Florence Mills: Broadway Sensation of the 1920s

Tuesday, March 24, 2020 by

In his memoir, Langston Hughes wrote, "Shuffle Along was a honey of a show.” Broadway’s first all-black production since before WWI was, “swift, bright, funny, rollicking, and gay, with a dozen danceable, singable tunes.” The book was by veteran comedy duo Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, and the lyrics and music were by the songwriting team Nobel Sissle and Eubie Blake, and everyone, from the writers to the musicians to the dancers, were black. It was the second-longest-running Broadway production in 1921, and The Washington Herald declared it “Summer’s biggest hit.”

“Besides,” Hughes went on, “look who were in it: The now-famous choir director, Hall Johnson, and the composer, William Grant Still, were part of the orchestra…and Caterina Jarboro, now a European prima donna, and the internationally celebrated Josephine Baker were merely in the chorus.” And, he notes, “Florence Mills skyrocketed to fame in the second act.”

Florence Mills (1896-1927) is one of nearly 70 New Yorkers you can virtually “meet” if you visit the Museum’s permanent exhibition New York at Its Core. We’re bringing her to you #MuseumFromHome in honor of Women’s History Month.

Shuffle Along was Florence Mills’s Broadway debut, but she had been a performer long before that. Throughout her career as a singer and dancer she confronted racial stereotypes, broke down barriers, and won over black and white audiences alike. Her story, like that of many performers of her generation, illustrates the limitations and opportunities of black performers in Jazz Age New York.

Like one million black southerners who abandoned rural life for the industrial centers of the north between 1900 and 1929, Mills' parents moved from Lynchburg, Virginia to Washington DC, where she was born, and then to New York and Chicago. New York City’s black population increased by 66% during what is known as the Great Migration, and Harlem transformed into an African-American urban enclave.

Opportunities for black performers in Mills’s day were limited by the long history of blackface minstrelsy. Songs, dances, and comedy drew on stereotypes of southern black life or “exotic” imagery. Performances were often segregated, and even black performers might wear blackface to entertain white audiences. Offensive by today’s standards, this material may have been perceived differently at the time.

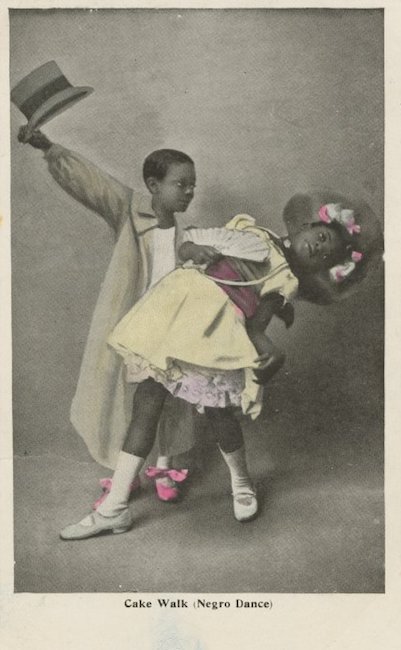

As a child, Mills performed the kind of roles open to black children, first appearing onstage at DC’s Bijou Theater at the age of 3. She was a champion of the “Cake Walk,” a dance satirizing white upper-class culture, but usually performed for white audiences; and she performed the role of a “pickaninny” (a black child who was part of a white act) with a burlesque star known as Bonita. Later she performed in cabarets and reviews in Chicago, and with traveling vaudeville acts including the Panama Trio with Cora Green and Ada “Bricktop” Smith which performed for mixed audiences at Chicago’s white-owned Panama Club; and the Tennessee Ten with her future husband and manager Ulysses “Slow Kid” Thompson, which toured black vaudeville theaters throughout the south, midwest, southeast, and northern cities.

Mills returned to New York City in 1920 at the start of an explosion of black intellectual and popular culture called the Harlem Renaissance. Jazz, a style of music with origins in black musical traditions of New Orleans and Chicago had just arrived in New York. While at the same time, black writers, artists, performers, and intellectuals, were creating a distinctive Harlem culture.

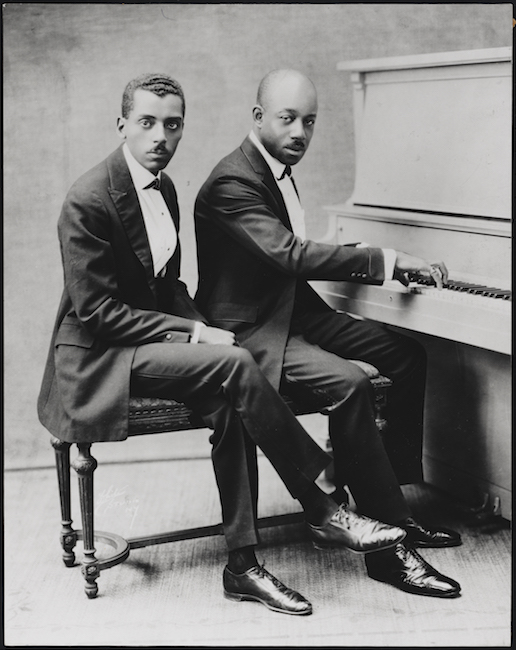

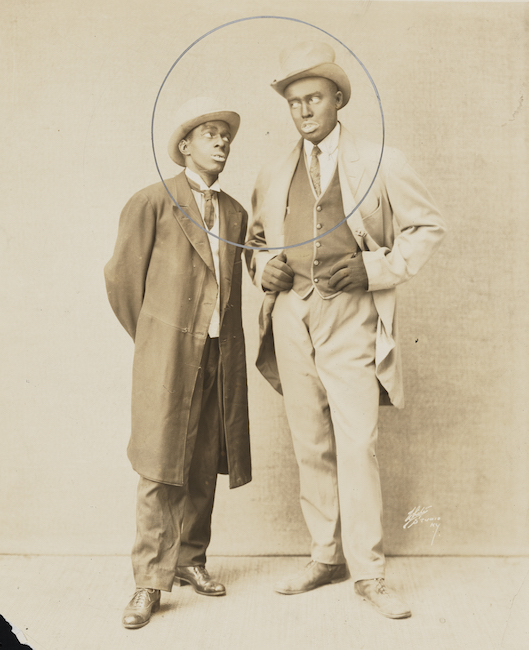

The Harlem Renaissance was a highpoint in the visibility of black performers in New York, but it had roots in the 19th century. Before World War I a network of groundbreaking black performers formed the Frogs, a professional organization for African Americans in the theater and the arts. The founding members, pictured here in 1908, included the comedy duo Bert Williams and George Walker who created successful all-black musical reviews in the early 1900s; Lester Walton, the drama critic for The New York Age and manager of Harlem’s Lafayette theater; pioneering bandleader James Reese Europe who led the first black orchestra (The Clef Club) to play at Carnegie Hall, and who would bring American jazz to Paris as leader of the 369th Infantry band during World War I; and J. Rosamond Johnson, who with his brother James Weldon Johnson, composed “Lift Every Voice and Sing” which the NAACP dubbed “the Negro national hymn” in 1919.

In fact, it was at an NAACP meeting led by James Weldon Johnson in 1920 that the songwriters Sissle and Blake met sketch comedians Miller and Lyles, and the idea for an all-black Broadway show was born.

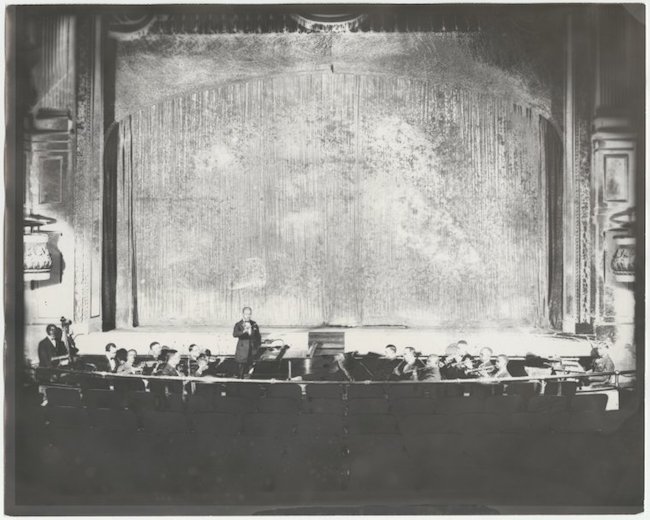

After a long tryout on the road, Shuffle Along opened on May 23, 1921, at the 63rd Street Music Hall, a venue not exactly on Broadway, and not exactly suited for a musical—the first row of seats had to be removed to make way for the orchestra pit. But the show broke ground in a number of ways. Orchestra seating was integrated (a Broadway first). And the plot disrupted some of the conventions of minstrelsy: Although some performers wore blackface, the plot centered on a romance between two black characters, which was taboo at the time. Ticket prices eventually rose to $3.00 and the show ran for some 500 performances, just 66 shy of that season’s record holder, Sally, a Florenz Ziegfeld production staring Marilyn Miller.

Reviews and word of mouth carried the production. The music introduced syncopated rhythms to a Broadway audience. The Daily Mirror exclaimed, “You may resist Beethoven and Jerome Kern, but you surrender completely to this…the music is as…heady as absinth.” While the New York Herald Tribune praised the dancers, “they fling their limbs about without stopping to make sure that they are securely fashioned on.”

When Mills joined the show in August, she sang the show stopper “I’m Craving for that Kind of Love.” Sissle declared she was, “Dresden china, and she turns into a stick of dynamite.” After the success of Shuffle Along proved that a black artist could make it on the Great White Way, Mills left the show to work with producer Lew Leslie (the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants) on two projects in 1922, The Plantation Revue, which began as an after-theater revue on the roof of the Winter Garden and moved to Broadway’s 48th Street Theater, and From Dover Street to Dixie which brought Mills to London in 1923, where she was a hit, “our prejudices…melt away when Florence Mills begins to sing,” wrote a British critic.

Then, in 1923 Ziegfeld offered her a starring role in the Follies. She would have been the first black woman on that stage, surrounded by Ziegfeld’s all-white girls. Instead, Mills chose to work with Lew Leslie again, this time on From Dixie to Broadway with an all-black cast. She took the role, she said, to “give my people the opportunity of demonstrating that their talents are equal.” Dixie to Broadway became the first full-scale production with an all-black cast in a proper Broadway theater when it opened at the Broadhurst, charging a record ticket price of $3.30.

Throughout her career, Mills chipped away at the stereotypes and limitations that clung to black performance, breaking several color barriers. Some of her numbers played old stereotypes for comedy, but she was also praised for the dignity of her singing. Her song “I’m a Little Blackbird Looking for a Bluebird” from the show Dixie to Broadway was seen as an anthem for racial equality — the “bluebird” represented freedom and happiness.

In 1925 she was photographed by Edward Steichen for Vogue becoming the first black person featured in a full page in the magazine, and in 1926 she was the first black artist to sing at New York’s Aeolian Hall, a venerated classical venue, when she performed an avant-garde work called Levee Land composed by Shuffle Along alum William Grant Still.

In 1927 Mills was touring in London with another Leslie production, Black Birds, after a successful run in Paris, when she fell ill and died upon returning to New York. Her death cut short a pioneering career, yet her legacy can be seen in the emergence of both the Harlem Renaissance, and the flowering of black performance on Broadway and in Harlem night clubs during New York’s Jazz Age—from the Charleston, a dance craze introduced in 1923’s Runnin’ Wild produced by George White with Miller and Lyles to Bill “Bojangles” Robinson’s stair dance in Leslie’s Blackbirds of 1928.

For Langston Hughes, black performances like Mills’s presaged the rest of the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote, “certainly it was…Shuffle Along, that gave a scintillating send-off to that Negro vogue in Manhattan, which reached its peak just before the crash of 1929...It gave just the proper push—a pre-Charleston kick—to that Negro vogue of the ’20s, that spread to books, African sculpture, music, and dancing.”