Why are Alexander Hamilton and DeWitt Clinton on the Museum's Façade?

Thursday, November 30, 2017 by

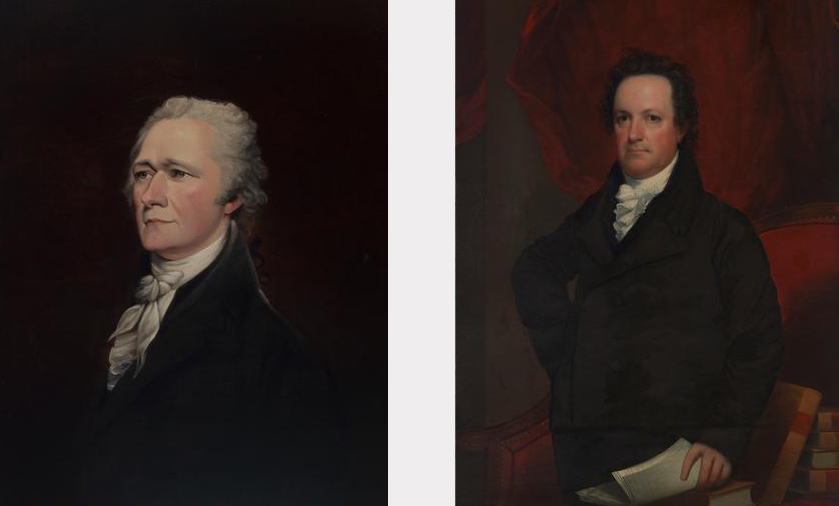

Sculptures of Alexander Hamilton and DeWitt Clinton have been standing in the niches of the Museum’s façade since 1941. We recently welcomed them back home after being away a few months for cleaning and conservation. Curator Steven Jaffe explains why these legendary New Yorkers are worthy of a permanent place at the Museum.

New York City was a cradle of two momentous revolutions: a political and military revolution in 1775-1783, and a commercial one that followed it in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. And two New Yorkers —Alexander Hamilton and DeWitt Clinton—were key players in making those revolutions brilliantly successful.

Born on the island of Nevis in the British West Indies in 1755 or 1757, Hamilton came to New York after being employed as a merchant’s clerk on St. Croix. After studying at Kings College (today Columbia University), he joined a revolutionary volunteer militia company in New York in 1775. Hamilton became General George Washington’s aide de camp and one of his most trusted advisors. After starting a law practice in lower Manhattan following the war, he sometimes collaborated and sometimes jousted with Aaron Burr, also a lawyer, in trials in the city’s courts (indeed, in 1800 Hamilton and Burr successfully defended Levi Weeks, a carpenter accused of killing his paramour, in one of the city’s most sensational murder trials). Hamilton threw himself into New York’s public affairs, leading efforts to reconcile the city’s ex-Tories and revolutionary veterans, co-founding the anti-slavery Manumission Society (1785), founding the New York Post (1801), and creating the Bank of New York (1784), the new republic’s second bank, to facilitate trade and prosperity. As he told Washington, banks gave “a new spring to agriculture, manufactures, and commerce,” thus promoting a strong and diversified national economy.

Brought up to appreciate urban seaports and trade, Hamilton valued mercantile enterprise, credit, maritime commerce, manufacturing, and the idea of a strong central government that could protect all of the above and bind the thirteen new states together. He made his views known in the Federalist Papers (1787-1788) he drafted with fellow New Yorker John Jay and Virginian James Madison, helping to promote the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788. As President Washington’s Treasury Secretary in New York City (the first federal capital) and then Philadelphia, Hamilton created the financial structure of the new American government-- including the Bank of the United States, a public debt in the form of U.S. bonds, and departments for customs enforcement and revenues collection. (When you pay your federal taxes next April 15, blame Hamilton). Fittingly, Hamilton’s portrait also adorns the front of the ten-dollar bill you have in your pocket.

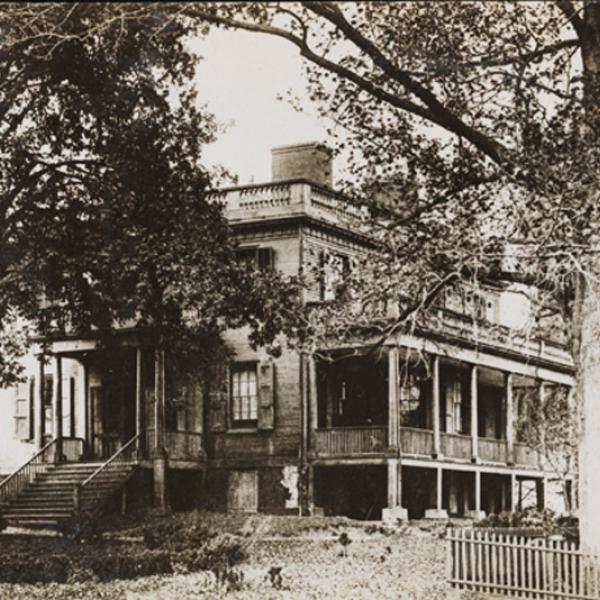

Yet, as two competing visions of America’s future emerged in the 1790s—one favoring trade, finance, centralized power, and ties to Britain, the other valuing agriculture, states’ rights, and the French Revolution—Hamilton’s identification with the new Federalist Party and his conflicts with Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson made him one of the nation’s most controversial figures. Stepping down from his Treasury post in 1795, Hamilton remained a behind-the-scenes force in national politics, even after moving to the Grange, his upper Manhattan estate, in 1802. (Still a prominent lawyer, he would spend up to three hours a day, round-trip, commuting nine miles by road between his rural retreat and his office in lower Manhattan.) Two years later, Hamilton was fatally wounded by Aaron Burr in a duel over political and personal aspersions allegedly cast by Hamilton against Burr. Tragically, the duel was fought at or near the same spot in Weehawken, New Jersey, where Hamilton’s 19-year-old son Philip had also been mortally wounded in a duel defending his father’s honor against political defamation, less than three years earlier.

DeWitt Clinton was a different kind of New Yorker. Born in what is now Orange County, New York, Clinton was more than a decade younger than Hamilton—too young to fight in the Revolutionary War. Unlike the West Indian immigrant, he was born into a powerful dynasty—that of his uncle, George Clinton—paving DeWitt’s way into politics. Clinton was a member of Jefferson’s Democratic Republican Party. But unlike Hamilton, whose political positions remained consistent, Clinton was willing to raise eyebrows by turning against his party when it served his ambitions: in 1812 he ran for the presidency, accepting support from Federalists and dissident Democratic Republicans (although he lost the election to sitting Democratic Republican president James Madison).

Yet, on second glance, Clinton shared striking traits with Hamilton. Like Hamilton, he attended the college now renamed Columbia, and he saw New York City as a political base for his own career. After serving as U.S. Senator in 1802, he filled five terms as the city’s mayor and became a savvy political operator, attaining the governor’s mansion in Albany in 1817. Clinton also shared with Hamilton an animosity toward Aaron Burr, since Burr competed for political prizes in New York that Clinton coveted for himself.

More importantly, Clinton, like Hamilton, was a visionary. Where Hamilton had looked forward to banks, cargo ships, and factories as the engines of New York City’s and America’s greatness, Clinton foresaw that New York City and State would benefit enormously if a manmade waterway could be built connecting the Hudson River with Lake Erie. New York would thereby beat Boston and Philadelphia to the riches of the frontier west, where pioneering farmers were converting forests and prairies into wheat fields. With this waterway completed, New York “will stand… unrivalled by any city on the face of the earth,” Clinton predicted boldly in 1816. Denounced by his political foes as “Clinton’s Ditch,” the 363-mile Erie Canal—built between 1817 and 1825 by the New York State government, with aid from Manhattan banks and investors —stimulated the growth of boom towns across central New York and brought unprecedented wealth to the wharves, warehouses, and merchant’s offices of New York City.

Over the centuries, Hamilton has remained the more famous of the two. (Clinton’s face appeared briefly on the $1,000 bill issued in 1880, but that just can’t compete with Hamilton’s ever-present visage on the ten.) In the end, each man envisioned national growth and the destiny of New York City as inextricably linked, to the advantage of both nation and city. Whether we realize it or not, when we think today of Gotham as the unofficial capital of American finance, culture, and innovation, we are invoking these two founding fathers of the city’s greatness.

Visit New York at Its Core to learn more about how these two important New Yorkers shaped the future of both the city and the United States.

#amexpreserves

Additional support provided by The Barker Welfare Foundation.