The Contentious History of Supplying Water to Manhattan

Tuesday, July 16, 2013 by

“

“What made New York a prosperous port – its deep saltwater rivers – made its drinking water lousy. By the middle of the eighteenth century, Manhattan’s water was already infamous: there was too little of it and what little there was tasted terrible.”

-- Jill Lepore, New York Burning (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 135.

”Jill Lepore excellently sums up the dilemma facing colonial New Yorkers in her book New York Burning. But this was a problem of human error over 100 years in the making, dating back to when Europeans first settled in what was to become Manhattan.

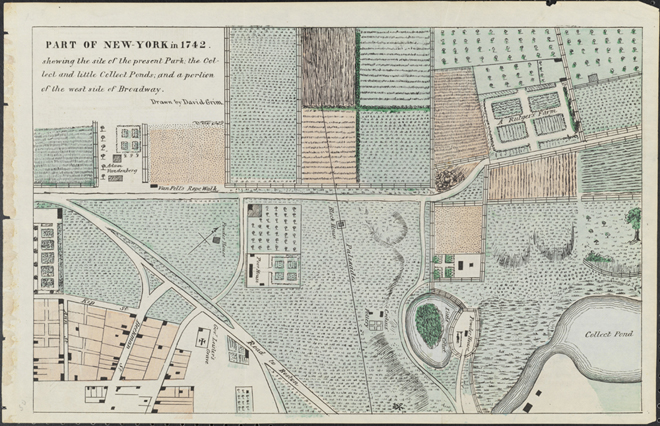

The Lenape tribe had long inhabited the fertile land they called “Manahatta,” meaning hilly island. The land teemed with forests and wildlife sustained by numerous freshwater ponds and streams. In the lower portion of the island was the Fresh Water Pond, situated between today’s Canal and Chambers Streets east of Broadway. The pond was 60 feet deep and spread over 70 acres, with outlets stretching to the Hudson and East Rivers. The native village of Werpoes sat on the pond’s northwest shore, but the Lenape abandoned it after the arrival of the Dutch. Dutch settlers called the pond “kolch,” meaning small body of water. After the English seized New Amsterdam in 1664, the name became corrupted to “collect,” or the Collect Pond. The map below shows the Collect Pond and its inlet known as the “Little Collect”.

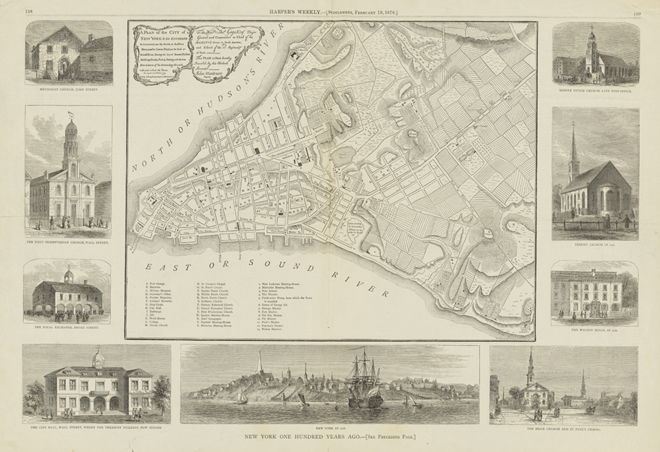

The Collect Pond was far from the populous area of New Amsterdam, however. The Dutch lived behind a timber wall (now Wall Street) extending across the island, built to fend off native attacks that never transpired. People dug shallow wells and collected rain water from cisterns. The map below shows how settlers literally fenced themselves in, away from abundant sources of fresh water.

In July of 1664, the Dutch received word that an English fleet was departing Boston for New York. When the English arrived a month later, staking claim to New Amsterdam, they found a settlement ill-equipped to defend itself – indeed, the Dutch had neglected to supply their fort with water. After the Dutch surrendered without a fight, the English immediately set out building wells, which would supply the city with water for the next two centuries.

Wells suffered from the town’s inadequate sanitary laws and lack of sewers. Waste was dumped on the streets until the city passed a law requiring people to dispose of it in the rivers. At the same time, the town’s increasing population was pushing settlement northward. The once-faraway Collect Pond was polluted by tanneries and other noxious industries that moved into the vicinity. The map below shows just how close the tan yards were to the no-longer Fresh Water Pond.

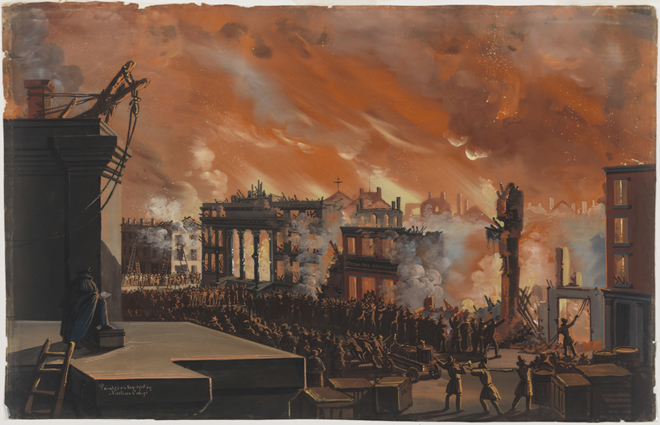

The inability to fight fires was also a constant threat. During the American Revolution, nearly one-third of New York burned to the ground on the night of September 21, 1776, as the British and Patriot armies fought for control over the city. Each side blamed the other for the conflagration, but the fact remained that New York was as woefully unprepared to battle such fires as it was to supply its citizens with fresh water.

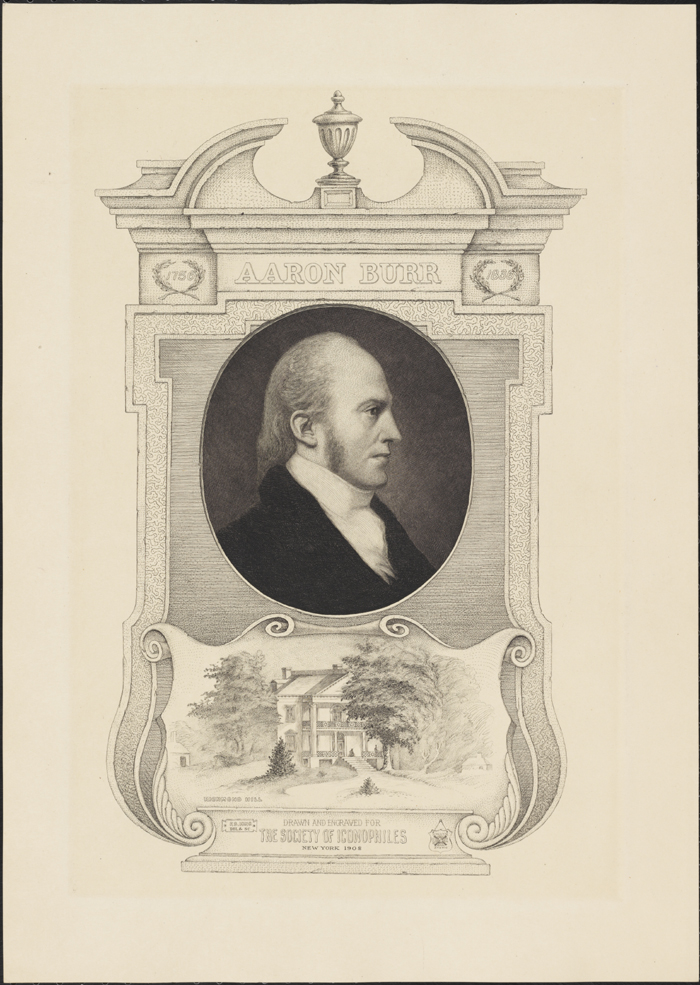

After the revolution, the city suffered yellow fever outbreaks that killed thousands of people and prompted New Yorkers to clamor for a cleaner water supply. Aaron Burr appeared on the scene and offered a solution. Best known today for fatally shooting Alexander Hamilton in a duel, Burr was then a successful lawyer and politician. With his brother-in-law Joseph Browne, Burr proposed a private enterprise, the Manhattan Company, to supply the city with clean water.

Burr worked diligently to gain both Federalist and Republican support for the plan. He even enlisted his future nemesis Alexander Hamilton to convince the city council to consider the bill. As Hamilton promoted the bill to the council, Burr was setting up a company far different from the one Hamilton advocated. Burr’s true motivations for forming a water company were revealed when “An act for supplying the city of New-York with pure and wholesome water” became law. One of the provisions buried deep within the law allowed the Manhattan Company to do whatever it wished with surplus capital, effectively making it a bank and breaking the monopoly of the Federalist-controlled Bank of New York.

The Manhattan Company set about tearing up streets and laying log pipe to make good on its ostensible purpose of supplying the city with clean water. It had installed 21 miles of pipe by the close of 1802 at a total cost of $45,000. Below is part of the original water supply pipe, excavated in 1961 during water main construction at the intersection of Pearl and Fulton Streets. The copper plate was later added to the pipe to make it commemorative, and the pipe was presented to Dr. Merrill Eisenbud in honor of his service as New York City’s first Environmental Protection Agency administrator.

The Manhattan Company system proved to be wholly inadequate, however, as the company focused on banking to the detriment of supplying water. While the company failed to meet its water obligations, it prevailed at banking. Known today as JPMorgan Chase & Co., it is the largest bank in the United States, with assets of $2.3 trillion.

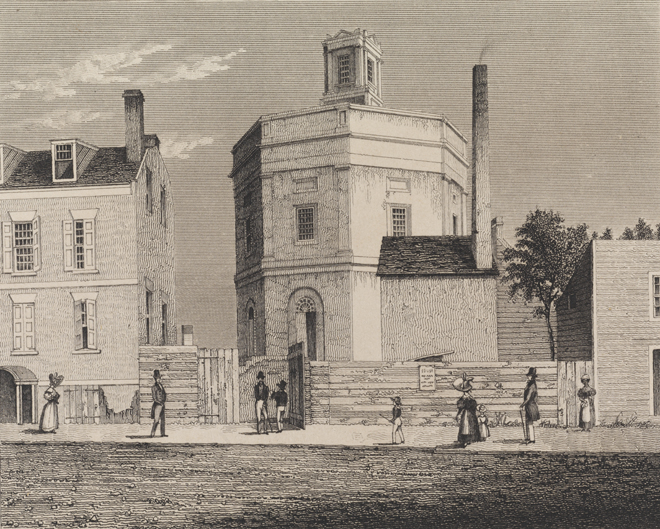

In the meantime, the city continued to languish for want of good water. In 1829, the council decided to build a reservoir at what was then the northernmost edge of the city, near the intersection of Bowery and 13th Street. This waterworks was not intended to provide potable water, but rather to fight fires, which became more of a threat as the city grew. The 13th Street Reservoir officially opened in April of 1831 and was drawn on successfully to put out a fire less than a month later.

The 13th Street Reservoir was an improvement over the Manhattan Company, but city dwellers still had no clean water to drink. Spirits were often added to water to make drinking it tolerable, giving rise to the temperance movement. In 1834, following the devastating cholera outbreak of 1832, New Yorkers voted for a public water supply.

But New York had waited too long. On December 15, 1835, two fires depleted the water supply of the 13th Street Reservoir. A day later, another fire would consume the Merchants’ Exchange as well as most of the other buildings on Wall Street. The Great Fire of 1835 could be seen from Brooklyn. Two people died, a relatively small number given the size of the conflagration, but the loss of property was estimated at $20 million, or around $438 million in today’s dollars.

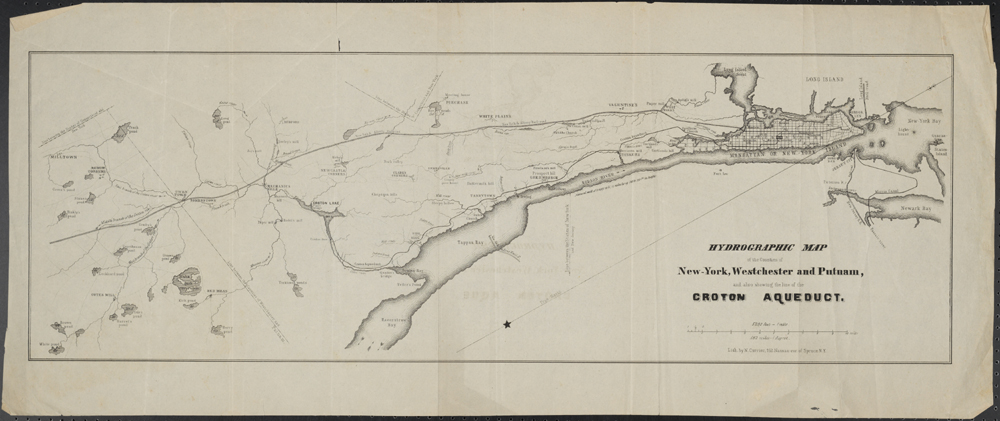

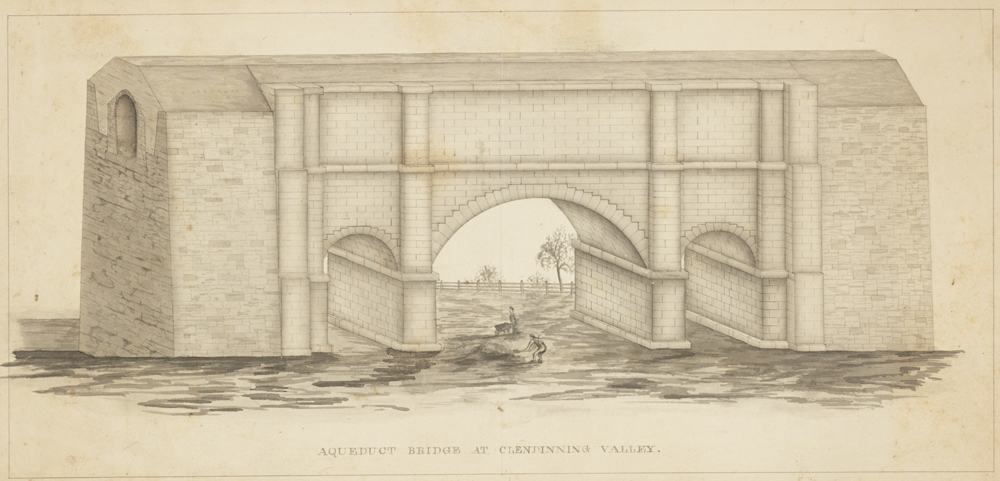

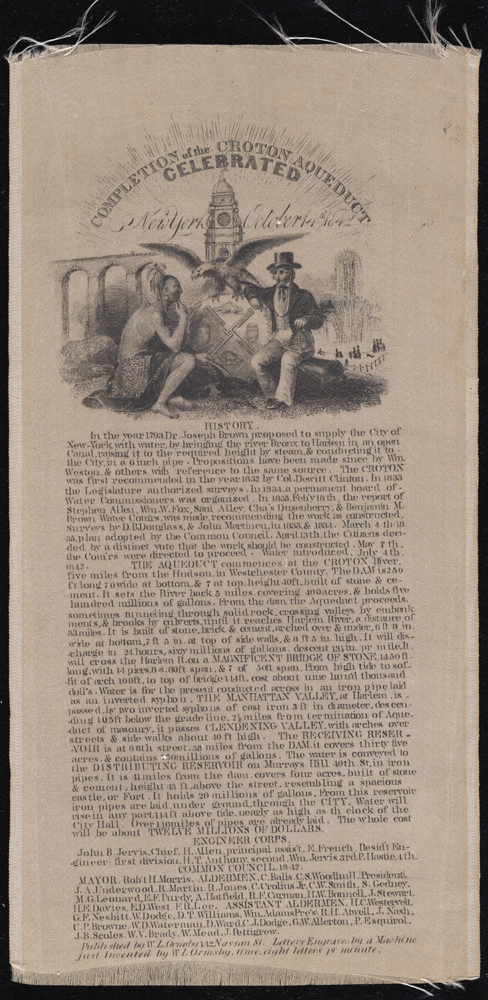

Construction of the Croton Aqueduct began in 1837, five long years after New York City voted for a public water supply. The ambitious engineering project required damming water from the Croton River in Westchester County. Below is a map showing the route of the Croton Aqueduct.

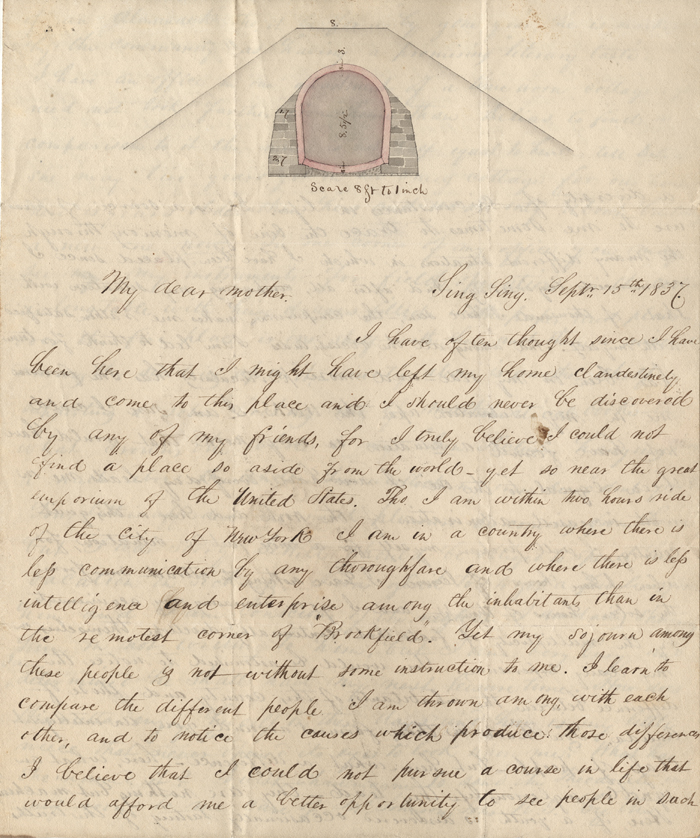

Fayette Bartholomew Tower joined the engineering staff as an assistant and faithfully documented the Croton Aqueduct’s progress in letters and illustrations during his five-year tenure.

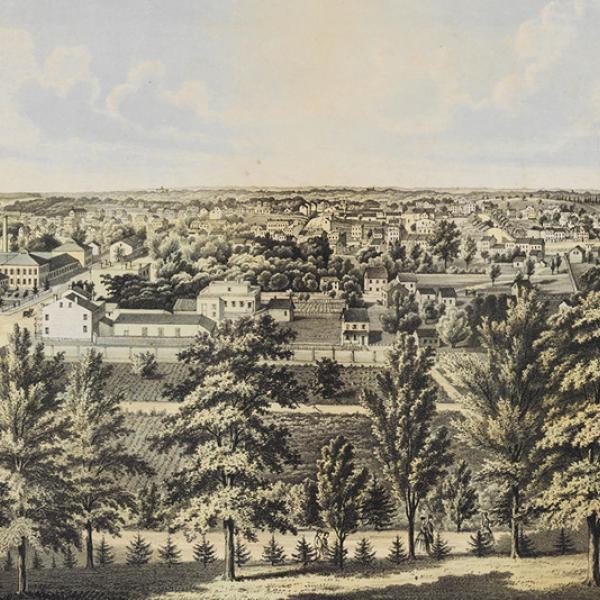

In a letter to his mother, he marveled at the wilderness of Westchester County: “I have often thought since I have been here that I might have left my home clandestinely and come to this place and I should never be discovered by any of my friends, for I truly believe I could not find a place so aside from the world – yet so near to the great emporium of the United States.”

Click here to see the full letter. The Fayette Bartholomew Tower papers at the Museum consist of approximately 160 manuscript letters and 20 discrete objects including books, ephemera and framed documents. Nearly all of the letters are addressed to family members and the bulk of the collection spans the years 1831-1842. Click here to see the finding aid.

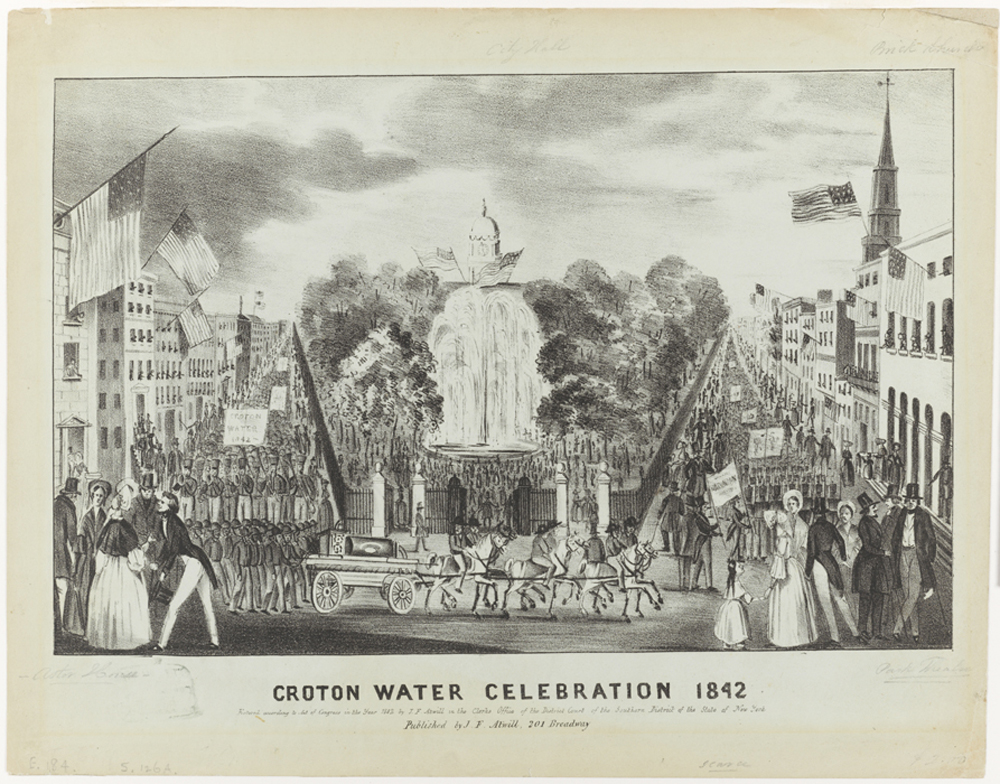

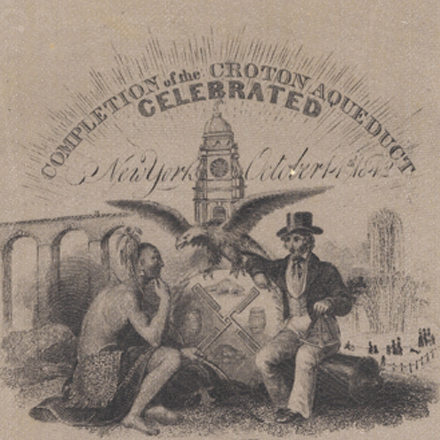

Finally, in 1842, water from the aqueduct began flowing from Westchester County to Manhattan. A daylong celebration was held on October 14 in City Hall Park, with Croton water pumping out of a fountain.

The Croton Aqueduct’s distributing reservoir resembled an Egyptian pyramid and was located where Bryant Park and the main branch of the New York Public Library are today.

The Croton Aqueduct was a resounding success, but could not keep up with population growth. Just forty years after it was built, the aqueduct was becoming obsolete and the city looked further upstate for new sources to meet water demand.

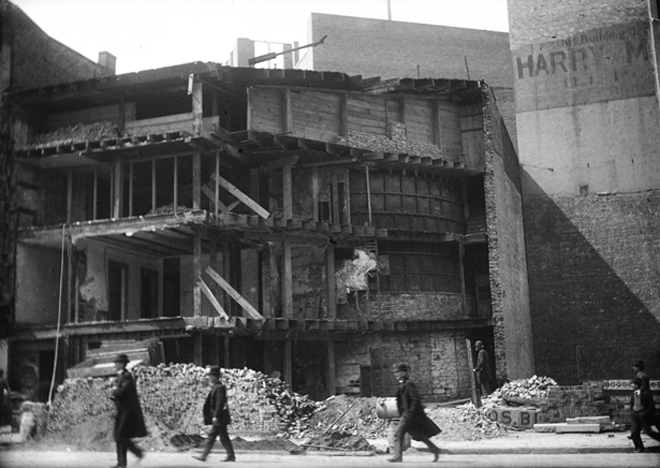

In December 1887, firemen battling a fire at a factory on 25 Centre Street encountered a strange obstacle, a massive iron cylinder about 25 feet tall and and 130 feet in circumference.

What they had found was an 88-year old water tank owned by the Manhattan Company, a forgotten remnant of one ill-conceived attempt to supply the city with water.

Works Cited

Jill Lepore, New York Burning (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005).

Gerard T. Koeppel. Water for Gotham (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).