The Glass Ballot Box and Political Transparency, 1856/2020

Tuesday, November 3, 2020 by

News of the upcoming elections has filled our consciousness for months on end. For many, it seems as though politics has never been more heated, with contentious debates, accusations of fraud and corruption, widespread concerns about the election infrastructure and voter suppression, and sparring between politicians and the media—and amongst different media outlets. Yet this is nothing new. In 1856, the United States was embroiled in conflicts that might seem familiar to today’s readers: income inequality with ever-increasing disparity between the rich and poor, frequent anti-immigrant sentiment, and accusations of political corruption and nepotism. When Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper revealed news of a “stuffer’s ballot box” designed to conceal pre-marked ballots to sway an election, concerned citizens across the country voiced their outrage. In response to this news about election tampering, New Yorker Samuel Jollie proposed a novel solution: a ballot box made of glass.

Presenting himself at the Mayor’s office, the music publisher, who had operated an establishment at 385 Broadway selling pianos, sheet music, and other musical instruments, unveiled his invention. Those huddled in the office witnessed a transparent glass globe hovering in an architectural armature of iron columns, revealing its gleaming, crystalline interior. Its columns curve and swell, evoking the legs of a Windsor chair, which had so famously supported American patriots who drafted the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution in Philadelphia. Openwork designs on its top and bottom suggest acanthus leaves, lightening its cast iron density and allowing patterns of light to play upon the curved glass surface while also evoking classical ornament. At the very center, like the bulls’-eye of a target, is a circular opening that would admit ballots, smaller than a dime but slightly larger than the diameter of a pencil, suggesting that the ballots would have to be tightly-rolled, like a cigarette. Overall, the form suggests one half of an hourglass, its globe displaying the votes that had been cast.

The New York Board of Councilmen enthusiastically embraced the design, which they described as “a perfect remedy” for concerns about election rigging, citing its “perfect security and inviolability.” While the city of New York wasted no time in placing an order of nearly 2,000 boxes in advance of the 1857 fall elections, the New York State Assembly declined to adopt the boxes state-wide, and so the design was confined to use at New York City polls.

Jollie’s boxes continued to be used in New York elections for the next forty years or so. As Jollie had promised in his patent application, the box “shall at all times exhibit the condition of the ballotings…In this way it will be obvious that the bystanders can see whether every ballot that is put into the hole actually goes into the box, and whether more ballots go into the box than are actually put through the ballot hole at top.” The visibility of the process was thought to eliminate possibilities of ballot box stuffing or fraud. As the London-based publication, The Graphic recounted, “In view of all present, including the voter, the other inspector, and the two registrars, the inspector rolls in the form of a cigarette each ballot and pushes it through the hole in the cover of its destined globe. … When the polls close at sunset the globes, still locked, are given to another set of inspectors, whose business it is to open them and count the votes” (23 November 1872, 479).

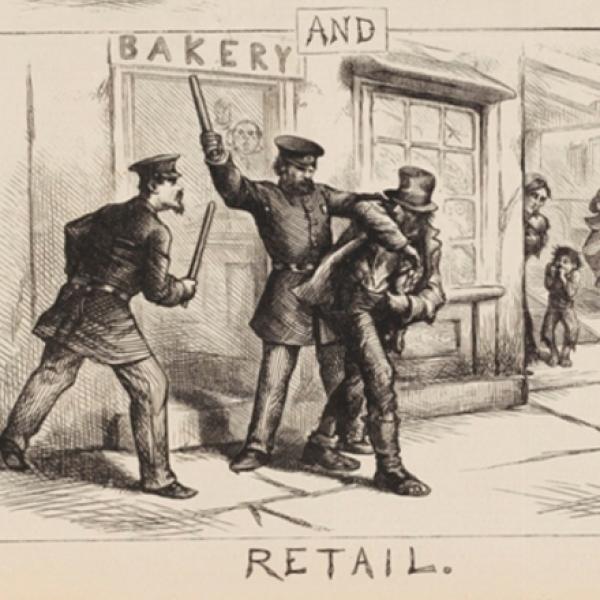

Jollie’s design for ballot boxes quickly became an icon of the democratic process, its distinct form showing up in dozens of political cartoons and even providing the inspiration for a campaign torch to be carried in night-time processions. Whether this is an indication of the New York-centered publication world or the appeal of its form, the box’s central glass globe and fluted columns appear throughout the latter decades of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Its use across the political spectrum showed that it could convey a wide array of sentiments.

Imagery of Jollie’s boxes was deployed in a variety of political cartoons and allegorical images that indicate the conflicts and struggles of different historical periods, representing both threats to and promises of democracy. In Thomas Nast’s 1871 “Victory Over Corruption”, an allegorical figure of America gestures triumphantly at an enormous Jollie ballot box, which flattens and crushes the figures of Boss Tweed and his Tammany Ring under its weight; Uncle Sam busily pastes up a broadside proclaiming “The ballot is mightier than the bullet” as onlookers cheer, a victory for the democratic process and political transparency.

Yet in one of the most marked examples from the contentious early 1870s, Boss Tweed leans with a scowl against a table on which the ballot box rests, his round belly echoing the form of the spherical ballot box; a sign notes “In Counting There Is Strength.” Tweed, smoking his cigar and with his hand in his pocket, unperturbed, is captioned as asking the reader “‘As long as I count the Votes, what are you going to do about it?’” Although Jollie’s box aspired to transparency and an end to fraud, Nast here points to the pragmatic concerns about the possible continuation of corruption and election manipulation. Here, the “machinery” of vote counting and tallying threatened to undermine the investment in the new ballot boxes. Despite the greatest hopes in the technology and material of the boxes, the process of voting and tallying was still open to manipulation and corruption.

The glass box and its representations were used to embody hopes and fears about American culture and its body politic, alternately assuaging anxieties about fraud or expanding voting rights, or serving as a vehicle to stoke the flames of racism, sexism, and class conflict.

While evidence suggests that the Jollie boxes were taken out of circulation by around 1895, the emblem of the glass globe ballot box with its four fluted columns continued to proliferate across media, including in many pro-women’s suffrage publications. Artist Lou Rogers deployed the icon of the ballot box in several of her pro-suffrage illustrations, using its form as a key icon that encapsulated the many responsibilities of participation in a democratic society.

Yet by the time women secured the right to vote (in 1920), Jollie’s glass ballot box had become an old-fashioned curiosity, rather than a cutting-edge invention. So far had the ballot box fallen from its once-exalted position that by the late 1920s, it could be found in the pages of the Bannerman Catalogue of Military Goods alongside surplus army uniforms and wartime relics, incongruously advertised on a page of “Belt Buckles and Miscellaneous Military Goods” (1927).& Bannerman, who also sold his military surplus wares and weapons from a massive storefront at 501 Broadway, listed it as a “NEW YORK CITY OLD-TIME BALLOT-BOX, relic of the days when Boss Tweed ruled the city. Can be used as an aquarium… heavy glass globe… weighs 39 pounds. Top, bottom and frame artistic iron casting, good glass; will make a splendid fish globe. Must have cost the city $50.00 each. Our bargain price, $2.85.” Rather than a proud icon of democracy Jollie’s box was reduced to an overstock “bargain” and affiliated with Boss Tweed, associating it with the very corruption it was designed to prevent. Once regarded as a key component of the sacred sphere of the election process, Jollie’s box, with its confused historiography, was now available at a “bargain price” to anyone with purchasing power, with a suggested repurposing of holding not votes but pet fish, a leisurely spectacle for a family living room.

Far from being the immediately recognizable icon of democratic elections that it was in the late nineteenth century, the Jollie ballot box has primarily been forgotten. Yet its design evokes much of the inspirational lexicon that people still employ during campaigns and elections: desires for transparency and neutrality, references to a grand democratic, republican past, calls for order, symmetry, durability, and strength. Although the Jollie box is now devoid of ballots, it remains a potent object in current discussions of political transparency, fairness, and the sanctity of the franchise. Just as the hanging chad, the butterfly ballot, and the Diebold voting machine came to exemplify fears and anxieties about voting, democracy, and representation at the turn of the twenty-first century, Jollie’s box is a compelling embodiment of nineteenth- and twentieth-century election concerns. Its luminous transparency and historical deployment in political cartoons that alternately mocked and elevated different demographics of the voting and non-voting populations continue to resonate with debates about voter ID laws, concerns about voter fraud, and competing claims of political transparency. Amid outcries about the possibilities of election rigging or the hacking of electronic voting machines, Jollie’s transparent ballot box reminds us that the democratic process has always been a contested sphere.

For more on the glass ballot box, see Foutch’s 2016 article “The Glass Ballot Box and Political Transparency”