A View of Melrose

Tuesday, May 31, 2016 by

In November, 2016, the Museum of the City of New York will launch New York at Its Core, the first museum exhibition that comprehensively interprets and presents the story of New York City. Working on an exhibition can be detective work, whether searching for the perfect artifact to tell a story or uncovering the story behind an extraordinary object or image. As Project Assistant to New York at Its Core, over the past two years I have been thrown into dozens of sometimes unexpected research assignments—such as determining the exact location of this 19th century view of Melrose in the Bronx.

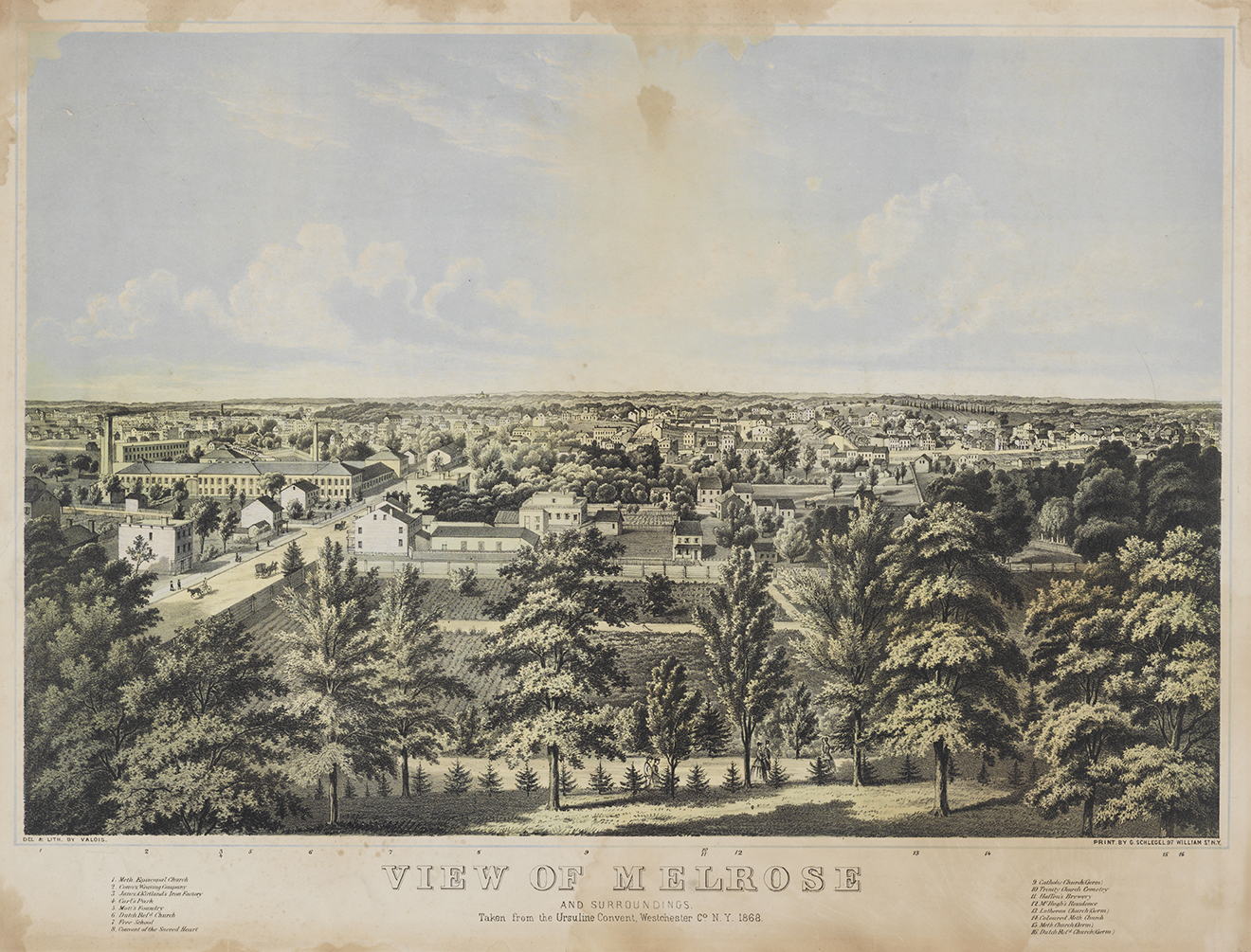

We had decided to use an 1868 lithograph of Melrose as one of seven immersive streetscapes projected on one wall of the gallery, representing the five boroughs from 1609 to 1898. We commissioned contemporary photographer Jeff Liao to recreate the views, giving visitors a window into how the city has changed over time.

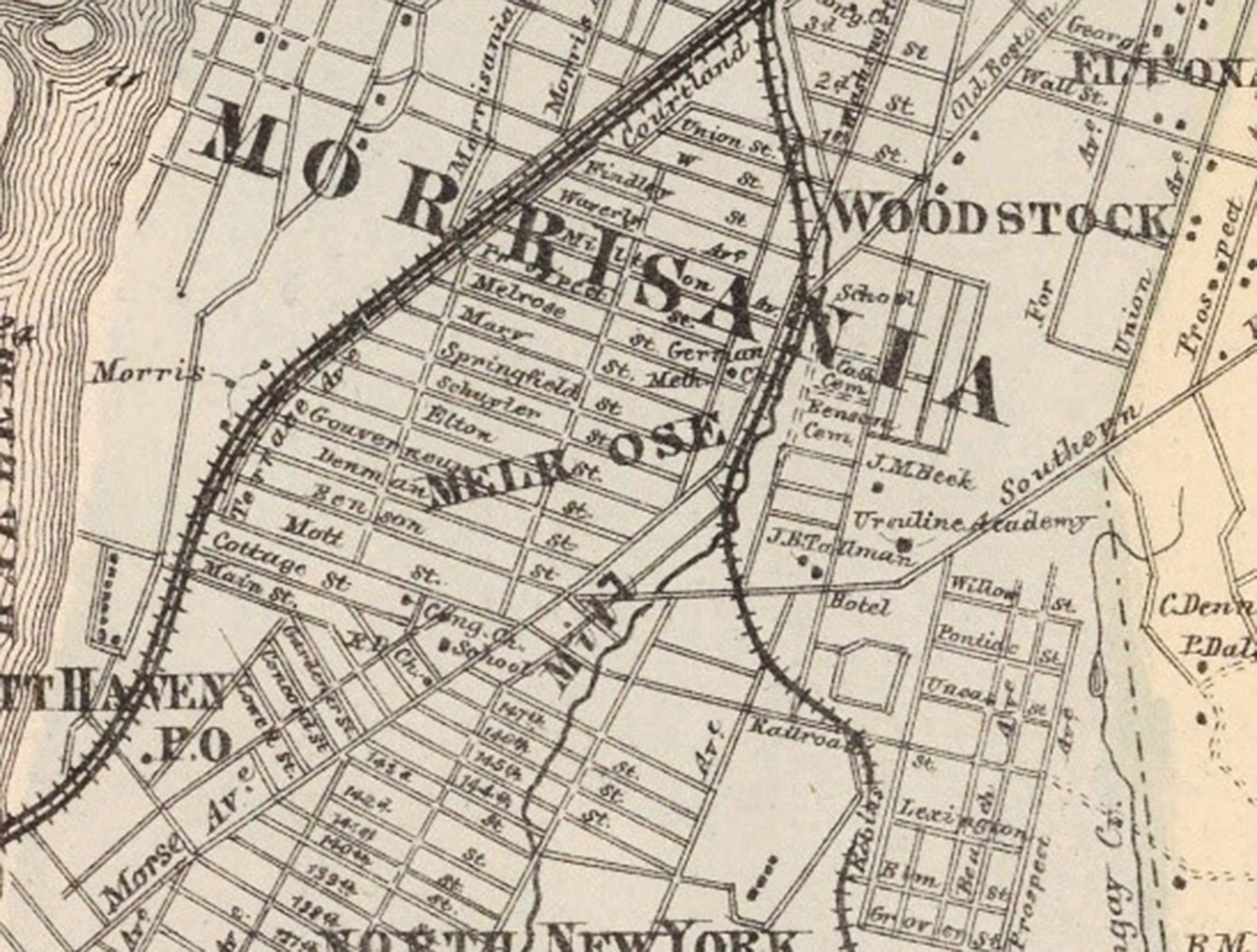

On a hot August afternoon last summer, I left the office early and caught the 5 train north. My objective was to locate the site of the Ursuline Convent in what had once been the rural village of Melrose, and was now the heart of the South Bronx. Unfortunately, the convent and school had moved to the Grand Concourse in the 1890s. Once I found the site, I had to figure out where, 148 years ago, a lithographer named Edward Valois had stood and sketched the village, then still part of Westchester County (the Bronx was incorporated into New York City in stages, beginning in 1874 and ending with consolidation in 1898.)

Earlier that week, I had searched dozens of historic maps before I found one that showed the convent. On the map, from 1867, many of Melrose’s streets are unchanged. However, the topography has been obliterated twice over—once at the turn of the century, when the convent’s rolling fields were replaced by crowded tenement apartments, then again in the 1950s, when urban renewal replaced the tenements with public housing. Which is how I found myself behind the parking lot of a housing project climbing a scraggly, weed-covered hill—all that remained, I surmised, of the hill on which the Ursuline nuns had built their convent in 1855. Unless it was just a pile of rubble, shoved to the side when the area was developed. Climbing out of the weeds, I realized how silly I had been. I didn’t need a hill, I needed a view. So what if the Ursuline Convent had been replaced by a housing tower? We just needed to get on the roof.

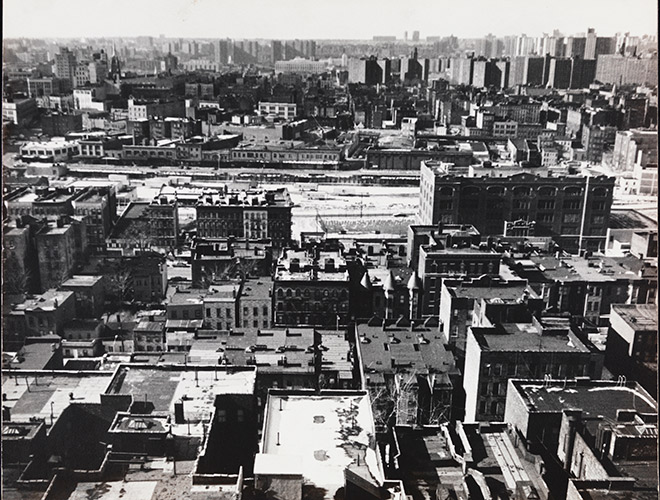

A few weeks and many phone calls later Jeff Liao, two videographers, the Building Manager and I gazed out over Melrose from the roof of the residential building. We were a little higher than a 19th century lithographer could have imagined, but it would do.

In order to recreate the lithograph we needed landmarks. Unfortunately, it appears that not a single building has survived in Melrose from 1868 to today. The train in the lithograph’s middle ground was one hint. The long-abandoned railroad tracks were lowered into an open cut below the streets in the early 20th century, but they still follow the same path. And while Westchester Avenue has been transformed by the elevated 2/5 train, its slightly off-kilter angle is unchanged.

Although the built environment of Melrose has been utterly transformed since 1868, View of Melrose is a remarkable record of continuity as well as change, documenting the relevance of New York at Its Core’s major themes—encapsulated in the keywords density, diversity, money and creativity—in the city’s history.

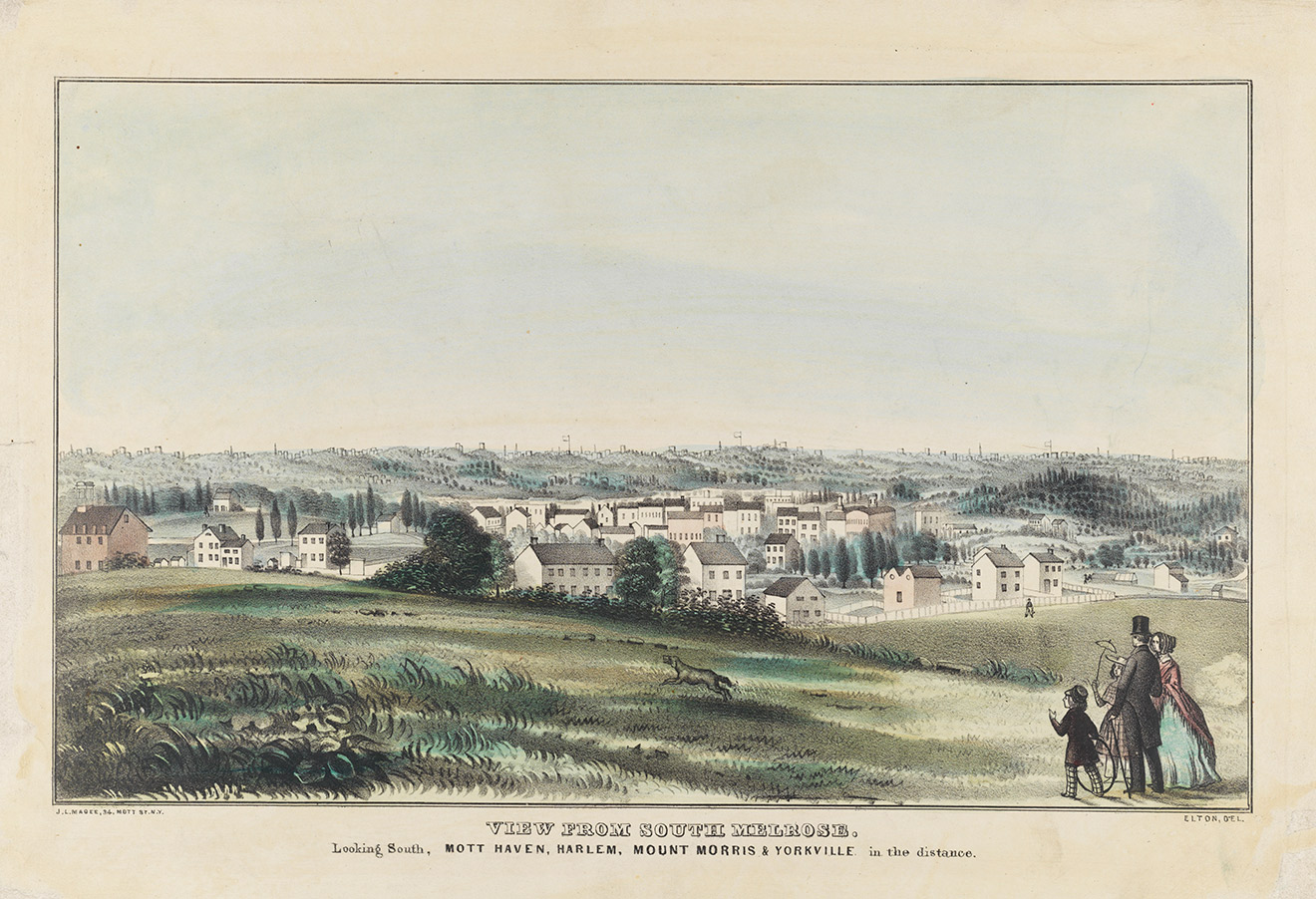

Beginning in the 1840s, an unprecedented wave of immigration transformed New York. By 1855, immigrants, mostly Irish and German, made up over half the city’s population, and many newly-arrived Germans fled crowded Manhattan to settle in Melrose.

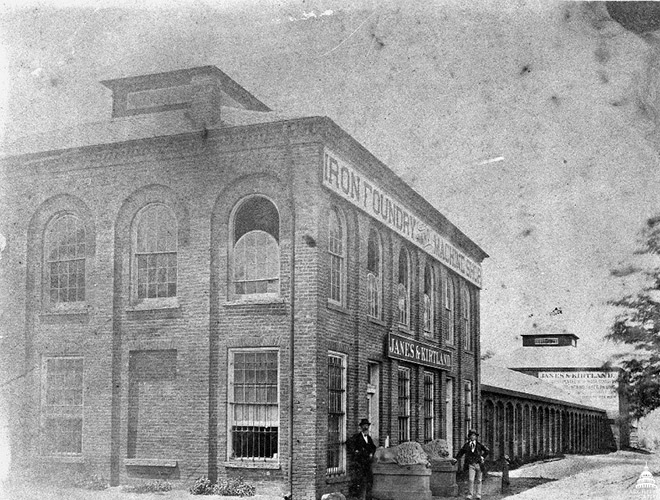

The 1840s also brought the aforementioned railroad, and with it a range of industries—iron works, breweries, textile mills—that shipped in raw materials and shipped out finished products, tying the diverse hamlet ever closer to New York’s booming port. In fact, when View of Melrose was printed, one of the Bronx’s most dramatic exports had just recently been completely at the Jans and Kirtland Iron Foundry, a prominent landmark on the lithograph’s far left: the cast-iron dome of the United States Capital, which was manufactured in Melrose and shipped in pieces to Washington.

The fortunes of any community inevitably ebb and flow. In the 1970s, the South Bronx became a national symbol of urban decline, ravaged by poverty, neglect, and fire. Remarkably, the City Museum has a photograph in its collection taken from the very same housing tower in 1971—a time when the neighborhood was much denser than it is today. Tenements and entire blocks of businesses have since been supplanted by grassy fields and row houses.

Despite its rural character, Melrose in 1867 was a community of immigrant entrepreneurs and thriving industry. Today, Melrose is once again a bustling residential neighborhood, home to a thriving central business district called the Hub, new construction, and a diverse population of Hispanic and African-American New Yorkers.

To see how this all came together, check out the video: