Sophie Tucker: The Last of the Red Hot Mammas

Wednesday, November 15, 2017 by

Sophie Tucker was born Sonya Kalish on January 13, 1886, in Tulchin, Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. Several months after her birth, her family immigrated to the United States and later settled in Hartford, Connecticut.

Her parents opened a kosher restaurant and Tucker helped them out, first in the kitchen and later by waiting tables. She began singing songs as a waitress, much to the delight of customers, some of whom were Yiddish theater legends such as Jacob Adler and Bertha Kalich. In 1906, 20-year-old Tucker said goodbye to her family and departed for New York City, with dreams of becoming a big star.

Dearest Folks,

I have decided to go into show business. I have decided that I can do big things and have definitely made up my mind that you will never stand behind a stove and cook any more, and every comfort that I can bring you both I am going to do, and I know I can do it, if you will let me alone. Don’t come to take me back home. Take care of Son and I will make you proud of me some of these days.

Love to all,

Sophie

She rented a room on Second Avenue near St. Mark’s place for five dollars a week, which included breakfast. Her funds dwindling, it occurred to her that she could perhaps sing in neighborhood restaurants in exchange for a meal. Her first job was at Café Monopol on Eighth Street. She soon found gainful employment singing at the German Village beer garden on 40th Street near Broadway.

One day Tucker showed up at the 125th Street Theatre on the advice of the Tin Pan Alley music publishers, for Chris Brown’s amateur nights. After Tucker’s audition, Brown yelled to his assistant, “This one’s so big and ugly the crowd out front will razz her. Better get some cork and black her up. She’ll kill ‘em.”

Tucker took his hurtful comment in stride and sang three songs. As she recalled, “The three songs weren’t enough. The audience wouldn’t let me go till I had sung three more. Oh, they liked me all right. Take that, Mr. Chris Brown. I was a hit.”

Tucker began touring, performing in burnt cork make-up typically used by minstrel performers. By the early 20th century, performing in blackface was a well-accepted way to disguise a performer’s origins using dark makeup to cover the face and exaggerate the lips and eyes. Appearing in blackface makeup was the only way African Americans were allowed to perform on stage in many parts of the country. One night her trunk containing costumes and blackface makeup was misplaced. She appeared onstage anyway, telling the surprised audience, “You-all can see I’m a white girl. Well, I’ll tell you something more: I’m not Southern. […] I’m a Jewish girl, and I just learned this Southern accent doing a blackface act for two years. And now, Mr. Leader, please play my song.”

Once again, Tucker won over the audience. Before long she was performing out of blackface to increasing acclaim, including a coveted place on the Ziegfeld Follies of 1909 bill.

While on the Follies circuit, Tucker befriended a maid employed for Ziegfeld girl Lillian Lorraine. Her name was Mollie Elkins, and she had been a performer herself, for the Williams and Walker minstrel show on Broadway.

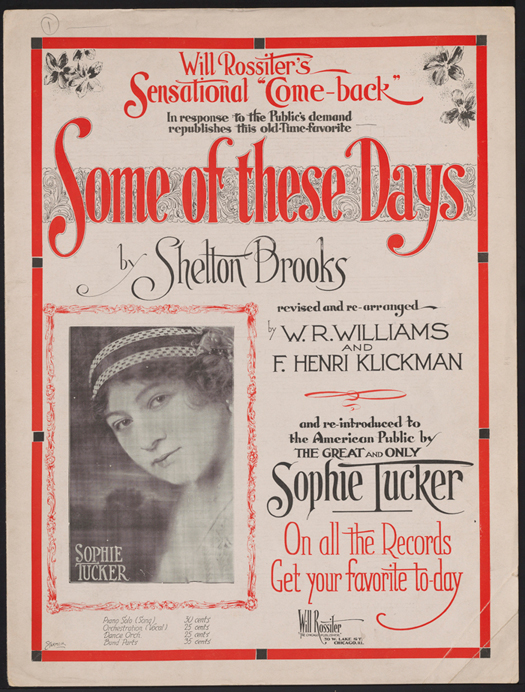

Elkins introduced Tucker to Shelton Brooks, who in 1910 composed the hit song Tucker became known for, “Some of These Days”.

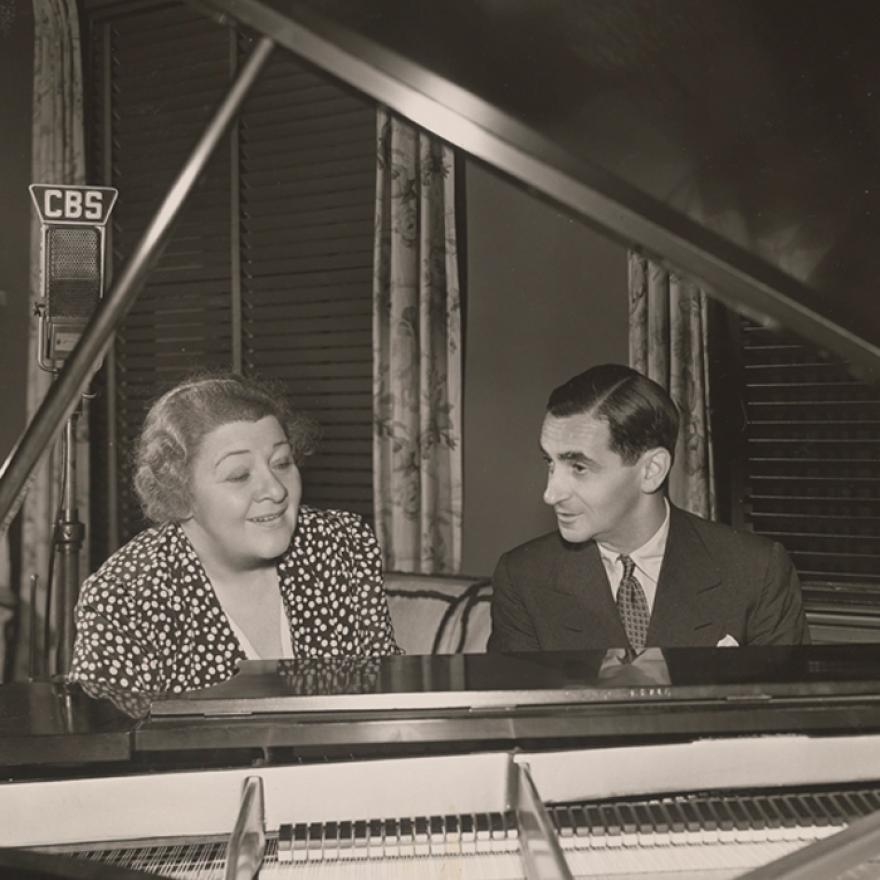

During the course of a career that spanned over fifty years, Tucker befriended and performed with people as larger than life as herself. She became known as “The Last of the Red Hot Mammas.”

Tucker continued to perform well into her seventies. In the early 1960s, she gave several Royal Command Performances before Queen Elizabeth which were well received.

Tucker died on February 9, 1966 at the age of 80, but her contributions to theater and comedy continue to have a lasting impact. To see more from the Sophie Tucker Collection, please visit the Collections Portal and the Sophie Tucker finding aid.

Photographs and sheet music in the collection were digitized and catalogued through a grant by the Atran Foundation.