The New Colossus

Thursday, February 16, 2017 by

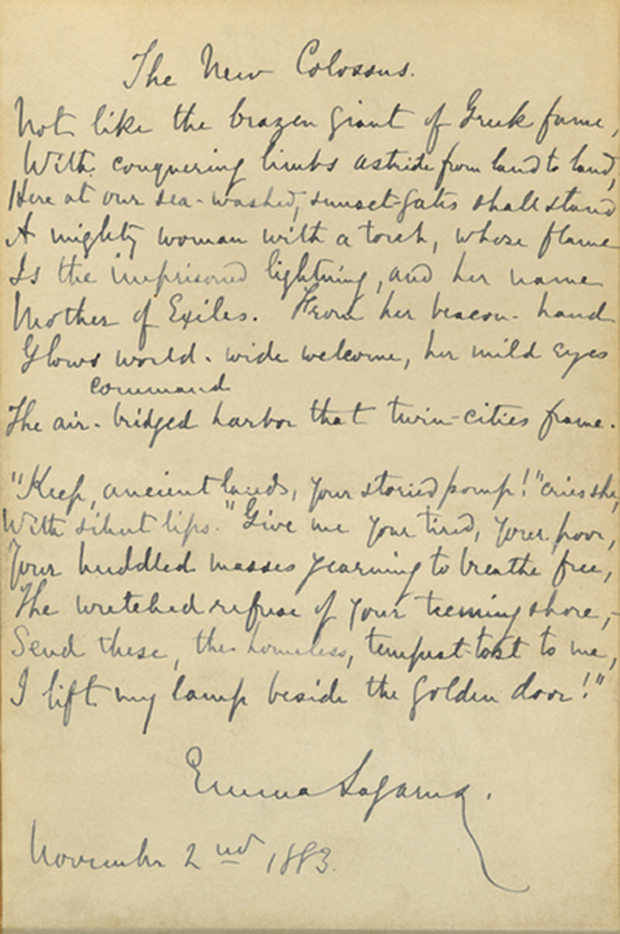

On view* in the Museum of the City of New York’s landmark exhibition New York at Its Core is a small manuscript in black ink; the script is messy and the signature is hard to make out, but the words are familiar to Americans young and old. They have appeared recently on protest signs from New York to Washington, D.C. In fact, many of us can recite the words by heart:

“

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free

They are the words inscribed on a plaque at the Statue of Liberty. For many, these words are proof that welcoming immigrants and refugees is as fundamental to what it means to be American as the idea of “liberty” itself.

The statue, a gift to America from the people of France, was unveiled in 1886 but it was not until 1903 that these words, written 20 years earlier by a then well-known New York poet, became part of the Statue of Liberty. It would take even longer for the meanings of the words and the statue to become completely intertwined.

The Statue of Liberty is an allegorical sculpture. Popular in the Gilded Age through the turn of the century, allegorical sculptures are meant to personify abstract ideas. Think of the image of “Justice” – a blindfolded woman holding scales in one hand and a sword in the other. Another example is the group of allegorical figures on top of Grand Central Terminal from 1912. In this case three figures representing strength (in the form of the Greek god Hercules), speed (Mercury), and wisdom (Minerva) are meant to represent the idea of “Transportation” when taken together.

The statue’s original name, “Liberty Enlightening the World” gives us an idea of what the project’s French backer, political thinker Édouard René Lefèbvre de Laboulaye, and his sculptor, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, intended the sculpture to personify. Not just “liberty” itself, but also the idea that American “liberty” is a shining light guiding the whole world from the harbor of the young democracy’s largest city.

In 1875 Laboulaye formally announced the gift and set up an agreement in which the French people would contribute to the cost of construction of the sculpture, while the American people (rather than the government) would pay for the statue’s pedestal.

Fundraising for the pedestal was difficult. To build up excitement, parts of the statue appeared in various exhibitions and in public places. Committees were formed, meetings were held, and figurines of the statue were sold. It would take ten years and the intervention of publisher Joseph Pulitzer, who printed the name of every single contributor in his fledgling paper the World, no matter how small the donation, to raise the amount needed to realize a pedestal designed by Richard Morris Hunt. (Pulitzer, the true hero of the pedestal, raised $100,000 in donations ranging from 5c to $250 between March and August of 1885, in the process increasing his paper’s circulation, and adding an image of the statue to its masthead.)

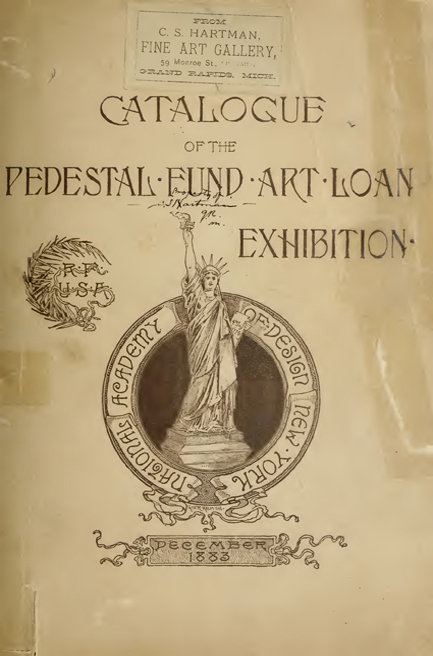

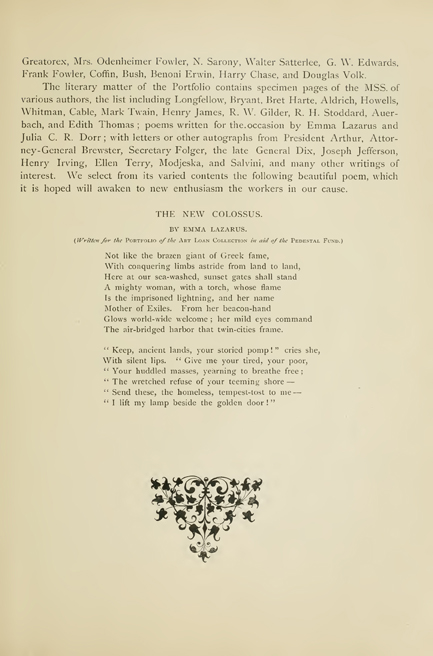

In December of 1883 an Art Loan Exhibition was held at New York’s Academy of Design to help raise money for the pedestal. The exhibition and auction featured fine art, lace, stained glass, armor, and antique furniture, as well as literary manuscripts. According to The New York Times nearly 1,500 people attended the formal opening. After a choir sang “Hymn to Liberty,” the exhibition’s director, Mr. F. Hopkinson Smith, read a sonnet written for the exhibition catalog by a poet named Emma Lazarus called “The New Colossus.” Those who attended would have heard the statue called, not so much a beacon of liberty for the whole world, but

“

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame is the imprisoned lightening, and her name Mother of Exiles.

”

Lazarus was not a surprising choice to contribute to the auction; she was a frequent contributor to literary magazines, had published several books, and belonged to literary circles that included Ralph Waldo Emmerson. Her contribution to the Art Loan Exhibition catalog was one of two poems written expressly for the occasion (the other was by the now largely forgotten American poet Julia C. R. Dorr), but manuscripts by Longfellow, Mark Twain, and Henry James were also included in the auction.

The daughter of sugar refiner Moses Lazarus, Emma was also a member of New York’s Jewish social elite. Her great uncle, Moses Mendes Seixas, had known George Washington; she counted Georgina Schuyler, a direct descendant of Alexander Hamilton, as a friend; and her first cousin, Benjamin Cardozo, eventually served on the Supreme Court. In fact, her family could trace its roots back to the first Jewish settlers in New York, a group of 23 Sephardic Jewish refugees who arrived in New York in 1654, after fleeing the Portuguese takeover of the Dutch colony in what is now Brazil.

Yet it was a more immediate Jewish refugee crisis that most likely inspired her to find a “Mother of Exiles” in what was supposed to be a “Statue of Liberty.” The Russian pogroms of the early 1880s and the flood of poor Russian Jewish immigrants and refugees arriving in New York inspired Lazarus to start working with the Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society, volunteering as an aide to newly arrived immigrants at Ward’s Island, and to help establish the Hebrew Technical Institute. She began exploring Jewish themes in her poetry as well.

The American Romantic poet James Russell Lowell wrote to Lazarus a few days after the opening of the Art Loan Exhibition saying, “your sonnet gives its subject a raison d’être which it wanted before quite as much as it wants a pedestal. You have set it on a noble one, saying admirably just the right word to be said.” He credited her with “an achievement more arduous than that of the sculptor.”

Yet that particular “raison d’être” would remain quietly buried in the obscure exhibition catalog for the next several years. Although the World published the poem after the exhibition, the Times did not. No public mention was made of the poem at the statue’s dedication in 1886. In fact, Lazarus was in Europe when the statue was unveiled, and she died, likely from Hodgkin’s disease, shortly after her return in 1887. Her warm obituaries do not mention “The New Colossus” either. It was Lazarus’s friend, Georgina Schuyler, who reunited the words and the statue in 1903. In honor of her friend, she had a plaque inscribed with the poem installed inside the statue’s base. It was then that The New York Times published the poem for the first time, as did the New-York Daily Tribune.

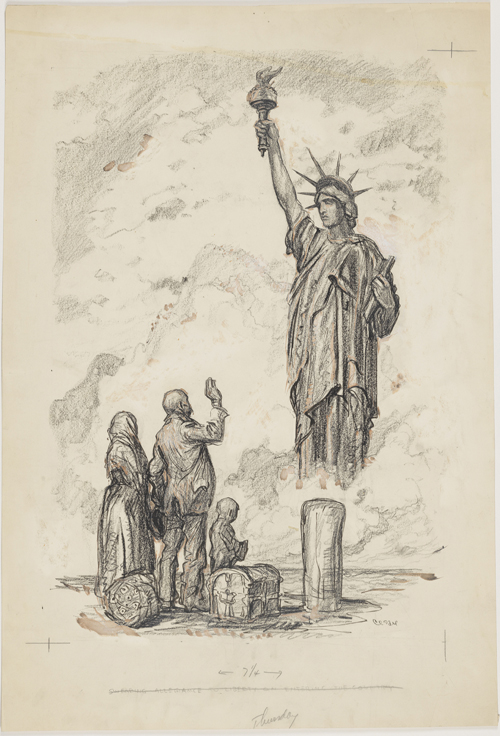

Lazarus’s interpretation of the statue, a subtle shift from the meaning its creators gave it, has endured. Perhaps this is because she was not the only one to see it that way. In 1903, when the poem was installed, 600,000 immigrants came through Ellis Island (at its peak in 1907 one million people came through). Each of them had a chance to ponder the meaning of the oxidizing copper sculpture as their ships arrived in New York harbor. The newly arrived immigrant looking up at the Statue of Liberty is one of the lasting images of the era of Ellis Island immigration.

During World War I this connection was made explicit by posters advertising war bonds. The posters invoked patriotism by reminding new Americans of their first glimpse of the statue.

Fifty years after its debut (and after federal legislation in 1924 largely cut off the flow of immigration through New York) President Franklin D. Roosevelt invoked the same imagery as he rededicated the statue. He said, “I like to think of the men and women who, with the break of dawn off Sandy Hook, have strained their eyes to the west for a first glimpse of the New World. They came to us – most of them – in steerage…They not only found freedom…but by their effort and devotion they made the New World’s freedom safer, richer, more far-reaching, more capable of growth.”

The Statue has represented immigration and refuge in the population ever since. In 1986[?] New York novelist Pete Hamill connected immigration and the statue. In a special edition of New York Magazine celebrating the statue’s centennial he wrote, “The Statue of Liberty is our most famous immigrant, conceived and born in France, carried across an ocean into the harbor, and, like so many millions of others, given space and dignity and function in New York.”

In the same magazine, Mario Cuomo, then Governor of New York, evoked a similar image: “My mother came here by ship from Italy, and her first glimpse of this great country was when she sighted the Lady of Opportunity, The Statue told my mother that if she and my father were willing to work hard and care about this nation, they would be able to share in its incredible bounties.”

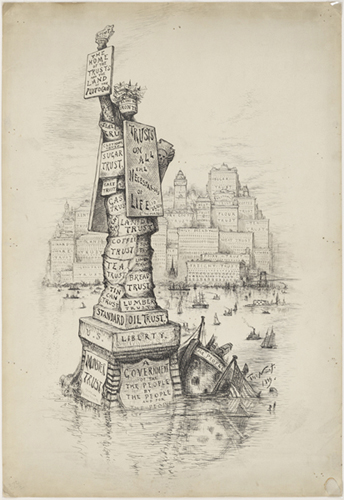

Emma Lazarus’s vision of the Statue of Liberty is not the only one to hold sway. The meaning of the large allegory in New York harbor has never been completely stable and is open to many different interpretations of the word “Liberty.” As Hamill wrote in 1986, “Over the past hundred years, she has been used to sell warehouses and war bonds. She has been cartooned and lampooned, made into a magazine and a musical. She has been held hostage by political radicals, sentimentalized by bogus patriots, appropriated, besieged, exploited by hustlers and cynics.”

“None of that seems to have mattered,” Hamill noted, ‘The wonderful old statue survives.”

So too do Lazarus’s words. For many they still give a powerful “raison d’etre” to the colossal green statue in the harbor.

The manuscript entered the collection of the Museum of the City of New York in 1936, the same year Roosevelt re-dedicated the statue. It was a gift of George S. Hellman, an author and collector and dealer of rare books, manuscripts, and artwork. The Museum’s records do not tell us how Hellman acquired the manuscript, nor why he gave it to the Museum of the City of New York rather one of the other museums that he supported, like the Morgan Library. It is possible he thought that the Museum of the City of New York, which had opened in its new Fifth Avenue building just four years earlier, was a more proper place for such a symbolic piece of writing.

Since then it has become one of the treasures of the Museum’s collection. In New York at Its Core, you can see the manuscript* along with two of Bartholdi’s original maquettes and learn how this piece of the New York story is woven into other topics, from the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, which opened in 1883, to the consolidation of the five-borough city in 1898.

* Due to the light sensitivity of the material, the original manuscript is not currently on view. A facsimile is on display in its place.