Thomas Nast takes down Tammany: A cartoonist’s crusade against a political boss

Tuesday, September 24, 2013 by

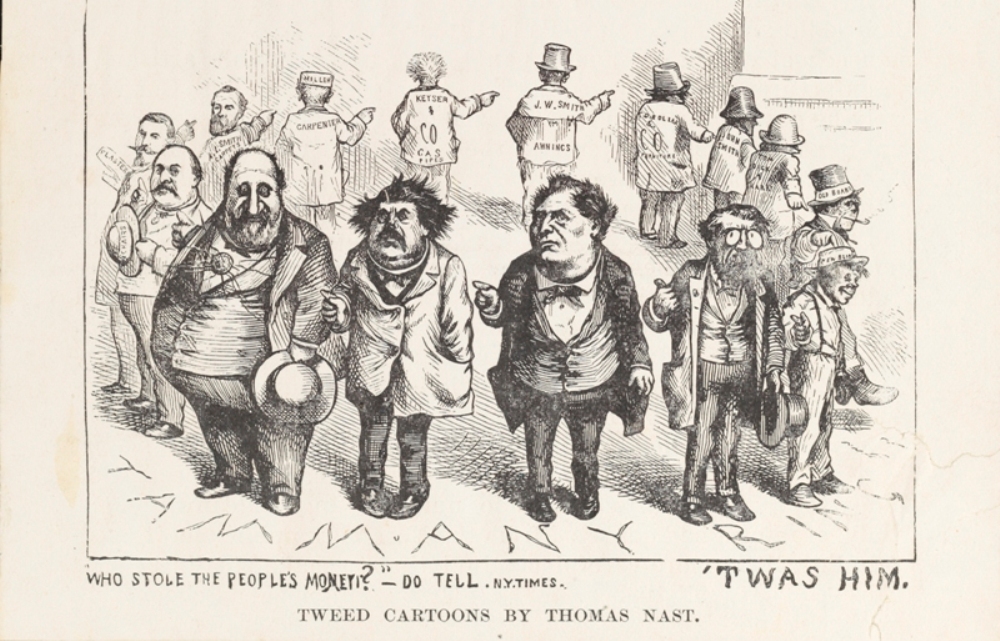

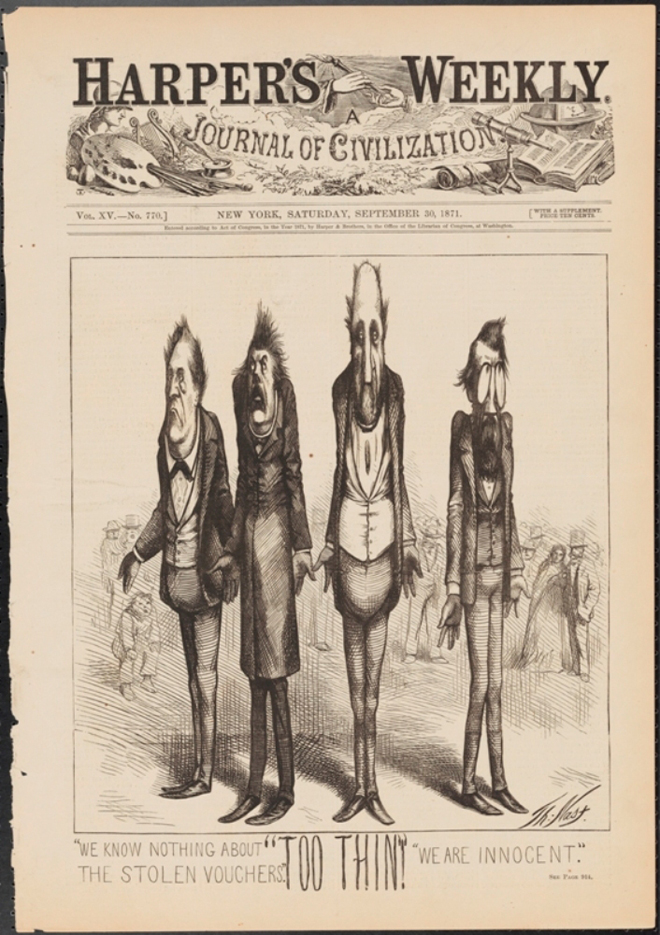

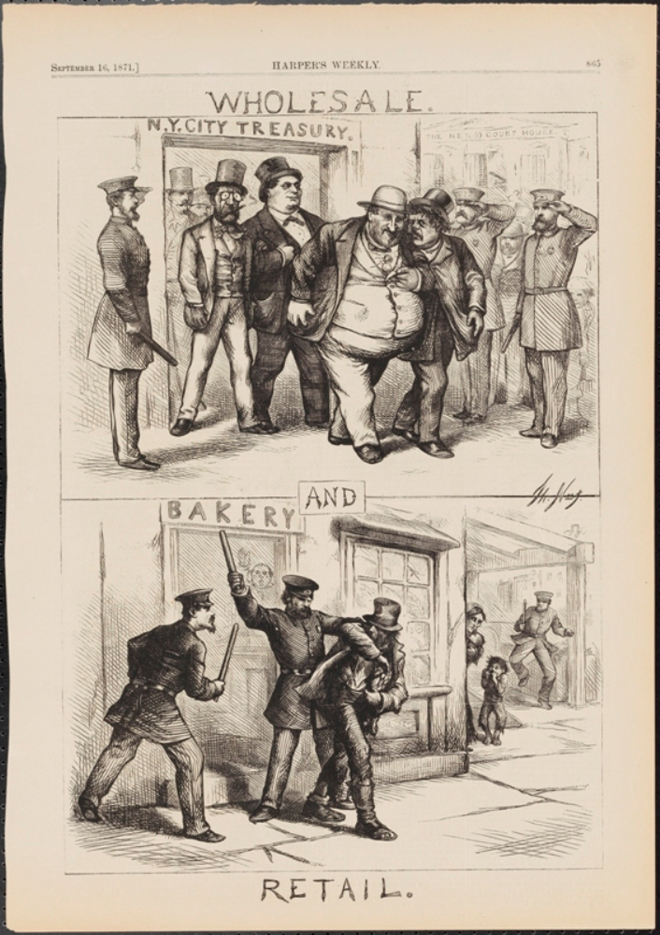

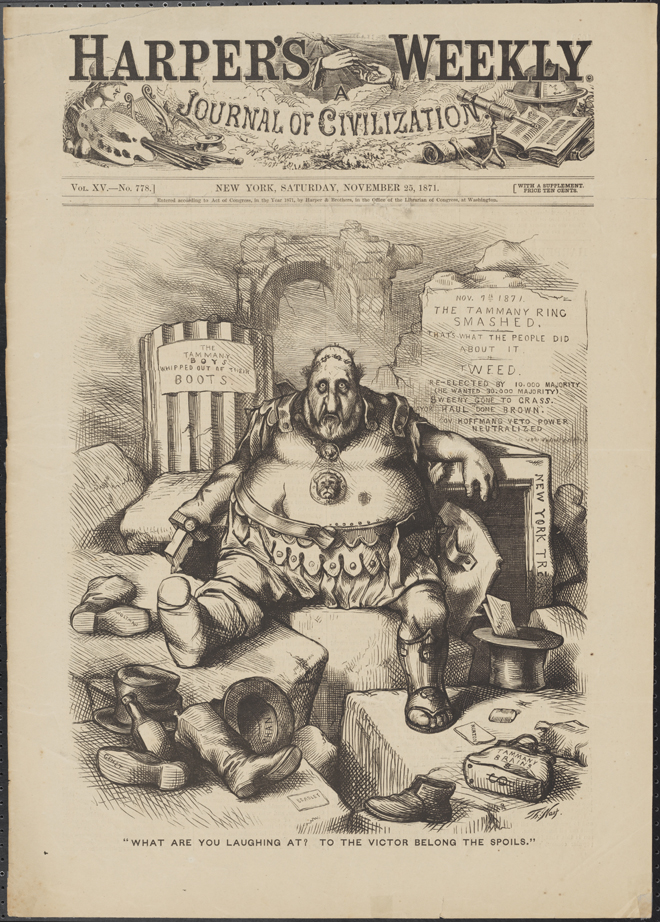

As the election cycle gets into full-swing, so do the pundits, journalists, and political cartoonists. While modern readers intrinsically link newspapers and political cartoons, the use of cartoons in the American media was minimal until Thomas Nast popularized them in the 1860s and 1870s. Known today as the father of American political cartoons, Nast gained fame as a cartoonist for Harper’s Magazine. Today he is best remembered for his cartoons about Boss Tweed and the Tammany Ring.

Tammany Hall was a New York City political organization that originated in the late 18th century. It became the Democratic Party’s political “machine” and thus controlled the party’s nominations. William M. Tweed, more commonly known as Boss Tweed, was a New York politician who became Tammany’s leader in the late 1860’s. As the party’s boss, he was able to appoint several city officials and essentially controlled the city government. As a result, he had access to an enormous amount of public money, which he used to enrich himself and his closest friends and allies through a variety of money laundering and profit sharing operations. It is estimated that he defrauded the city out of anywhere from $30 million to $200 million dollars (equivalent to $365 million to $2.4 billion today).

Tweed certainly had his supporters, including the large Irish immigrant population that made up his base. Under his lead, however, Tammany’s corruption was so vast and glaring – Tweed became known for wearing a large diamond in his shirtfront and lived in a mansion on Fifth Avenue – that he earned a wide range of critics. One of his most vocal critics was Thomas Nast, who featured Tweed and his cronies in many of his cartoons, particularly in 1870 and 1871.

Thomas Nast was a German immigrant who began his career illustrating newspapers and magazines, but eventually began creating political cartoons. Rising through the social and economic ranks, Nast embodied the American dream. He was a staunch advocate for municipal reform, and Tweed’s corruption fundamentally insulted his sense of equity.

![[William M. Tweed.] Sarony & Co., ca. 1869. Portrait Archive. Museum of the City of New York. 41.366.30](/sites/default/files/MNY303368.jpg)

Never afraid to take on issues of right and wrong, Nast became the scourge of Tweed and Tammany. His influence was so great primarily because of the visual nature of his work. Most of Tweed’s constituents were illiterate, so while they couldn’t read the scathing articles written about Tweed in The New York Times, they could understand Nast’s cartoons. Legend has it that Tweed was so threatened by Nast, he gave orders to “stop them damn pictures!”

In an attempt to “stop them damn pictures” Tweed sent a representative to Nast under the guise that a group of European benefactors wanted to offer him $100,000 (nearly $1.8 million today) to study art in Europe. Nast feigned interest and was able to increase the offer to $500,000, only to turn it down on the basis that he had long-ago made up his mind to put the Tweed ring behind bars.

Failing to bribe Nast, Tweed and his cronies went after Harper’s, threatening to have the Board of Elections boycott Harper’s textbooks, a significant financial threat. The board at Harper’s chose to support Nast, who created a series of cartoons depicting Tweed as a thief.

One can understand Tweed’s concern. Nast’s portrayal of Tweed as enormously bloated helped demonstrate the political leader’s corruption. His images captured public attention and helped incite public outrage. While he couldn’t force people to act or vote in a certain way, Nast influenced public opinion of Tweed and Tammany.

And the public responded. The 1871 election greatly weakened the Tweed Ring, with the public voting many Tammany candidates out of office, an event credited in part to Nast’s cartoons. While this had a huge impact on New York politics in general, it also pushed Nast to the forefront of his medium. He became the man who could topple political regimes.

Following the 1871 election, a host of fraud, forgery, and larceny charges were brought against Tweed and his allies. Many, including Tweed himself, were sent to prison. In 1875, however, Tweed escaped and set sail to Spain where he was eventually extradited after a Spanish officer recognized him from a Nast cartoon. Tweed was sent back to a New York jail, where he remained until his death in 1878.