Guido Bruno: A Literary Vagabond

Tuesday, February 27, 2018 by

Guido Bruno, one of Greenwich Village’s most revolutionary figures, has been largely forgotten in the pages of history. Active in the Village in the 1910s, Bruno produced a number of successful monthly publications, consisting of his own writing and the writing of others. He also curated a number of exhibitions, showing the work of underrepresented New York City artists. Known for his unique writing and unwaveringly progressive political views, Bruno made a name for himself among the literary and artistic scene of Greenwich Village. Throughout his career, he had many run-ins with the Comstock Law and the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, which sought to enforce the law by suppressing the circulation of anything it deemed “obscene.”

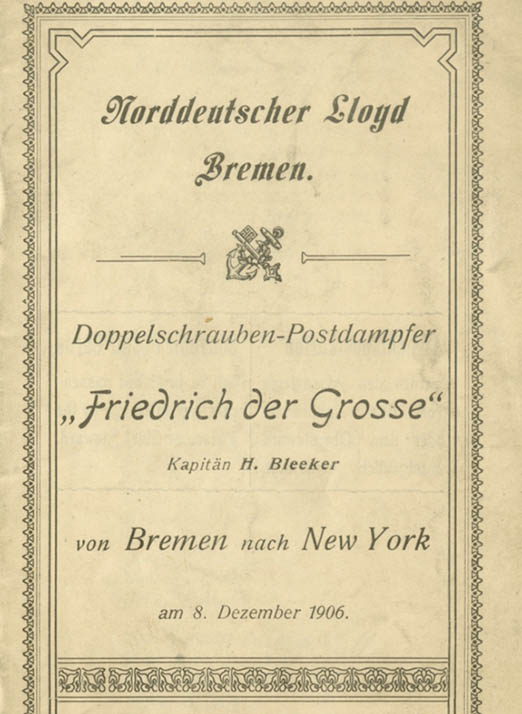

Born Curt Josef Kisch in a small town north of Prague in 1884, Bruno was raised in a German-speaking Jewish family. His two younger brothers, Guido and Bruno, inspired the pseudonym that he would use for much of his life. Against his family’s wishes, Kisch developed a love of writing and forewent medical school, and boarded a steamship bound for America at the age of 22.

Kisch eventually found himself in Chicago where he began publishing The Lantern, a monthly magazine that contained works by himself and other writers. The Lantern also contained social commentary from Kisch, often regarding the difficult lives of sex workers and laws that punished only women. His commentary violated the Comstock Law and he was fined $400, marking his first run-in with social purists. This significant expense led to the end of The Lantern, as well as the end of Kisch’s time in Chicago. He moved to New York City in 1913, legally changing his name to Guido Bruno.

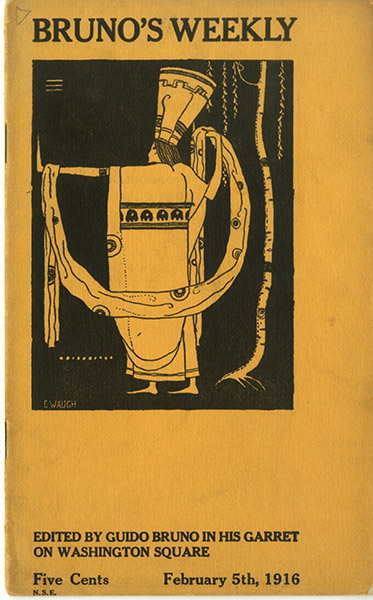

Once in Greenwich Village, Bruno began to write full time. He worked out of his garret, the second floor of a tiny wooden building at Washington Square. Here, he produced a wide array of monthly and weekly publications, including Greenwich Village, Bruno’s Weekly, and Bruno Chap Books. Bruno would also curate exhibitions highlighting the work of lesser known artists. These exhibitions, and many other events and lectures produced by Bruno, were free of charge in an effort to bring art and entertainment to everyone.

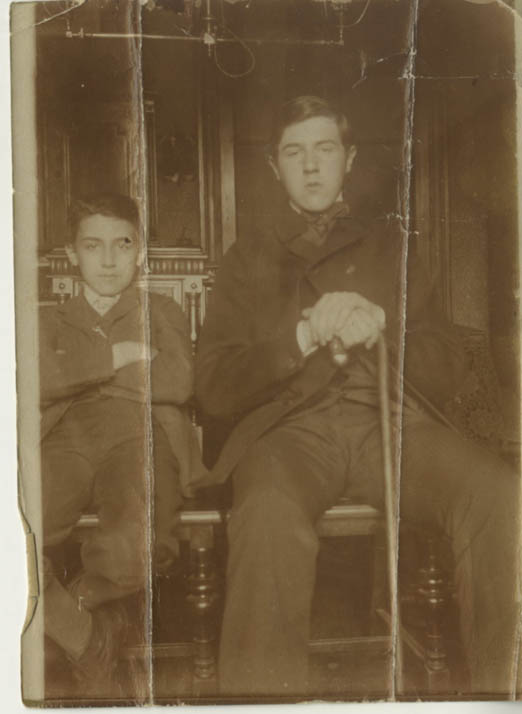

Bruno’s fame in the Village continued to grow and he was profiled often in newspapers. One referred to him as the “mayor of the Village,” and another, “a literary vagabond.” He was photographed, sitting proudly at his desk, surrounded by books and manuscripts.

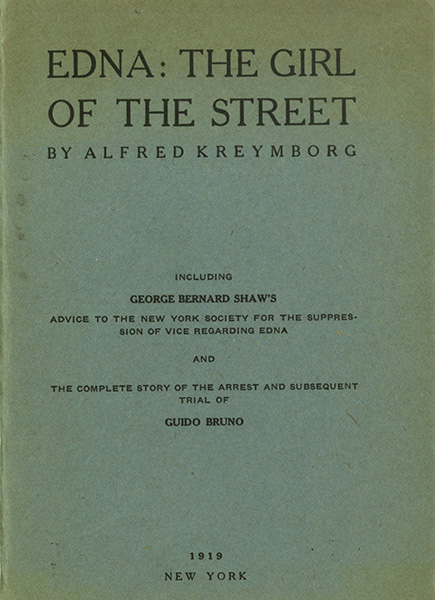

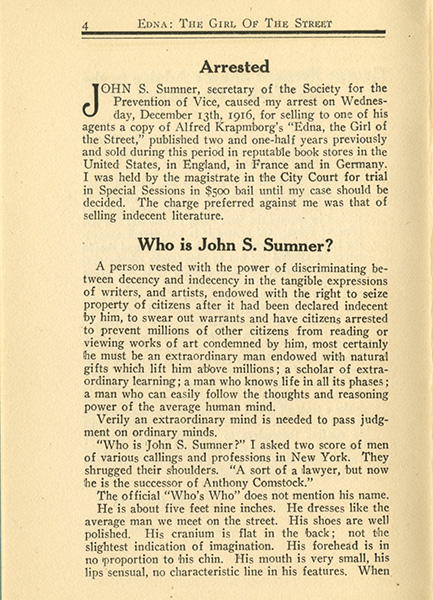

After a devastating fire in his garret in 1916, Bruno opened a bookstore, The Garret Shop. Almost immediately after opening the store, Bruno encountered a patron who asked for a Bruno Chap Book entitled Edna: The Girl of the Street by Alfred Kreymborg. Similar to Bruno’s past writings about sex workers, Edna discusses the difficult lives of women. The patron was revealed to be an agent for John S. Sumner, who was the successor for Anthony Comstock as the head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Bruno was arrested for the same crime of violating the Comstock Law.

Bruno immediately spoke out against his own arrest, and published a scathing pamphlet criticizing Sumner. He wrote, “[Sumner] is the grand inquisitor of an obscure age who could have flourished five hundred years ago, but who is entirely out of place in our era … one hundred millions of American citizens are curtailed in their freedom of reading whatever they may choose.” Bruno was put on trial and ultimately acquitted, but the cost of his defense depleted all of his savings.

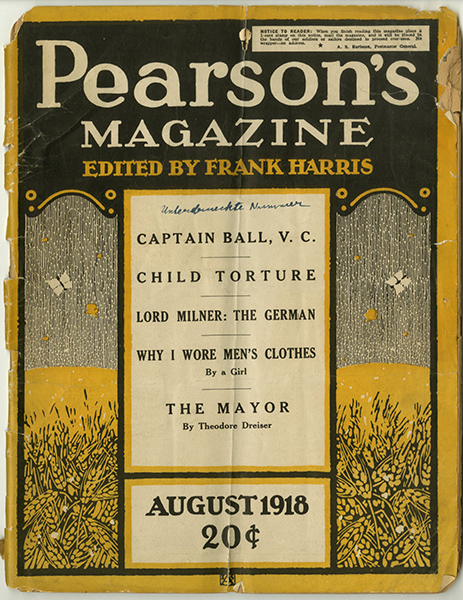

Bruno then began working for his friend, Frank Harris. Harris, an Irish writer famous for his provocative memoir, My Life and Loves, was the editor of Pearson’s Magazine. Bruno became Harris’s second-in-command for the magazine, and throughout World War I Pearson’s was socialist and anti-war, a position they maintained after the war ended. Once again, Bruno got into trouble with the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice after writing a piece under a female pen name about a woman who dressed as a man in order to avoid sexual assault and obtain equal rights and economic independence. Instead of being fined or brought to court, the circulation of that issue of Pearson’s was significantly delayed.

For more about the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and its frustrations with the likes of Guido Bruno and the circulation of “obscenity”, visit the “Social Purity” case in the Museum’s Activist New York exhibition.

![A museum photo by A. B. Bogart of [Guido Bruno] in 1915.](/sites/default/files/F2012_58_186.jpg)