A Fine Line: The Art of the Clothesline

Tuesday, August 7, 2012 by

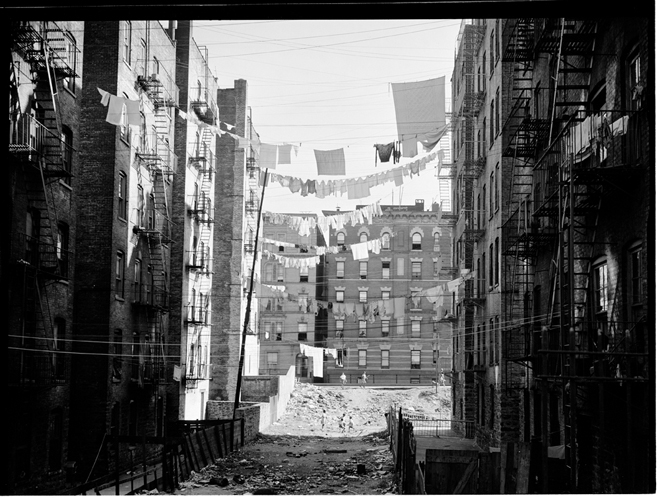

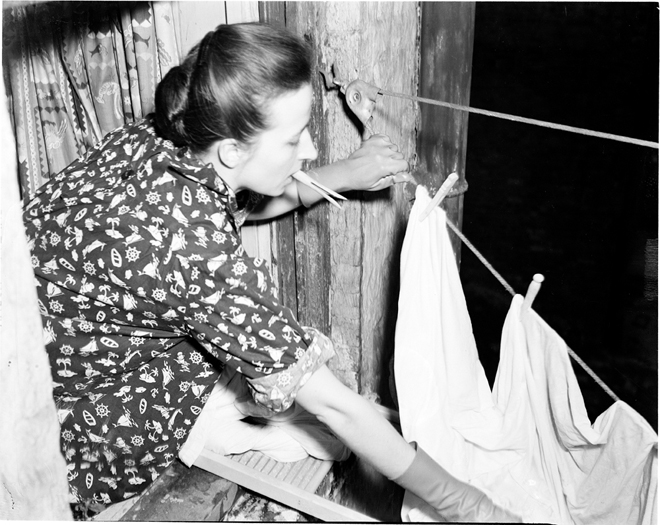

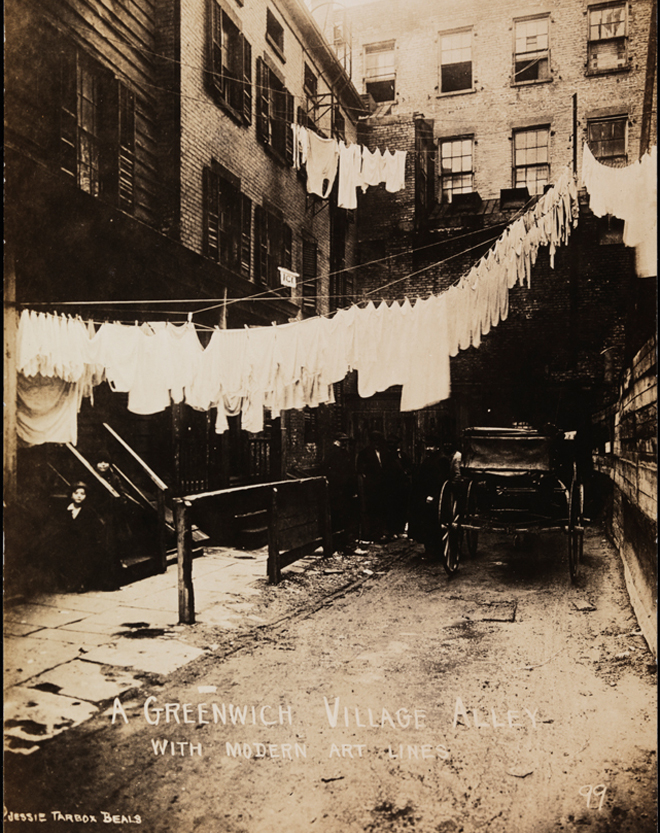

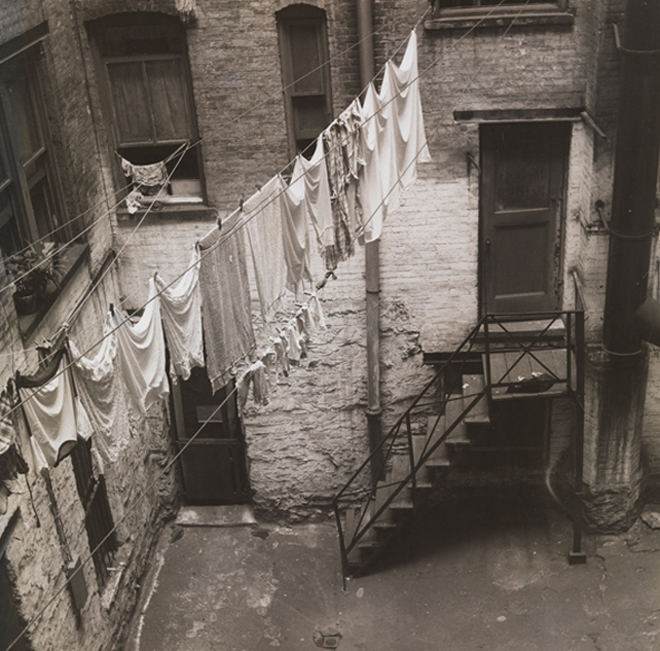

Living in New York City, one becomes accustomed to the grey area between public and private space. Intimate details are exposed through the most mundane daily tasks. Laundry is one of those inevitable rituals that most New Yorkers have to perform in public. Before laundromats, the clothesline was an intrinsic component of the urban landscape. It is impossible to imagine the archetypal tenement building complete without several strands of white linen connecting each structure.

Overlapping in a complex network, each line of garments reads as a household census noting: age, family size, and social status. Bed sheets, undergarments, and women’s hosiery on thin strings allude to bodies not present. Starched white shirts dangle neck-down on tiny tightropes stories high above a precipice of filth-black alleys. A warm summer breeze could bring each garment to life with the weightlessness of guardian angels overlooking the city.

“…they [clotheslines] were useful in many ways besides drying laundry: for running messages and cups of sugar from one apartment to another, or–stretched diagonally down to the ground–for conveying groceries to the elderly infirm or growlers of beer up to the corner saloon. They were characteristic of a life stretched by necessity, out of interiors of apartments as far as possible into the public space beyond.” -Luc Sante

It was inevitable that the City’s great documenters would utilize the presence of the clotheslines as a visual element in depictions of poor and working class neighborhoods. It often added physicality to the frame, serving as a system of measurement of overwhelming heights. Each diagonal line became a symbol of the chaos and intersection of lives and cultures within an imposed vertical grid. The clothing was a recurring character of universal need. The photographer could either promote order or disquiet through composition. At times the wash-line appears uninvited, as unavoidable as a passing vehicle in the corner of the camera frame.

“…Abbott documented this space as a communal laundry line: ropes with pulleys led from apartments to five-story poles imbedded in concrete. Abbott made two exposures, with the laundry and poles forming different abstract configurations. She later recalled that winter day the laundry frozen stiff and the children huddled together, too cold to move (McQuaid, 375).” -Bonnie Yochelson

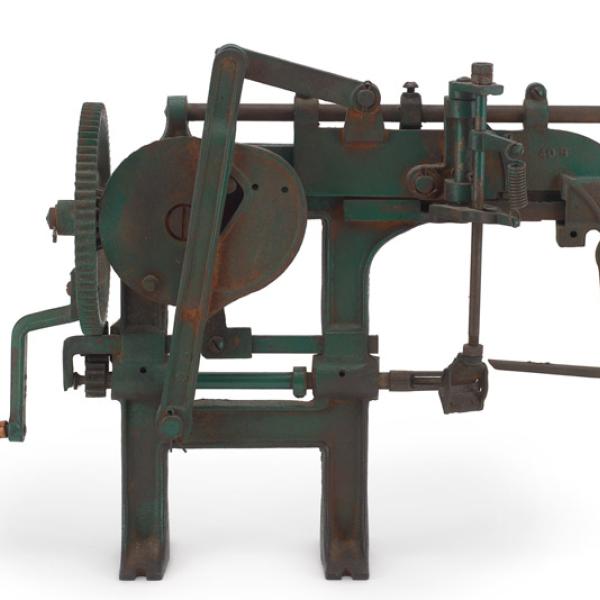

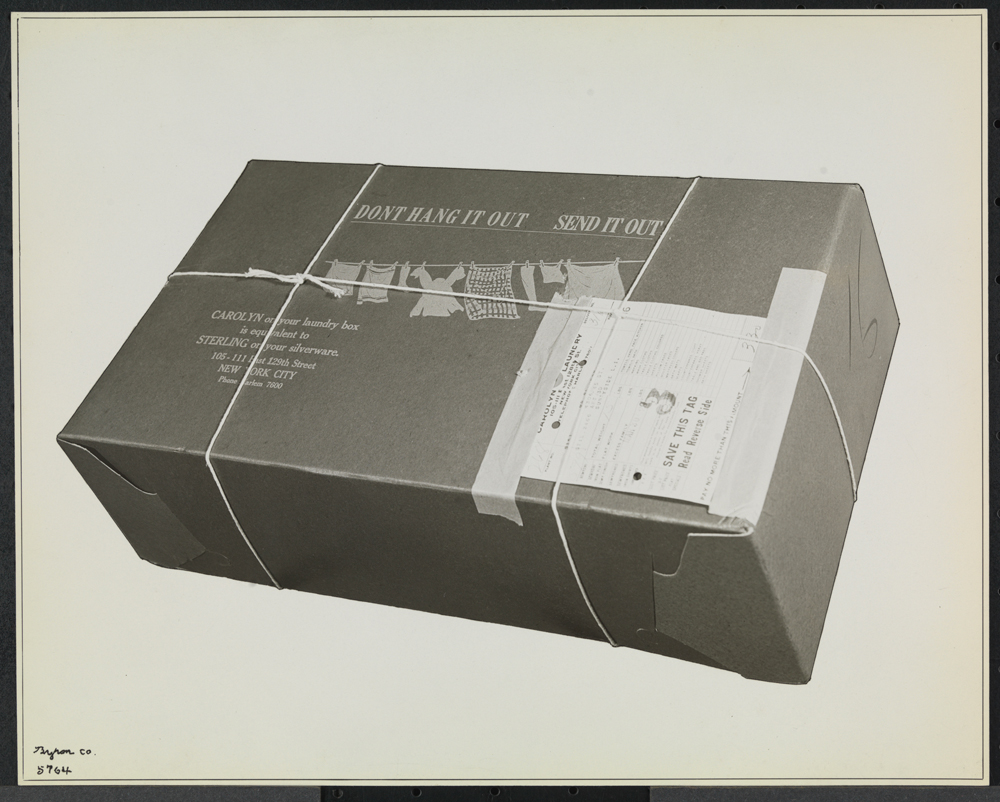

Line drying has largely disappeared from New York as so many traditions of the lower classes in the name of social progress. Industrialized laundries with delivery and drop off were introduced as a convenience service to the middle class at the turn-of-the-century. Electric dryers were developed in the 1930s, but did not become marketable until the late 40s and early 50s. Soon, New Yorkers began to haul their laundry (as most do now) in swollen bags down the narrow passages and steep stairwells of their buildings through the street to laundromats lined with self-service machines and coin dispensers.

Clothesline poles do remain in the five boroughs–frequently as lanky stems shrinking to the base with rust, waiting to be uprooted by landlords. Recently, neighboring communities have gone so far as to outlaw clotheslines for being eyesores (as detailed in the New York Times article “To Fight Global Warming, Some Hang a Clothesline“). Although it is difficult to imagine anything staying clean for long when hung above the city’s streets, in the twenty-first century the poles have taken on new symbolism for environmentalists seeking their resurrection.

Works Cited

Sante, Luc, Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York, Macmillan, 2003.

Yochelson, Bonnie, Berenice Abbott: Changing New York, The Museum of The City of New York, The New Press, New York, 1997.

![Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999). Laundry in Greenwich Village [Women in the laundromat.] 1948. Museum of the City of New York. X2011.4.10875.9E](/sites/default/files/m3y36088.jpg)