Resuscitating Ruby’s Dolls

Monday, April 17, 2017 by

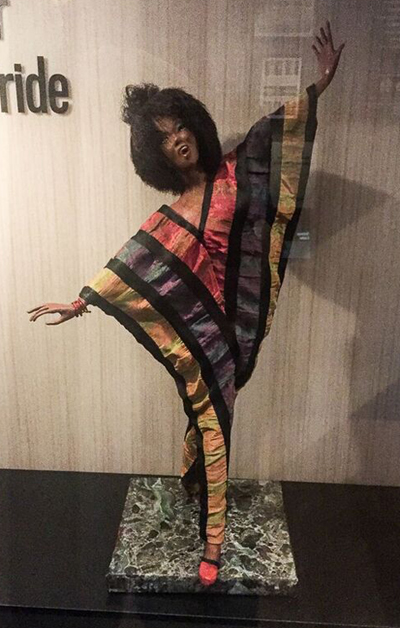

During the early brainstorming sessions for New York at Its Core, discussions turned to the potential exhibition of Bermuda-born New York designer Ruby Bailey’s “Cotton Sculpture” dolls. In 2004, the Museum accepted the 29 fashion “Manikins” into its collection, despite the fact the objects' condition had deteriorated in the years leading up to their accession by the Museum. Ruby's dolls are not only unique representations of animation and balance, but they provide compelling insights into her inspired creative vision at a time when the “Black is Beautiful” ethos ignited her 1960s Harlem community.

In the interest of responsible stewardship and in order to prepare Ruby's dolls for exhibition, the Curator of Costumes and Textiles sought out the wisdom of expert museum object conservators. The professionals would need to take into account both methods of stabilization that typically relate to the treatment and preservation of ethnographic objects, as well as treatment that produces a satisfactory visual result for public exhibition in New York at Its Core. Conservator Steve Weintraub of Art Preservation Services identified ethical and aesthetic issues as key factors when developing a custom conservation plan appropriate for the Ruby Bailey dolls’ singular problems. The Museum needed to strike a balance between presentation, integrity, reversibility, and artist's intention in treatment, using methods consistent with conservation field standards to stabilize the object while maintaining the artist’s original vision.

In keeping with this goal, Chris Piazza, a gifted sculptor whose singular works incorporate materials and techniques that closely parallel those used in the dolls’ fabrication, was chosen to structurally reinforce, and in some cases restore elements missing from the bodies of the first four dolls prepared for the exhibition.

The couture garments worn by each, here referred to as “Dancer,” “Harem,” “From Sea to Shining Sea” (artist’s name), and “Boa” snakeskin ensemble, were painstakingly vacuumed and stabilized by textile conservator Valerie Boisseau Tulloch, in efforts to return Ruby’s “Manikins” to their former glory. The collaborative work of multiple conservators has enhanced the range of story-telling of these objects, and provides unique perspectives on New York creativity that play within New York at Its Core.

Conservation by Chris Piazza

My own experience as an artist informed my approach towards the restoration of the dolls. My work is similar to Ruby’s in that I make figures involving the use of direct sculpture, fabric, and found materials. I incorporate vintage and antique materials that require the use of archival methods, particularly regarding adhesives and structural issues. Accordingly, I was familiar with some of the challenges Ruby dealt with in making the dolls, and many of the techniques she used.

The most significant consideration in the restorative work was the preservation of Ruby’s own vision. My task was to stabilize the dolls structurally while retaining every creative step and aspect of Ruby’s process. This required a thorough examination of the dolls, identifying materials and techniques she used as well as decisions she may have made in construction. Based on her own accounts, Ruby’s “cotton sculpture“ relied upon a modeling medium she created by boiling together raw cotton fiber and glue. Despite my research efforts, I was unable to turn up more specific information, as Ruby failed to document the exact details of her process.

One primary point of concern was that although Ruby brought great care to sculpting the faces and hands, she was less focused on the crowns of the doll’s heads, which were casually fabricated with little attention to finishing the surfaces. The wigs had been glued here, so in Ruby’s thinking, it seemed less important to finish these areas with the same care. These areas were often thin enough to break under the slightest pressure. She also casually left basting thread in place as well as straight pins that still remained as anchors for wigs and costumes.

I tried to identify other signature details to better understand Ruby’s working approach and her influences. This was particularly important in my work to repair portions of the dolls that were entirely missing and required interpretive resolution. The hands of “The Dancer”, for example, were missing their fingers.

All that remained of one hand was the palm and thumb. It was critical to identify what might have inspired her as an active participant in Harlem’s cultural scene in order to re-create their original expressive gesture. I studied the movements of dancer/choreographer Katherine Dunham.

Another instance where this issue was of great importance was in replacing the dolls’ hair. The original human hair wigs were greatly deteriorated, and I had to decipher Ruby’s intention from what remained. I studied The Grandassa Models and Elombe Brath and Kwame Brathwaite’s “Naturally” shows which energized the community through their “Black is Beautiful” movement.

As a Harlem resident and community activist, Ruby was likely aware of this and the annual fashion shows. That influence, along with the many popular black female entertainers at the time, seems apparent in her work. Artists such as Abbey Lincoln, Nina Simone, Ronnie Spector, The Supremes, and Dionne Warwick were additional possible influences which I kept in mind when creating the new hairpieces.

The video below provides an additional behind-the-scenes look at the elaborate process of conserving these truly unique objects.