Lindenbaum

Michael T. Sillerman

Special thanks to KPF.

The exhibition is presented in memory of Samuel H. Lindenbaum and is co-sponsored by the City of New York Department of City Planning.