Vanderbilt Ball

How a costume ball changed New York elite society

Tuesday, August 6, 2013 by

In the spring of 1883, the solemnity of Lent didn’t stand a chance against the social event on the mind of all of New York’s elite society: Mrs. W. K. Vanderbilt’s fancy dress ball. The invitations had been hand delivered by servants in livery, young socialites had been practicing quadrilles (dances performed with four couples in a rectangular formation) for weeks, and “amid the rush and excitement of business, men have found their minds haunted by uncontrollable thoughts as to whether they should appear as Robert Le Diable, Cardinal Richelieu, Otho the Barbarian, or the Count of Monte Cristo, while the ladies have been driven to the verge of distraction in the effort to settle the comparative advantages of ancient, medieval, and modern costumes” (New York Times). The best dressmakers and cobblers had spent months poring over old books making costumes — which were already being breathlessly described by the New York Times — as historically accurate as possible.

Prior to the ball, Gilded Age New York society had been dominated by the Mrs. Astor. (Emphasis, hers – to even ask which Astor was a sure sign that you were thoroughly ignorant in the most basic points of New York’s social hierarchy.) Mrs. Caroline Schermerhorn Astor and self-appointed “society expert” Ward McAllister were the authorities in all things upper class. It was up to them to decide if your last name was venerable enough or if your bloodlines were pure enough for entry into the upper ranks of society. They were the champions of old money and tradition.

But New York’s social hierarchy is not known for being static. Thanks to the meteoric increase in millionaires in New York due to the Civil War and the Industrial Revolution, many of whose fortunes rivaled or even surpassed the oldest of families, Mrs. Astor and Ward McAllister had a whole new challenge in deciding who of the nouveau riche was acceptable. This led to the creation of the famous List of 400 — the Four Hundred people who were New York’s high society. One family that they deemed wholly unsuitable were the Vanderbilts. The willful crassness of Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt, the ambitious entrepreneurial shipping and railroad industry mogul, and patriarch of the family, was still the stuff of legends.

The Commodore’s grandson, William Kissam Vanderbilt, married the determined, pugilistic and socially ambitious Alva Erksine Smith from Mobile, Alabama (but schooled in Paris). Alva made it her mission to bring the Vanderbilts into what she thought was their proper place in society, and onto the list of the 400.

Her first move? Building an opulent French château style mansion designed by Richard Morris Hunt at 660 Fifth Avenue at 52nd street that literally overshadowed the dour, albeit luxurious, town homes that lined the avenue.

As grand as the mansion was, the ball which served as her housewarming party was even grander. On March 26, 1883 Alva threw one of the most incredible parties that New York had ever seen. With her access to seemingly endless amounts of money, she used every available resource – including the power of the press by inviting journalists to come in and preview the decorations before the ball began – to build excitement and to make it bigger than any ball before it. According to an apocryphal tale, Alva used what was possibly the simplest weapon in her arsenal to gain admission to the New York 400: good old fashioned manipulation. The story goes, that like all marriageable young girls Mrs. Astor’s daughter, Carrie, was anxiously awaiting her invitation and even began practicing for a quadrille with her friends. Then the unthinkable happened: all of her friends got their invitations and hers never came. She immediately got her mother on the case. Due to complex social customs, Alva claimed she could not invite Miss Astor since Mrs. Astor had never called on the Vanderbilt home. Mrs. Astor really had no choice but to drop her visiting card at 660 5th Avenue, thus formally acknowledging the Vanderbilts. The Astors’ invitation was received the next day.

At ten in the evening carriages began arriving at 660 5th Avenue, dropping off nearly 1200 outrageously costumed members of the highest ranks of society. Crowds, held back by police, strained to catch glimpses of debutantes and society stalwarts attired in their costumes as they were escorted into the mansion. Even Mrs. Astor (with her daughter) and Ward McAllister were there.

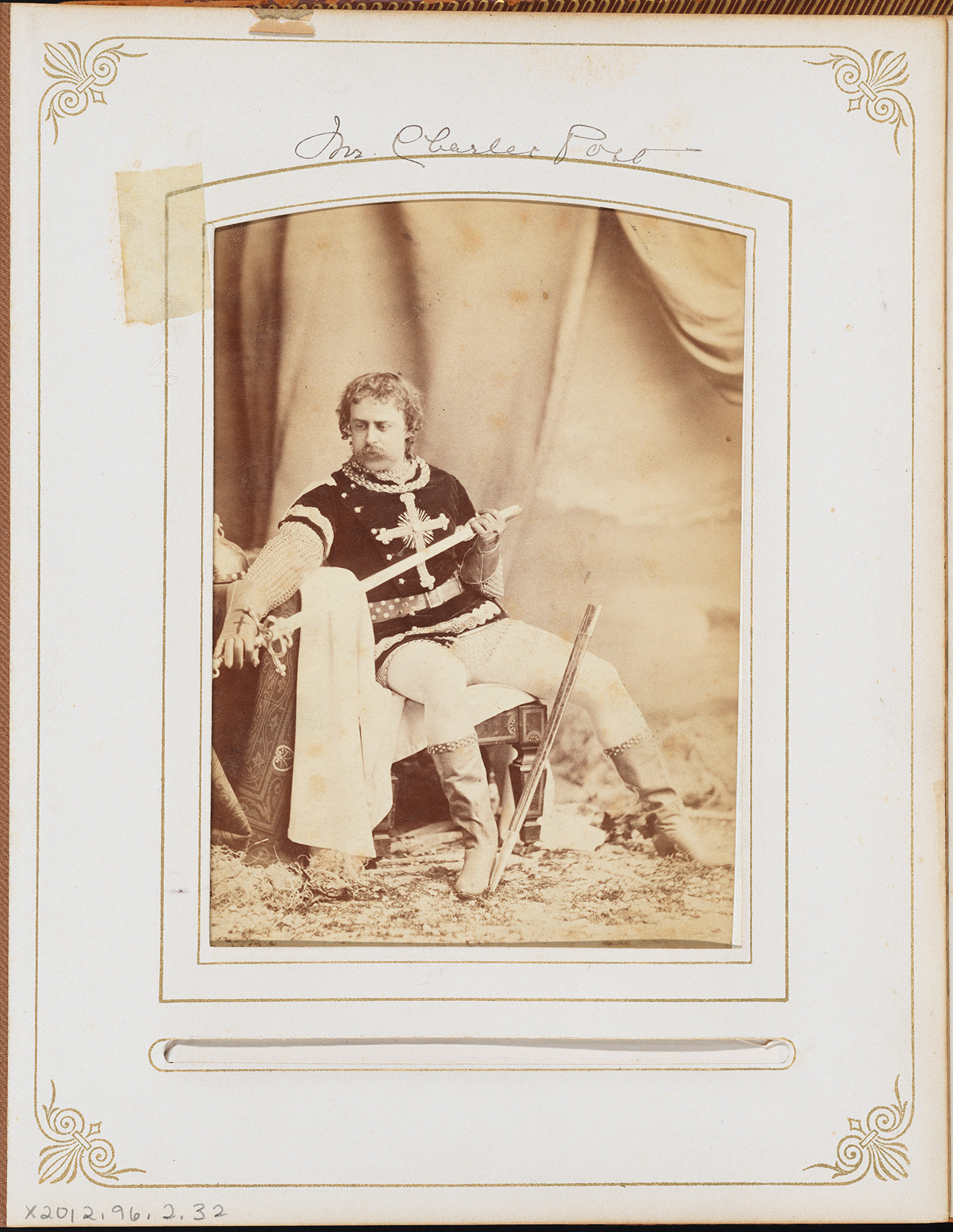

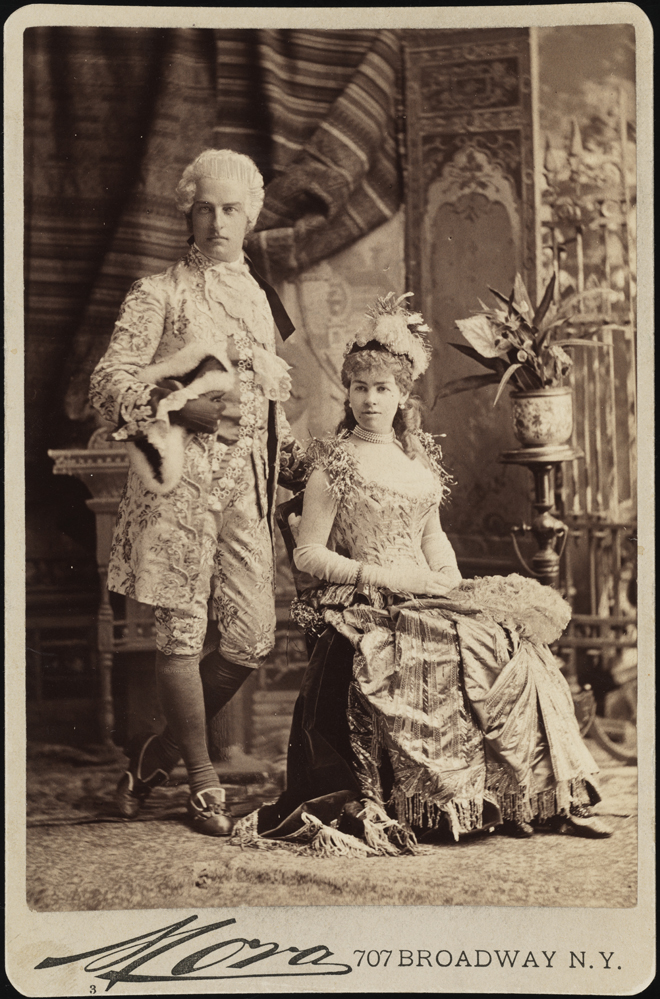

It is easy to see the casual display of over-the-top excess of the ball in these portraits of attendees in their costumes taken by Mora.

Miss Edith Fish was dressed as the Duchess of Burgundy, with real sapphires, rubies and emeralds studding the front of the dress.

One of the most amazing costumes was Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt II ‘s representation of “Electric Light” which even had a torch that lit up, thanks to batteries hidden in her dress. The dress is actually in the Museum’s costume collection and you can see it as it looked on Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt II in the cabinet card below, and how stunning it is in the full color collection image. (To take a closer look at the dress, visit our Worth/Mainbocher online exhibition here.)

At exactly 11:30 the ball began with the hobby-horse quadrille, the first of five quadrilles where the young people of society danced down the grand staircase in lavish costumes.

Dancers in the Dresden Quadrille wore all-white court costumes evoking the time of Frederick the Great and giving them the eerie and intentional look of living porcelain dolls.

For the Opera Bouffe quadrille, the costumes were just as elaborate. The New York Times described a dress as, “Miss Bessie Webb appeared as Mme. Le Diable in a red satin dress with a black velvet demon embroidered on it and the entire dress trimmed with demon fringe-that is to say, with a fringe ornamented with the heads and horns of little demons.” It’s not everyday that you hear the term “demon fringe”.

Speaking of things that you don’t hear or see on a daily basis, Miss Kate Fearing Strong wore a peculiar cat costume. Miss Strong, who Henry James described as “youthful and precocious,” went as her nickname “Puss”. Somewhat disturbingly, the entire costume consisted of a taxidermied cat head as seen in the image, but also seven cat tails sewn onto her skirt. Continuing with the animal theme, Alva’s sister-in-law went as a hornet, with an imported headdress made of diamonds.

After the last quadrille ended, the ball really began. Dozens of Louis XVIs, a King Lear “in his right mind”, Joan of Arc, Venetian noblewomen and hundreds of other costumed figures danced and drank among the flower filled house, including the third floor gymnasium that had been converted into a forest filled with palm trees and draped with bougainvillaeas and orchids. Dinner was served at 2 in the morning by the chefs of Delmonico’s working with the Vanderbilt’s small army of servants. The dancing continued until the sun was rising, diamonds and other jewels glinting in the changing light. Alva led her guests in one final Virginia reel and just like that, the ball was over. The fantasy world that Alva created turned back into reality as men in powdered wigs stumbled down Fifth Avenue, much to the amusement of children on their way to school.

Most contemporary sources put the cost of the ball at $250,000 (nearly 6 million dollars in today’s money), including such costs as $65,000 for champagne and $11,000 for flowers. It was conspicuous consumption at its finest and it worked. Newspapers across the country reported the most minute details and extolled Alva’s tastes and classiness. (This is not to say that there wasn’t a backlash to the ball. The New York Sun published this very stern article, critiquing the excess when there was so much suffering in the same city.). But as of March 27, 1883 the Vanderbilts were at the top of a new New York society that was not just limited to 400 people.

If you want to learn more about the Gilded Age in New York, come to the exhibition.