Jackie Robinson Day

Sunday, April 14, 2019 by

Each year on April 15, Major League Baseball celebrates Jackie Robinson Day ― a tribute to April 15, 1947, the day Jack Roosevelt Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers and became the first African American to play Major League Baseball in the modern era, finally integrating America’s “national pastime.” It is celebrated, noted Commissioner Bud Selig on the first Jackie Robinson Day in 2004, because, “no generation should ever forget what Jackie Robinson did.”

From January 31–September 22, 2019, the Museum presented In the Dugout with Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait of a Baseball Legend, an exhibition of never-before-seen photographs of Jackie taken for Look magazine. The exhibition considers how Look, a popular pictorial magazine on par with Life, depicted the moment when Brooklyn’s home team made civil rights history and includes three autobiographical essays Jackie wrote for Look in 1955, along with the article he wrote announcing his retirement from baseball in 1957. The photographs and articles present an intimate picture of the baseball player and civil rights icon.

When Robinson took the field that April day in 1947, there was no guarantee that he would succeed, or that he would be recognized every year throughout the League. Dodgers president and general manager Branch Rickey had signed Robinson to a minor league contract the previous year, concluding a three-year, $25,000 search for black players conducted under the guise of a the creation of a new Negro League team, the “Brown Dodgers.” At that time, Look magazine’s sports editor, Tom Cohane scoffed, “Nobody could reasonably suspect materialistic motives… Negro starts are not imperative to the pennant Rickey labors toward, nor could they improve attendance.” He even speculated, “in fact, signing Robinson may cost Rickey money.”

In fact, Rickey wagered that talent drawn from the Negro Leagues would earn him new fans, increased attendance, more press attention, and, hopefully, a shot at the World Series. To do this, Rickey needed someone who was more than just a talented ballplayer. He needed a player with the strength of character to withstand being targeted by fans, reporters, opponents, or even members of his own team because of his race. Rickey brought Robinson in for an interview, and told him, as Robinson wrote in Look, “that one wrong move on my part would not only finish the chance for all Negroes in baseball, but it would set the cause of Negro America back 20 years.” After meeting Robinson, Rickey knew he had found his man.

Yet, just being on the team didn’t automatically make Robinson a member of the team. In May of Jackie’s rookie year, New York Post sportswriter Jimmy Cannon observed, “in the clubhouse, Robinson is a stranger.” He went on, “It is obvious he is isolated by those with whom he plays… Robinson never is part of the jovial and aimless banter of the locker room.” He concluded, “He is the loneliest man I have ever seen in sports.”

Yet, by the end of the season, Jackie was awarded the very first Rookie of the Year Award, and the team had won its first trip to the World Series since 1941. Jackie himself recalled, “I had started the season as a lonely man, often feeling like a black Don Quixote tilting against windmills. I ended it feeling like a member of a solid team.”

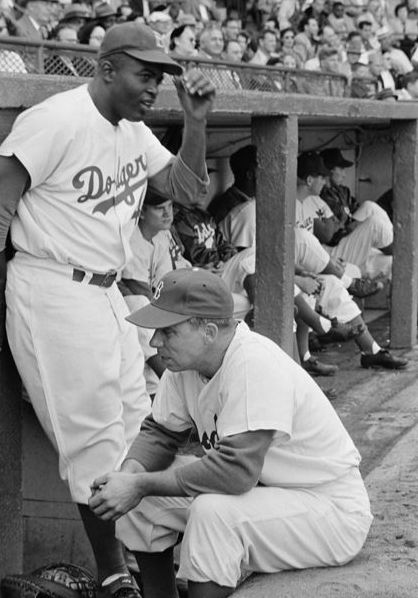

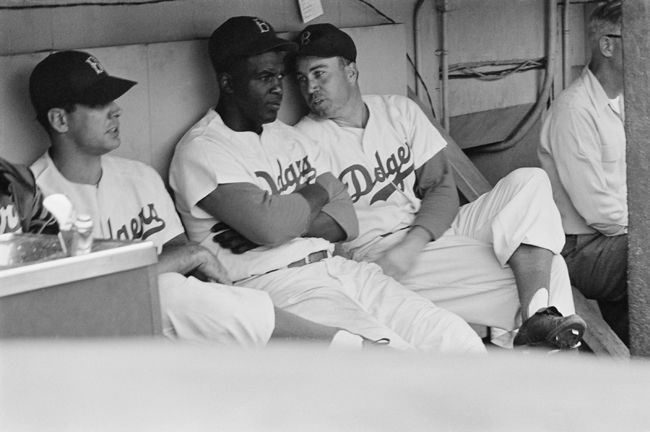

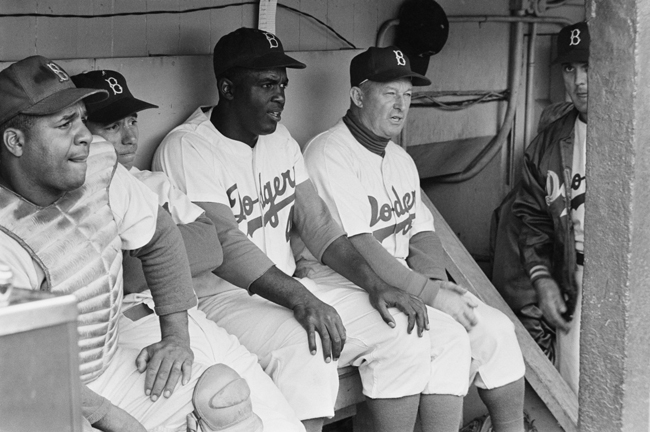

Two years later, in 1949, when Look magazine sent Frank Bauman to photograph Robinson at Ebbets Field he looks very much a part of the team. Robinson would win the National League MVP award that year and sportswriters noticed a shift. Sportmagazine’s Tom Meany wrote, “the trailblazing Negro has already attained his main goal ― to be thought of as just another ballplayer,” while Arthur Daley of the New York Times declared Robinson, “one of the gang” noting, “he didn’t wait to be invited to sit in at a card game. He started them, shuffling the cards and singing out cheerfully, ‘Who wants to play?’ Never did he want for takers.”

Even Look’s Tom Cohane came around, writing, “as a box office attraction, Robinson rates with Joe Di Maggio, Ted Williams, Ralph Kiner and Stan Musial” and noting his prowess as a base runner: “His wildfire leads cause balks by pitchers, poor and foolish throws by infielders and catchers. He invites situations. Rounding third, he dances down the line, dares the catcher to throw. Against his good judgement, the catcher throws. Robinson charges home.”

This change can also be seen in photographs taken by Kenneth Eide for Look in 1953. You see Jackie talking to team captain Pee Wee Reese, speaking casually with a teammate (probably Carl Furillo) in the locker room, hanging out with Roy Campanella or Duke Snider in the dugout, watching the game unfold.

Jackie’s team won the pennant in 1947, ’49, ’52, ’53, and, in 1955, the Dodgers won their first, and only, World Series as Brooklyn’s home team. They went to the World Series again in 1956, and Jackie announced his retirement from baseball in Look magazine in January of 1957. He wrote, “I’m glad my last season with the Dodgers was a good one and that I had a good Series…I’m glad I ended strong.”

Among his many accomplishments after baseball, Robinson became the first African-American vice president of a major American corporation, Chock Full o’Nuts, he served on the board of the NAACP, and helped found the African American owned Freedom National Bank. In 1962 he was the first African American inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Jackie’s uniform number, 42, was retired by the Dodgers in 1972, before his death in October that year.

Then, in 1997, on the 50th anniversary of Jackie’s debut with the Dodgers, #42 was retired throughout Major League Baseball at a Shea Stadium ceremony attended by Commissioner Bud Selig, Rachel Robinson, and President Bill Clinton. It was an unprecedented move ― #42 is still the only number retired throughout the League.

So, in 2007 when Cincinnati Reds’ Ken Griffey Jr. decided he wanted to wear Jackie’s number on Jackie Robinson Day, he needed special permission from Commissioner Bud Selig. He was granted that permission, and set off what The New York Times called, “an unforeseen grassroots movement” among players to pay tribute to Jackie by wearing #42.

That year more than 200 players, including the entire rosters of several teams, including the Los Angeles Dodgers, the Philadelphia Phillies, and the St. Louis Cardinals chose to wear #42. Here in New York, Yankees Derek Jeter, Joe Torre, Mariano Rivera (who’d been given Jackie’s number in 1995, before it was retired), and Robinson Canó (who was named for Jackie) wore #42. While the Mets decided that only manager Willie Randolph, the first African-American manager of one of New York’s Major League teams, would honor Robinson in that way.

At the time, Randolph told the Times, “Maybe the best thing about this year’s tribute is that it came from the players. You hear these jokes that the modern player doesn’t know anything about baseball history. But it’s pretty clear that most of them do appreciate what Jackie Robinson did for them ― all of them.”

But perhaps what Jackie did was as much for the fans as it was for the players. Speaking to fans who watched Jackie play during the years represented by the Look magazine photographs, one gets a sense of the impact he had on everyone who saw him. Fans (like my father-in-law who traveled by bus from Freehold NJ to Ebbets Field as a boy) still remember the first time they saw Jackie play, they remember his size, his grace, his remarkable ability. They recall the roar of the crowd when he came up to bat, and how when he was on first, he was bound to steal second, and when he ran for third, the pitcher was likely to over-throw third and send Jackie dashing to steal home. In 2004, Commissioner Selig remembered traveling to Chicago at age 13 to see Jackie play, noting, “I never saw such electricity, such drama.”

Since 2009 all uniformed personnel ― players, managers, coaches, and umpires ― wear #42 on Jackie Robinson Day. In 2010 the Times asked Gary Matthews, Jr., at the time the Met’s only African American player, what Jackie Robinson day meant to him, “There is going to be a kid sitting in the stands today who has no idea who Jackie Robinson is and he’s going to ask his mother or father, ‘Why is everybody wearing No. 42?’ And that father, that mother, is going to tell their son or daughter who Jackie Robinson was and why we are wearing 42 today. That, to me, is what this is about.”

All Photographs: Museum of the City of New York. The Look Collection. Gift of Cowles Magazines, Inc.

![Frank Bauman, [Jackie Robinson], 1949 Baseball player Jackie Robinson wears his Brooklyn Dodgers uniform and hat, with a baseball stadium in the background](/sites/default/files/X2011_4_12183_32.jpg)

![Kenneth Eide [Jackie Robinson] 1953 Jackie Robinson stands near the dugout during a game with the Brooklyn Dodgers](/sites/default/files/X2011_4_2583_53_95.jpg)

![Frank Bauman [Jackie Robinson playing second base at Ebbets Field, Roy Campanella catching] 1949 Jackie Robinson stands on second base during a game at Ebbets Field with the Brooklyn Dodgers](/sites/default/files/X2011_4_11814_27.jpg)

![Frank Bauman [Jackie Robinson running the bases at Ebbets Field] 1949 Jackie Robinson runs bases during a game at Ebbets Field with the Brooklyn Dodgers](/sites/default/files/X2011_4_11814_43.jpg)

![Frank Bauman [Jackie Robinson at bat] 1949 Frank Bauman [Jackie Robinson at bat] 1949](/sites/default/files/X2011_4_11814_47.jpg)

![Frank Bauman [Jackie Robinson, Dodgers dugout, Ebbets Field] 1949 Frank Bauman [Jackie Robinson, Dodgers dugout, Ebbets Field] 1949](/sites/default/files/X2011_4_11814_45.jpg)