Loyalists Reunited! A Peek into the Edward Floyd De Lancey Collection of Family Papers

Tuesday, June 19, 2018 by

Since 1942, the Museum has been home to a fascinating set of papers collected by Edward Floyd De Lancey (1821-1905), a lawyer, historian, and writer descended from a prominent Loyalist family in New York City. The papers came to the Museum via the Mrs. Elon Huntington Hooker Acquisitions Fund, but their exact ownership prior to the acquisition remains a mystery. After arriving at the Museum, a sizable portion of the collection was gradually dispersed throughout the archives, but now, thanks to generous support from The Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation, it has been reunited, organized, and described, providing an engrossing glimpse into 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century life in the New York City region.

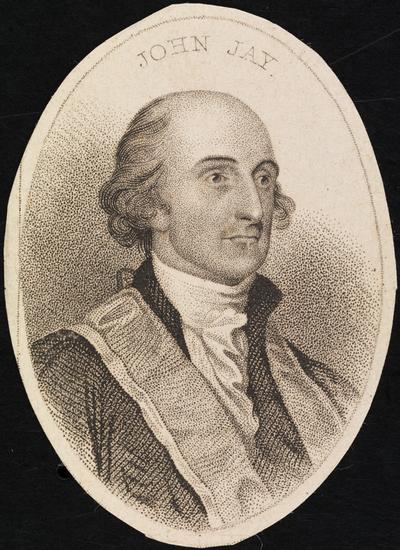

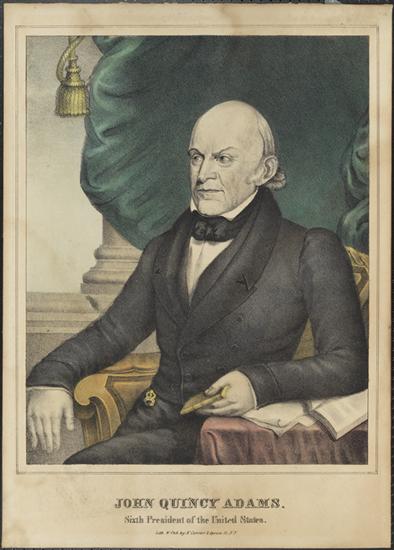

The project of reconstituting this historically significant archive was a true pleasure. It began with a compelling archival challenge: scour the Museum’s other collections and gather up everything I could find from the original De Lancey collection. Gradually, as the detective work paid off and more documents came to light, the original collection began to take shape. The Edward Floyd De Lancey Collection of Family Papers, as it is now called, documents the lives of several prominent families from the New York City region, specifically Manhattan, Long Island, and Westchester County. Comprising 715 items and with a focus on the Revolutionary War era, it includes correspondence to and from John Jay, John Quincy Adams, and a number of other influential New York City citizens. Other than the Jay family, all of the families represented in the collection were Loyalists who remained faithful to the British during the war, making the collection a rich and deep source of information about the personal and political lives of New York City–region Loyalists.

For Loyalists, reasons for remaining true to the crown varied in accordance with economic, racial, and regional contexts. The Loyalists represented within this collection were among New York City’s most wealthy and privileged citizens, and as such had obvious interests in maintaining the status quo. But in the war’s aftermath, defeated Loyalist families were sometimes violently attacked, their possessions confiscated; many formerly prosperous members of the Colonial elite found themselves run out of town, humiliated. Some fled New York for other areas of the British Empire. Some, including many in this collection, had their estates seized and were banished from the state as a result of the 1779 New York Act of Attainder. Some returned in the late 1780s, resettling in their original places of residence, but many remained abroad for the rest of their lives, having been granted seats of political power elsewhere in the British colonies. The De Lancey papers document this period of upheaval via extensive correspondence; legal, financial, and business documents; military papers and orders; genealogical material; and a broad range of real estate documents.

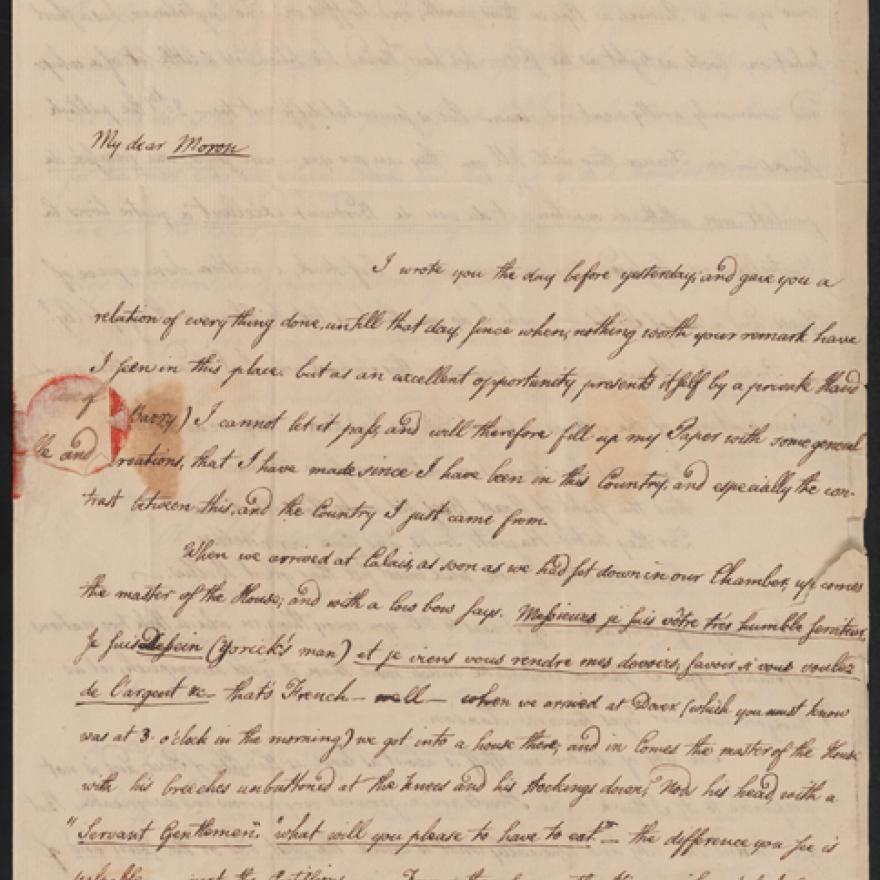

Notably, the collection also contains 243 pieces of correspondence to and from founding father John Jay, his son Peter Augustus Jay, his nephew Peter Jay Munro, and a young John Quincy Adams. These letters, spanning the postwar years 1783–1818, lay bare the close relationships among three Jay family members. John Quincy Adams’s letters to Peter Jay Munro provide an especially entertaining and absorbing depiction of a year in the life of the teenage son of founding father John Adams.

Choosing examples from the collection to highlight is a challenge, as so many convey such an abundance of historical information, but below are a few of my favorites. Check out the others in the Collections Portal!

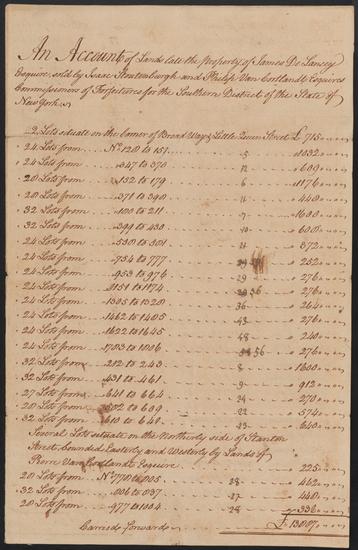

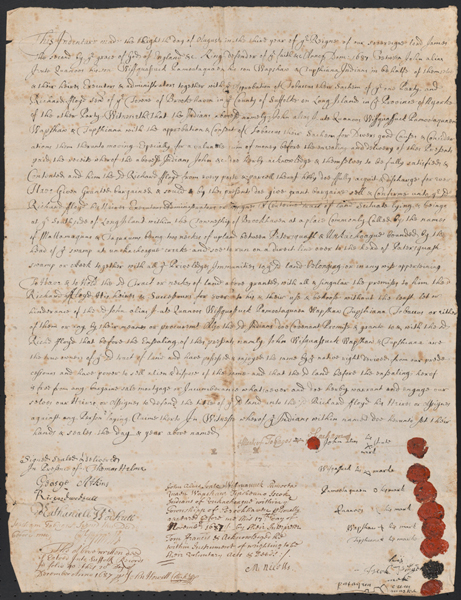

Page one of four related documents in the collection that hold particular historical interest concern the property of Chief Justice and Lieutenant Governor of New York James De Lancey (1732–1800), who as a Loyalist was attainted, his lands confiscated, under the 1779 Act of Attainder. These 1785–1791 documents tell the story of the seizure and eventual sale of De Lancey’s substantial Westchester County landholdings. This particular document, signed by Isaac Stoutenburgh and Philip van Cortlandt, Commissioners of Forfeitures for the Southern District of the State of New York, is an account of the sale of portions of De Lancey’s seized lands. Proceeds from the sale were sent to the New York State Treasury.

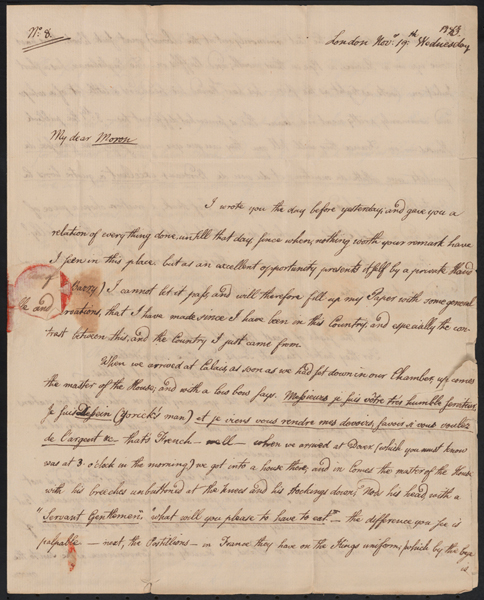

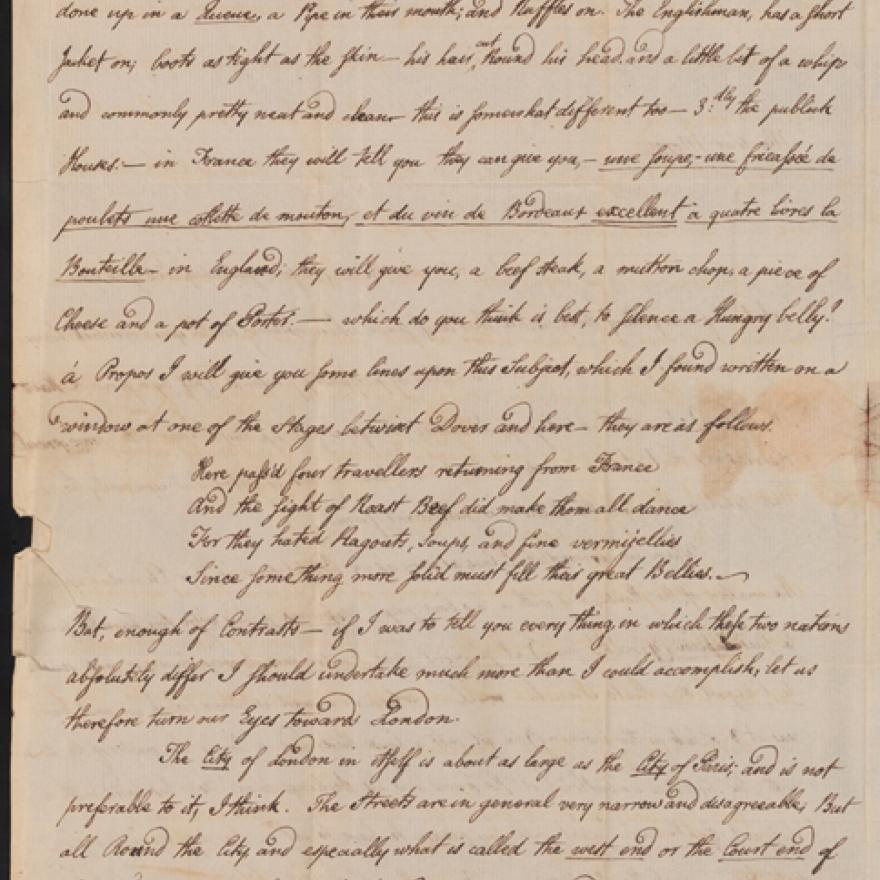

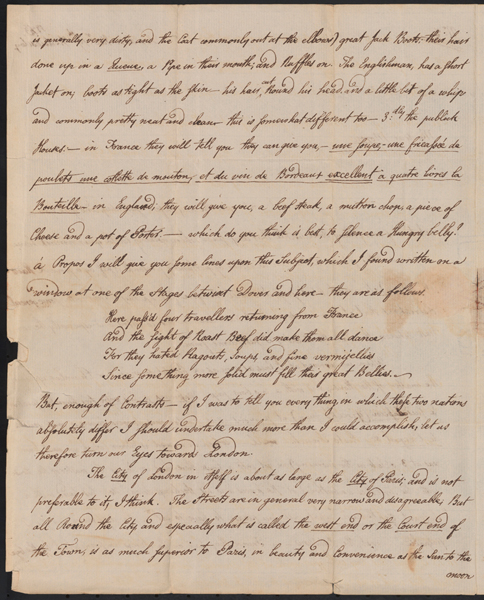

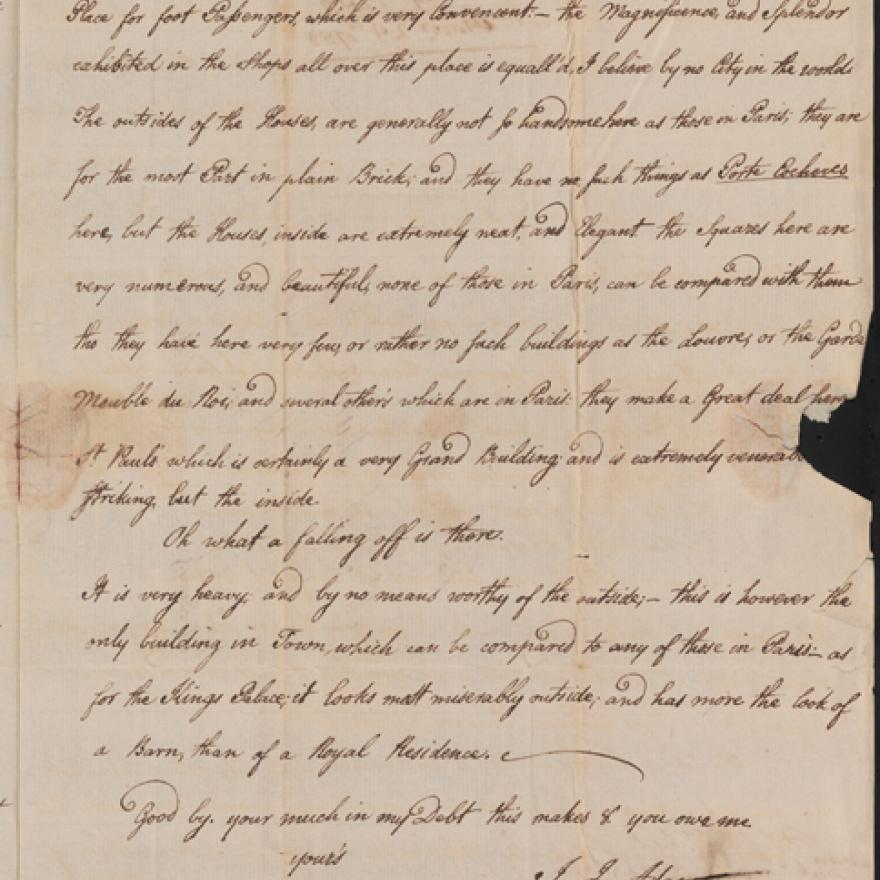

John Quincy Adams, seventeen years old at the time, writes exuberantly and playfully to his good friend Peter Jay Munro, nephew of John Jay. His sense of humor is evident in the prose; here he opens a letter with “Dear Moron,” a play on Munro’s last name.

This formal oversize deed is dated August 8, 1687, and conveys a parcel of land on the south side of Long Island from Native peoples to first-generation British immigrant Colonel Richard Floyd. The document is signed by Tobacus the Sachem, elder of the Unkechaug tribe of Long Island, and several other Native men, using signature marks and red wax seals.

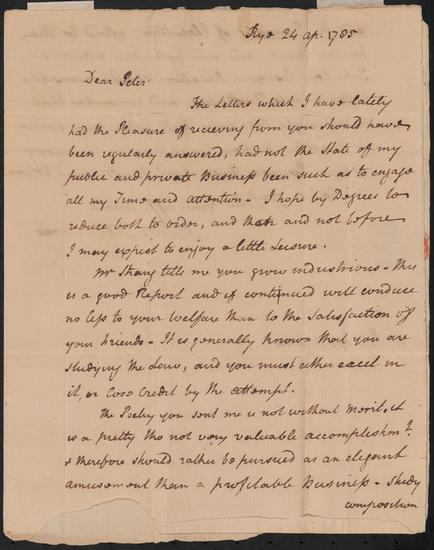

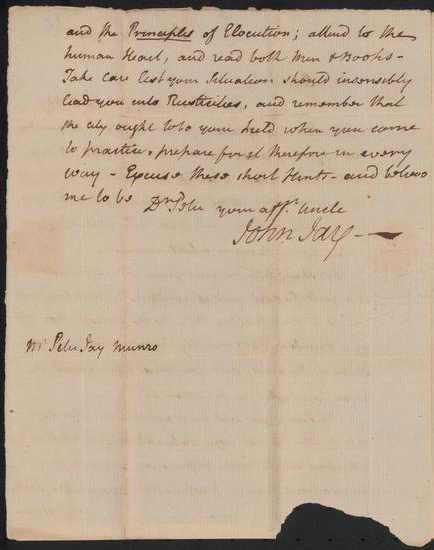

John Jay (1745-1829). Letter to Peter Jay Munro, April 24, 1785. Museum of the City of New York. 42.315.7.

In this letter from John Jay to his nephew Peter Jay Munro, written after Munro had penned and sent Jay a poem, Jay exhorts his nephew not to take up poetry as a profession. Here we find one of the many examples of Jay guiding his nephew, whom he had come to regard almost as a son, in matters of education, comportment, and career.

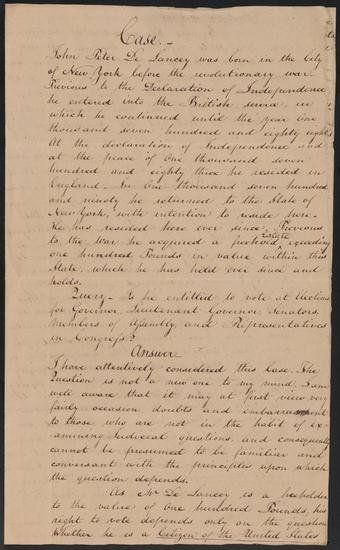

John Peter De Lancey, a British major who commanded a regiment of Pennsylvania Loyalists and participated in the battles of Brandywine and Germantown, lost his right to vote in light of his Loyalist views. De Lancey contested the decision, and in this 1800 legal opinion, the deciding judge, Peter Jay Munro (a relative of De Lancey’s by marriage), restored De Lancey’s right to vote, basing his decision on the concept that this right rested upon the question of whether De Lancey should be considered an American citizen or a British subject. Because De Lancey was a landholder, Judge Munro ruled that he was de facto an American citizen, and as such should hold the right to vote.