The Cross Manhattan Expressway

Object Essay

Monday, November 14, 2016 by

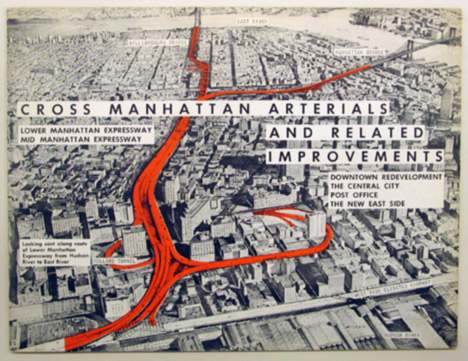

This brochure illustrates a contentious and never-realized future for New York City, its cover showing bright orange lines that represent planned expressways. In 1959, the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, under the control and direction of New York City’s “master builder” Robert Moses, put forth ambitious plans for two expressways crossing Manhattan. These elevated highways would cut through neighborhoods and across the island, connecting New York with its wider metropolitan region. This twelve-page brochure illustrates Moses’ firm conviction that only new multi-lane expressways cutting efficient paths across the island would end congestion in the business districts of Manhattan. Moses was particularly dedicated to pushing the Lower Manhattan Expressway through after another plan for Mid-Manhattan failed.

This was his “last project that would make all the other roads and bridges fit together in perfect harmony,” Anthony Flint wrote in Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took On New York’s Master Builder and Transformed the American City. It was also a way to spark economic development, according to prevailing redevelopment logic: since the area was one of low property values and diminishing tax revenue, clearing it out promised to trigger future improvement through new commercial and residential development, as illustrated by Paul Rudolph’s vision of tomorrow. That logic failed to convince local residents and the anti-redevelopment activist Jane Jacobs. To defeat the Lower Manhattan Expressway, the opposition took on powerful downtown business interests, the Automobile Club of New York, and the city’s construction workers’ union. Fighting it became a cause célèbre, complete with its own protest song, “Listen Robert Moses,” written by Bob Dylan, with Jacobs. Still, working against the car and promoting mass transit and a pedestrian focus was a contrarian notion at the time.

If Moses had been able to execute his vision, the elevated highways would have destroyed vibrant urban neighborhoods in the name of progress, including what we now know as SoHo, the former manufacturing melting-pot neighborhood with its distinctive Cast Iron architecture. Today, this type of massive disruption and displacement seems unthinkable, but at the time it aligned with prevailing notions of what it would take to modernize the nation’s decaying cities. It was the era of the automobile, when, as historian Kenneth T. Jackson has pointed out, ““virtually everyone believed that the private car was the greatest invention since fire or the wheel. Public transportation seemed to be nothing more than a relic of the past.” Wide modern expressways, Moses believed, would save New York as a great city.

The defeat of his ambitious expressway plans marked the demise of Moses’ powerful command-and-control approach to city planning and established a potent mandate for citizen involvement in the planning process. The citizen-led opposition campaign that led to the high-profile defeat of the Lower Manhattan Expressway in 1967 saved the neighborhood of SoHo and triggered a new, broader appreciation for preservation in areas that were of historical significance for cultural and economic reasons. This reversed the traditional directive behind preserving only buildings with architectural merit rooted in elite notions of heritage.

The fight carried a lasting message heard across the nation: cities are for people, not cars. The means by which local citizens in New York were mobilizing to save their neighborhoods became a template in the battle to stop Moses’ proposed alteration of Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. His plan was to run a four-lane roadway straight through the park, which would have destroyed what was and remains a local treasure not only for neighborhood residents, but all of New York. With the Lower Manhattan Expressway out of the way, SoHo emerged as the first historic district in a primarily commercial area. Designated in 1973, its significance was not well understood at the time, but its designation marked a turning point in the evolution of historic preservation in New York and around the country.

Further Reading

- Joseph C. Ingraham, “Mid-City Toll Road Backed by Moses,” New York Times, December 30, 1949, 1, 4.

- Kenneth T. Jackson, “Robert Moses and the Rise of the New York: The Power Broker in Perspective,” in Hilary Ballon and Kenneth T. Jackson, Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York. New York/London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. 67-71.

- Robert Fishman, “Revolt of the Urbs,” in Hilary Ballon and Kenneth T. Jackson, Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007, 122-129.

- Anthony Flint, Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took On New York’s Master Builder and Transformed the American City. New York: Random House, 2009.

- Roberta Brandes Gratz, The Battle for Botham: New York in the Shadow of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs. New York: Nation Books, Perseus Books Group, 2010.

- Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House and Vintage Books, 1961. Also see: centerforthelivingcity.org, a website advancing the observations of Jane Jacobs.

- Yael Friedman, “Paul Rudolph’s Lower Manhattan Expressway”

We asked the author, why is studying history important to you?

The process of building and curating vibrant cities takes place over many decades. Big plans are inevitably contentious, and it is important to understand how they come about, why they succeed or why they fail. The lessons of the past are valuable precursors to wise public policy that aims to advance and enhance urban living.