Shirley Chisholm: Paving the Way for Kamala Harris

Wednesday, October 9, 2024 by

More than fifty years before Kamala Harris became the first Black woman and first Asian American nominee for president on a major party ticket, Shirley Chisholm became the first Black woman to seek the presidential nomination on a major party ticket. Chisholm, who was also the first Black woman in Congress, became the only Black woman to bring delegates to a convention until the Democratic National Convention in August 2024. Chisholm’s pioneering campaign, background, and the policy issues she raised in her historic political career provided a path for Harris’s own historic campaign.

Like Vice President Harris, Chisholm was the child of immigrants that included Caribbean heritage: Harris’s parents are from India and Jamaica, Chisholm’s were from Barbados and Guyana. While Harris grew up in Oakland, California, home of a longstanding Black activist community, Chisholm grew up in the Black and Caribbean diaspora of New York City, living for several years as a child in Barbados and then returning to Brooklyn. Chisholm’s diasporic experience and her race, gender, and class propelled not only how she saw herself, but the work she did while in office.

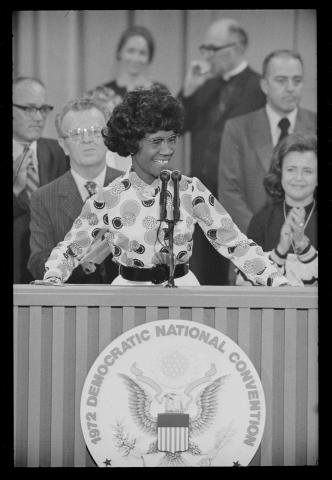

Chisholm viewed working within the political system as a way to make change. While she never served in local office, as like Harris did as DA of San Francisco, Chisholm’s was elected to both state and national office. She won a seat in the New York State Assembly in 1964, and in 1968 beat out many opponents to become the first Black woman in Congress. She had been there for just four years (like Harris), when she ran for President. At a tumultuous moment shaped by war, social movements, and a controversial incumbent candidate, Chisholm sought to rally a diverse coalition of young people, people of color, women, LGBTQIA+ folks, and other marginalized groups. While she campaigned in 11 states and won 2.7% of the vote nationwide, she remained the only Black woman to bring delegates all the way to a convention until the Democratic National Convention of 2024.

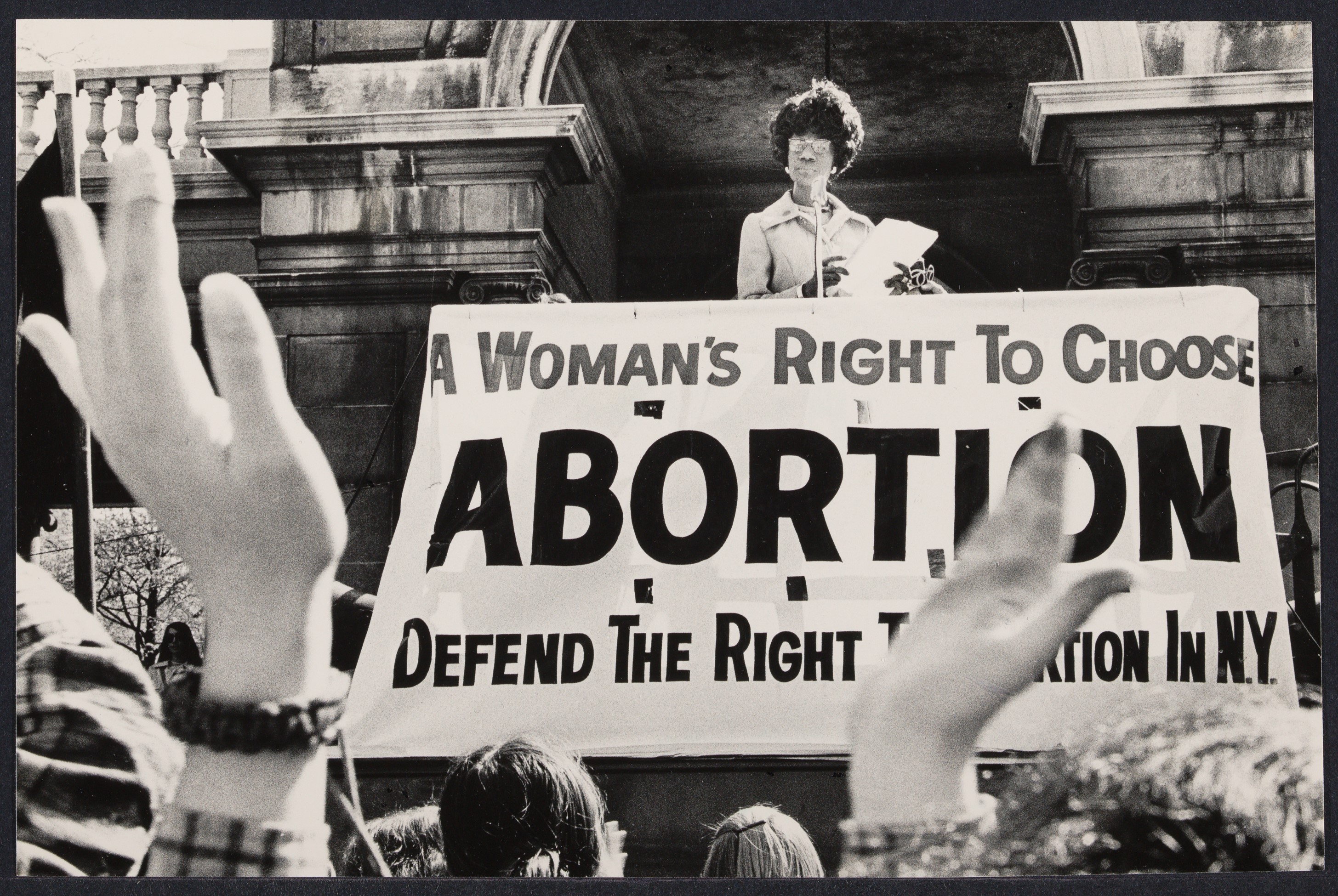

The issues that informed Chisholm’s campaign continue to resonate in Harris’s more than a half a century later. Foremost among those is reproductive freedom. Before, during, and after her presidential run, Chisholm championed access to abortion. Amidst political backlash from some activists who emphasized histories of sterilization of Black women, Chisholm consistently framed abortion as a medical issue and one of reproductive justice for women of color. She worked with NOW-NY on abortion rights in New York State in 1966, served as honorary chair of NARAL in 1969, and introduced congressional legislation that stalled until the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade in 1973. Chisholm remained a staunch advocate for abortion access as subsequent generations mobilized around reproductive justice for Black women, including Harris.

Education is another issue that links Chisholm and Harris, and in particular the practice of busing as a way to integrate schools. While Chisholm supported community control of New York City schools in the late 1960s as one path to quality education for Black students, she was also open to busing to facilitate interactions across racial lines. Kamala Harris also spoke pointedly about busing, when she criticized Joe Biden during a presidential debate in 2020 for his opposition to busing alongside white Democrat segregationists. Harris shared her personal experience, recounting “There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day. And that little girl was me."

The school-related issue that Chisholm championed most was early childhood education. Chisholm worked as a teacher and administrator in early childhood programs before entering elected office. In the Assembly she co-founded the SEEK (the Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge) Program with the City University of New York to create pathways to higher education for underrepresented communities. In Congress she fought for the Comprehensive Child Development Act, a bill for a subsidized national day care system that passed both houses only to be vetoed by President Nixon in 1971. Although Chisholm did not have children—a point of scrutiny for candidates then and now—she viewed childcare for impoverished and working women as an issue at the crux of race, gender, and class. Although a national early childhood program remains elusive, in February 2024 Vice President Kamala Harris announced caps to childcare costs for families who qualify for subsidized childcare and chose former teacher Tim Walz as a running mate.

Despite common threads that run through both of their careers, undoubtedly Chisholm and Harris would have divergences too. As a District Attorney and Attorney General, Harris’s position has evolved on police conduct and oversight. From her time in the New York State Assembly, Chisholm sought police reform by proposing mandatory civil rights training for police officers. She was also one of two elected officials trusted by Attica Prison inmates to visit and negotiate with prison officials during their uprising in 1971 and had similarly advocated reform for incarcerated New Yorkers after a riot at the Queens House of Detention the previous year.

In her memoir released after the 1972 race, The Good Fight, Chisholm explains her campaign for President: “I ran because someone had to do it first. In this country everybody is supposed to be able to run for President, but that’s never been really true.” In the face of constant questioning about her candidacy’s seriousness, she asserted, for those who came next, “the door is not open yet, but it is ajar.”

At the end of her life, Chisholm maintained that she wanted to be remembered not solely as a first, but as someone who fought for change in her time. Harris picked up on both sentiments when she won her historic bid for Vice President in 2020 and tweeted “Today, I'm thinking about her inspirational words: ‘I am, and always will be a catalyst for change.’” As Harris seeks change through her bid for the nation’s highest office on November 5th—the same month that ends with Chisholm’s centennial birthday on the 30th—we must recognize how the work of Shirley Chisholm helped make this campaign possible.

Sarah J. Seidman is a historian and Puffin Foundation Curator of Social Activism at the Museum of the City of New York and co-curator, with Dr. Zinga A. Fraser, Director of the Shirley Chisholm Project at Brooklyn College, of Changing the Face of Democracy: Shirley Chisholm at 100, on view at the Museum of the City of New York through July 2025.