From Harlem to Hanoi: Dr. King and the Vietnam War

Wednesday, January 10, 2018 by

As we celebrate the opening of King in New York, we look back at what is perhaps one of the iconic figure’s least appreciated speeches—which took place here in New York. On April 4, 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a controversial sermon opposing the Vietnam War at Riverside Church in Morningside Heights, then helped lead a large antiwar march from Central Park to the United Nations later that month. Several photographs from the Museum’s collection provide a glimpse into King’s antiwar stance, New York’s role as a key site of activism around the Vietnam War, and the global scope of the civil rights movement.

Most Americans know of King’s “I Have a Dream Speech,” but many still have not heard or read “Beyond Vietnam.” King spoke many times at the Gothic cathedral on 120th Street and Riverside Drive in Manhattan—long a center for lively political discussion—and on that early spring day, a large crowd filled its halls, with more listening through loudspeakers outside. Repudiating warnings of his advisors, and building on past antiwar comments he had made, King emphasized his religious beliefs against violence, self-determination for all peoples, and the war’s toll on the poor—who faced dwindling resources for anti-poverty programs at home and disproportionate casualties in Vietnam. In addition to urging “a revolution in values,” King called for a cease-fire and removal of all troops in Vietnam, and for Americans to oppose the war and resist the draft.

King built upon his position by returning to New York for the April 15, 1967 Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam. Envisioned by New York-based pacifist and clergyman A. J. Muste, and organized by a loose coalition of antiwar groups chaired by civil rights activist James Bevel that became known as “the Mobe,” between 125,000 and 400,000 protestors from the city and beyond took to the streets in one of the largest mobilizations against the war. Protestors gathered in Central Park and marched downtown to the UN for speeches and a rally. The march was largely nonviolent, but some protestors burned their draft cards, while others were pegged with eggs and paint by those who opposed their antiwar positions. King led the march arm-in-arm with other leaders, as shown in the photograph above with Dr. Benjamin Spock and Monsignor Rice of Pittsburgh, and spoke by the UN.

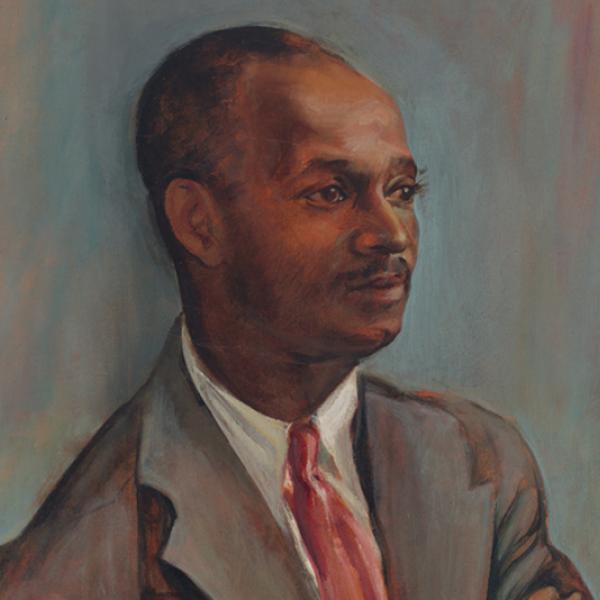

Nearly all of King’s advisers had discouraged him from his antiwar activities, arguing that it would ally him with a range of marginalized peaceniks, dilute his campaigns for racial equality, and ruin his relationship with President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Sure enough, King’s Riverside Church speech garnered widespread criticism from media outlets and other civil rights figures. The New York Times called it “wasteful and self-defeating,” and King’s relationship with Johnson soured. Critics argued that civil rights and antiwar activism should remain separate. Benedict J. Fernandez’s photographs of King, taken by the New York-based photographer and teacher over several months, provide a glimpse into the internal conflicts and obstacles that put King in a somber mood by 1967.

In fact, many civil rights activists opposed the war in Vietnam. The April 15 march drew a large interracial crowd and a strong contingent of local antiwar activists from Harlem, and its speakers included Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) leader Floyd McKissick and former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) leader Stokely Carmichael. The year prior, SNCC, which had its fundraising headquarters in New York, had spoken out against the war, tying violence in the U.S. South to war in Southeast Asia. And African-American activists had long used the United Nations in particular to link racism at home with violence around the world. King’s speech explicitly addressed the critique that “peace and civil rights don’t mix,” characterizing his activism as a quest to “save the soul of America” that also included U.S. actions abroad. King’s participation in the April 1967 antiwar events shed light not only on the city’s role as a center for antiwar and civil rights activism, and the connections between them, but also speaks to New York’s role as a global city.

Martin Luther King was killed on April 4, 1968, exactly one year after his speech against Vietnam from Riverside Church. Among many memorials to King is the one pictured above, by William Tarr, which opened in 1974. It stands in front of what is now the Martin Luther King Jr. Educational Campus in the Lincoln Square neighborhood of Manhattan, not too far from where the 1967 antiwar march set off from Central Park.

Visit King in New York (open through June 24, 2018), which reveals a lesser-known side of King’s work and demonstrates the importance of New York City in the national civil rights movement. And learn more about New York’s role in the civil rights movement and activism surrounding the Vietnam War in the Museum’s ongoing exhibition Activist New York.