The Historical and Personal Importance of Engraved Powder Horns

Thursday, December 13, 2018 by

Powder horns, engraved or plain, were remarkably necessary and personal possessions in Colonial America. While engraved horns would continue to be used throughout the 19th century, they were most common between the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, a fairly short period of time (1754-1783). Without a powder horn close by, firearms of this era were useless. Powder horns became even more important as their owners engraved them, revealing fascinating personal, historical, and geographical information.

The practice of engraving powder horns became popular around the French and Indian War because soldiers experienced prolonged periods of waiting, as much of their time on an expedition would be spent sitting in a fort or around a campfire. Powder horns were ideally carved with gravers, although sometimes with needles or even slowly with small knives. When the engraver was happy with what he had done, he would rub the horn with grease, wax, or ash in order to make the engravings pop against the light color of the horn.

Horns typically featured their owner’s name above all other possible information or art. If the owner was illiterate, or largely so, they may have only put their initials, or they would have had an educated fellow soldier engrave their name for them. Also common was the date that the horn was engraved, and details about the expedition that the soldier was on. War expeditions would have likely been seen as one of the most significant moments in men’s lives, and the horn would be a source of pride.

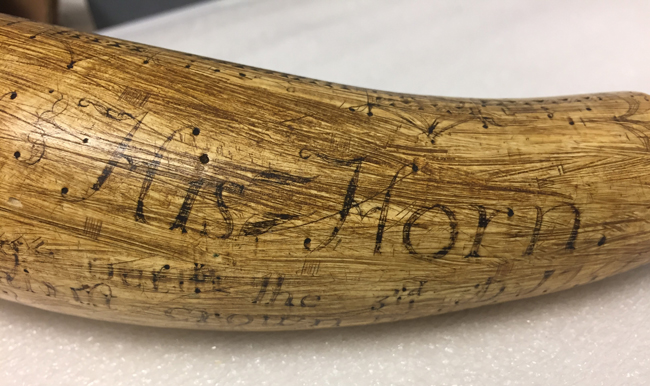

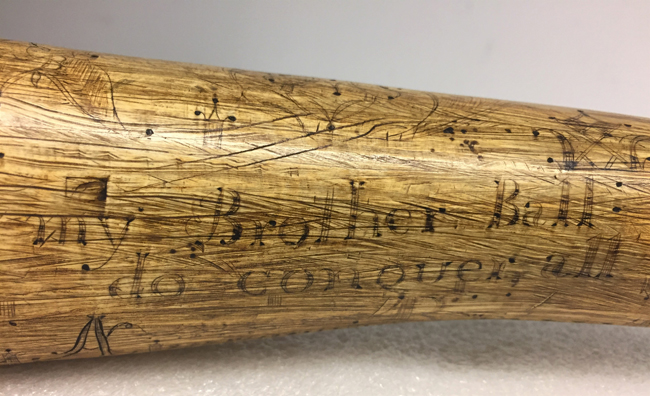

A fairly basic example that includes many features of a typical horn can be seen in the Museum’s collection. This horn reads, “Asa Elliot – His Horn. Made at Lake George Oct the 3rd AD 1756 in the expedition against crown point.” Asa Elliot (1727-1768), fought in the French and Indian War from April 11–November 25, 1756 in a British expedition to the French fort at Crown Point.

Elliot has also added a rhyme to his horn, which was a very common practice. Multiple variations of a core group of rhymes existed due to different literacy levels - as many engravers would have been spelling phonetically - as well as misremembering a rhyme that they heard from a fellow soldier. Elliot’s rhyme is indeed a variation of a very common one: “I Powder with my Brother Ball / A Heroe Like do conquer all.”

Also commonly found on powder horns were maps of everywhere that the soldier had been, or heard about from others. Maps of Upstate New York and Quebec would not have been readily available to the average soldier in the French and Indian War, which led them to create their own in real time. In this case, a soldier’s powder horn became ever more vital, as it was no longer just about being able to use your firearm, but also the ability to understand where you are.

An excellent example of this engraving practice can be seen in a powder horn engraved by a soldier named Matthew Watson sometime during the French and Indian War. Watson engraved a number of cities, settlements, forts, and bodies of water on his horn, including New York City, Albany, Fort Edward and Oneida Lake, which he has misspelled as “Lake Onyda.” Based on Watson’s usage of certain names of towns and forts, it is likely that he engraved his powder horn sometime between 1758 and 1763.

Another Museum powder horn from the 1750s features the names of two brothers, Abraham and Lucas Hooghkirk. The horn is only engraved close to the wooden plug on the wider end, and features a jumble of letters and images. These images include a mermaid, and hunter firing a musket at a deer, and a castle or otherwise large building.

Upon close investigation, the letters appear to be an attempt at a common powder horn rhyme, which is often written, “Steal not this horn for fear of shame / Above there is rite the owner’s name.” It seems likely that the horn was engraved by both brothers, perhaps at different times as Abraham was significantly younger. Lucas died in 1759 when he was only 24, and it may have been passed down to Abraham.

Engraved powder horns are an incredible historical resource, which allow us to explore the intimate realities of war and life in Colonial America. These powder horns are just a small part of my current project, as I work to inventory and research the Museum’s collection of weapons and weapons-related objects.