The Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic

Tuesday, July 1, 2014 by

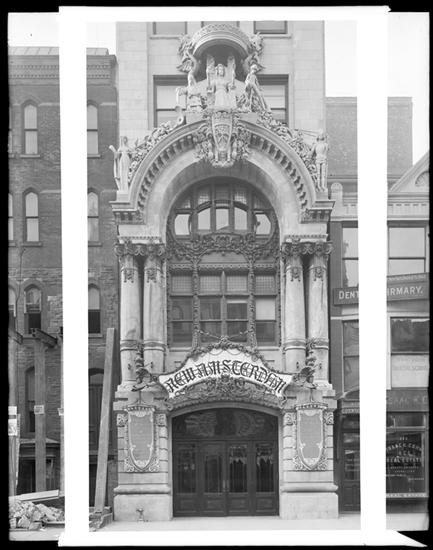

It’s a sweltering July evening in 1915 and the lights have just come up after the finale of a Ziegfeld Follies show at the New Amsterdam Theatre on 42nd Street. You dread walking out into the muggy night and long for a cool escape. But you’re in luck tonight because it’s the premiere of Flo Ziegfeld Jr.’s new revue, the Danse de Follies! You take the elevator from the theatre lobby up to the rooftop garden (you’ve heard it called “the meeting place of the world”) and as the doors open you are met with dancing and the sound of champagne being uncorked. The show starts at midnight and you have work in the morning, but a late night of revelry to escape the stuffy New York summer seems like a small price to pay for the exhaustion of tomorrow.

Earlier that year, Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., tired of seeing his audiences leave after performances of the Ziegfeld Follies to spend money at other people’s nightclubs, staged a second late-night revue in the New Amsterdam Theatre’s underused 680 seat roof-top level with tables, complete with box seats, and a balcony. Ziegfeld mechanized the stage so that it rolled back to reveal a dance floor, and installed a glass walkway that would allow chorus girls to dance right above the customers seated below. Later called the Midnight Frolic, the show was a bit more risqué than the Follies. The girls shimmying down the glass walkway above the audience were reportedly cautioned to wear bloomers but oftentimes the rule wasn’t followed very closely. Audience members were asked to vote for the young lady he or she considered the most beautiful and to state why on cards handed out by the usher. The young lady receiving the most votes during the run of that Frolic series had her salary doubled. One of the audience favorites was the “balloon girls,” who encouraged male patrons to use their cigars to pop the balloons covering the majority of their costumes.

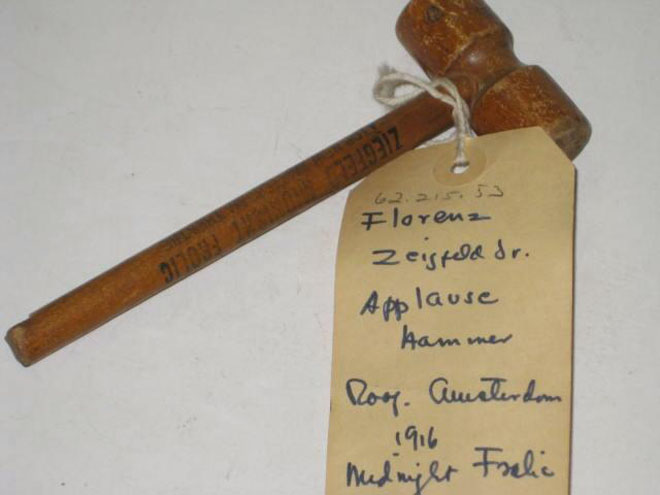

To keep out the rougher elements, Ziegfeld charged a hefty $5.00 cover (roughly $117 today) on top of the ticket price – first row seats went for $3 (approximately $55 today), while orchestra seats went for $2.50 (about $46). Upper class theatre-goers were delighted with the Midnight Frolic’s party-like atmosphere, and the revue became an annual event after its premiere in 1915. Insisting that theater-goers would have sore hands after applauding so much, Ziegfeld provided little wooden hammers at Frolic tables, so audiences could bang out their appreciation.

Image credit: Maker unknown. Wooden applause hammer from Ziegfeld's Midnight Frolic atop New Amsterdam Theatre. ca. 1916. Museum of the City of New York. Gift of Henry Rogers Benjamin, 1962. 62.215.53

The Midnight Frolic often received rave reviews from the New York Times: “The latest edition of Florenz Ziegfeld’s ‘Midnight Frolic,’ which had its first presentation Monday midnight before an audience that embraced all who live and move and have their being in Broadway, out-Ziegfelds all its predecessors. It is like the others only more so. It is a Ziegfeld-Urban-Wayburn show of beautiful women, frocks and tableaux designed for the business man who is too tired to go home after the play… One might search the world and not find anything quite as unique or lavish as this midnight revue.”

The show was broken up into different comedy, singing, and dancing acts featuring stars like Frances White, Teddy Gerard, Eddie Cantor, Will Rogers, and W.C. Fields.

During the twenty-five minute intermission between the acts, audience members were welcome to dance, drink, and dine. For .75 cents to $1.00 (from $17-$23 today) guests could partake in a cold beer or soda, and for those willing to pay $2.75 ($64 today) there were small bottles of champagne readily available. The Ziegfeld kitchens were most known for their steak dinners, but also popular was Beluga caviar for $2.00 a serving ($47).

There was no limit to the extravagance of the Midnight Frolic, even after the US entered World War I. The New York Times reported in 1917 that, “For fear some one will think that he has adopted a policy of retrenchment because of the war Mr. Ziegfeld calls attention to one novelty, a chiffon scene in which the chiffon alone cost $3,000. He also wishes to state that the cost of production approximated $100,000.”

The club stayed open year-round for seven years and while World War I couldn’t stop the Midnight Frolic, Prohibition was ultimately what led Ziegfeld to end the show in 1922. He commented on this to the New York Times in 1921: “The best class of people from all over the world have been in the habit of coming up on the roof … and when they are subjected to the humiliation of having policemen stand by their tables and watch what they are drinking, then I do not care to keep open any longer… But occasionally some of my patrons have brought liquor of their own, and recently two men were arrested on the roof. When these things can happen I think it is time to close.”

That first midnight performance back in 1915 closes to a sea of hammers and cheers. You shuffle out with the crowd, your feet sore from dancing and the bright white lights of Broadway shining on your face. You feel tired, but you know there will be no way for you to fall asleep now after seeing the sensation of Ziegfeld’s Midnight Frolic.

Be sure to keep an eye out for photos like these and more with the IMLS Broadway Production Files digitization project.

![Byron Company. [James K. Hackett as Mercutio fights Campbell Gollan’s Tybalt] 1899. Museum of the City of New York. 34.271.813G](https://www.mcny.org/sites/default/files/styles/mcny_col_3_thumbnail/public/thumbnail_1.jpg?itok=eLop50mT)

![Lucas-Monroe. [Veronica Lake as Peter Pan and Lawrence Tibbett as Captain Hook], 1951. Museum of the City of New York. 80.104.1.2119](https://www.mcny.org/sites/default/files/styles/mcny_col_3_thumbnail/public/80_104_1_2119.jpg?itok=rvRZLxSK)