New York Schools and Integration, Revisited

Thursday, September 6, 2018 by

As we lament the end of summer and greet the first days of the school year, we are reminded of the past, present, and future of one of the thorniest topics facing the city: how we educate our children, and how our schools do – and don’t – reflect New York City’s hallmark diversity. The long history and persistent challenges of school segregation are addressed in multiple exhibitions at the Museum, including the World City and Future City Lab galleries of New York at its Core, as well as in Activist New York. In honor of back-to-school week, we are revisiting this history and considering what, if anything, should be done to address the issue.

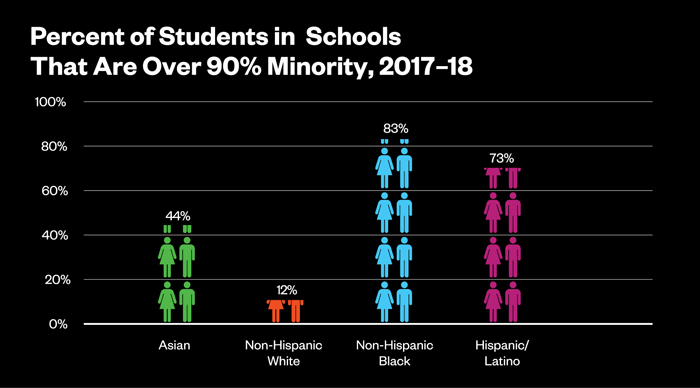

New York City’s public school system, the largest in the nation with 1.1 million students enrolled in over 1,700 schools, is also one of the most racially segregated, with 83% of black students and 73% of Hispanic students attending schools that are less than 10% white (as compared to 12% of white students and 44% of Asian students). This cannot be explained by residential patterns alone, as schools are considerably more segregated than neighborhoods.

Given that education is one of the principal drivers of economic mobility in the United States, critics argue that school segregation perpetuates and exacerbates racial inequality, with higher-quality schools often located in more affluent, whiter neighborhoods and lower-performing schools overwhelmingly located in low-income communities of color. In addition to depriving poor children of educational resources, segregation also denies students of all classes the opportunity to interact with people of all races and cultural backgrounds. Studies have demonstrated that most students, regardless of race, benefit socially and academically from being in racially integrated school environments.

Nevertheless, there is a great deal of debate as to whether the Department of Education should be more actively involved in seeking to integrate public schools. Some parents and policy analysts believe that parents and students should be the ones making decisions as to where children attend school, and that the government should not be in the business of trying to engineer the racial dynamics of school attendance. Others feel that this position ignores the barriers that low-income families face in making such decisions as well as the structural disparities, often exacerbated by government policies, which have caused segregation in the first place. Some people also believe that the focus on racial integration is misplaced, in that there is nothing inherently beneficial about students of color being in classrooms with more white students, arguing that what is really needed is for majority-minority schools to be provided with greater autonomy and access to similar resources as majority-white schools.

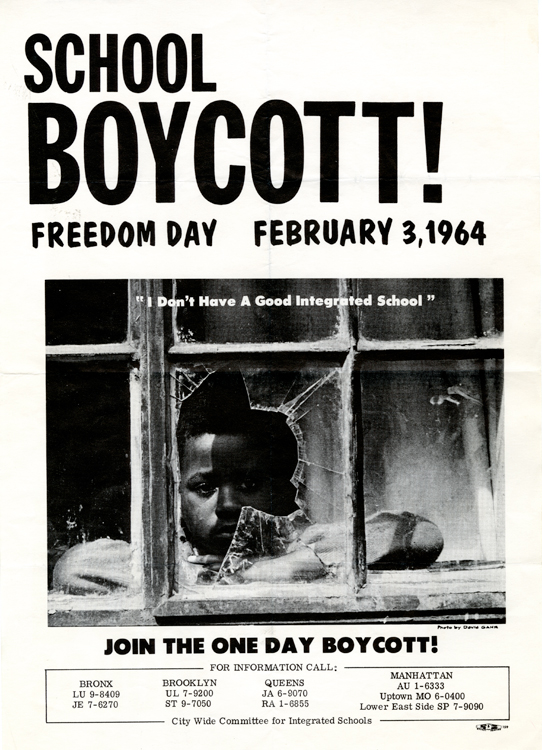

These debates are not new. On February 3, 1964, over 400,000 elementary school students stayed home to call on the Board of Education to outline and implement a plan for more integrated schools. Another boycott on March 16 drew 250,000 students. Education activists such as the Brooklyn-based Reverend Milton Galamison had spent years working with parents and community organizations to push for change, but the Board of Education did not respond with a plan. Galamison turned instead towards community control of public schools to advocate for greater roles for parents of students of color. Conflict over the community control debate, and who should determine the policies and practices of public schooling, helped lead to an acrimonious teachers’ strike in 1968.

Today, New Yorkers continue to debate what, if anything, the city can and should do to address school segregation. Some have sought to remake the racial profile of schools. But imposing racial quotas on public schools is unconstitutional, and Mayor Bill DeBlasio has for some time argued that, given that most children attend schools close to home, school segregation is largely a function of where people live, and therefore is not an issue that they can easily solve. While residential segregation certainly contributes to the issue, school segregation is further amplified by factors such as demographic sorting among middle and high schools, which can select students based on academic performance, and the fact that wealthier families have more options – sending their children to private schools in some cases, or in other cases sending children to better schools that are farther away, which comes with additional opportunity costs and transportation costs.

More recently, with the appointment of New York City Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza in April 2018 and the push to change the admissions policy for the city’s elite specialized high schools, Mayor DeBlasio has revisited this issue. Other advocates for desegregation have focused on economic status rather than race, proposing applying a “controlled choice” approach for high schools and middle schools across the city, in which a certain percentage of seats in high-performing schools are reserved for low-income students. Controlled choice is currently an optional program adopted by select schools, often at the behest of parents as opposed to a mandate from the Department of Education.

Another approach that was just recently adopted by District 15 in Brooklyn, largely due to parental advocacy, is to eliminate the existing competitive middle school admission process, which relies on testing, and replace it with a lottery system. Some people argue that such grassroots efforts may be more effective than imposing income quotas, in that they generate less backlash and can be tailored to the needs of individual communities. But it is uncertain whether such voluntary efforts will be enough to make a large difference in educational outcomes citywide. For elementary schools, the challenge is a little more daunting, since most students attend their zoned school, but segregation could be addressed through rezoning and other efforts.

None of these approaches are easy, and all of them are likely to face resistance on the part of some parents who are concerned about impacts on their neighborhoods and their children’s education. It is also likely that in order for school integration efforts to be truly effective they must be part of larger efforts to address other structural inequities in housing and employment. But clear, feasible approaches to mitigating this problem exist, and the cost of doing nothing is the perpetuation of a system that exacerbates inequality and exclusion. What seems certain is that New Yorkers will be grappling with this complex issue for years, if not decades, to come. What do you think should be done to address school segregation?

Learn more about segregation and integration in New York City’s schools and neighborhoods in the Future City Lab and Activist New York exhibitions at the Museum.