Commemorating Ten Years of Activist New York at the Museum

Monday, May 2, 2022 by

May 2022 marks ten years of the Museum’s ongoing exhibition Activist New York. The show opened on May 3, 2012 in the newly endowed Puffin Foundation Gallery for Social Activism, and it has displayed a rotating array of stories about activist histories in New York City—from 17th-century struggles over who could live in the Dutch colony of New Netherland to the Movement for Black Lives—ever since. This anniversary offers an occasion to look back at the origins and evolution of the exhibition, and to think about exhibiting activism itself, which we describe as “New Yorkers mobilizing around issues they believe in.”

The path to Activist New York was part of the Museum’s decade-long renovation, which at its completion in 2015 had completely modernized the 1932 building at 1220 Fifth Avenue. As part of this effort, the Puffin Foundation generously endowed the new gallery and the idea for Activist New York was born. Meanwhile, staff and advisors debated how to organize the show. Should it be chronological or thematic? How many stories could we tell? How many objects could we show? Chief Curator Sarah Henry, Curator Steven H. Jaffe, and the curatorial team settled on 14 case studies and 250 objects and images spanning centuries, mediums, and the political spectrum.

Activist New York was intended to change over time. Since I arrived at the Museum as the Puffin Foundation Curator of Social Activism in 2014, we have changed ten of those case studies, sometimes more than once! We have also rotated countless objects into the show, accessioning some of them into our collection. It can be a challenge to keep adding new content to an exhibition, but also an opportunity to assess and improve. We’ve added new media installations, installed new vivid wayfinding, broadened the array of voices and stories, and honed in on the seven major themes of the show that content falls under: immigration, religious freedom, political and civil rights, gender equality, economic rights, environmental advocacy, and global issues.

The content I’ve been most proud to add not only broadens the range of diverse and marginalized activist voices through images and objects, but involves collaboration and community members. In 2017, with co-curator Christopher P. Harris, we installed a new final section on the Movement for Black Lives in consultation with activists, and updated this content again in 2020. Official planning conversations with lifelong activists and community members shaped new sections on the Young Lords and trans activism in 2019. Most recently, I worked closely with activists and artists to include a sampling of objects relating to activism today, from masks to food takeout containers from mobilizations during the pandemic. Even a new section on laundry workers in Chinatown and beyond in the 1930s turned out to be about connecting with the community—often grandchildren or other family members whose grandparents worked in Chinese hand laundry businesses. As Activist New York has reaffirmed, the past is never past, and activism isn’t either.

The exhibition also extends beyond gallery walls. The Museum held 50 Activist New York public programs over the past decade, with over 5,000 people in attendance. An online version of the show launched in 2016, and features all exhibition content and case studies past and present. Crowd-sourced images of protests, meetings, or other activist forms that use the hashtag #ActivistNY appear in the gallery and are share on the Museum's social media channels. A companion book by Steven H. Jaffe, Activist New York: A History of People, Protest, and Politics, was published by NYU Press in 2018 and will soon be available online for free to teachers. Education has been a major component of Activist New York: the show is the most-requested field trip to the Museum and has served 85,000 students, teachers, and chaperones. The education team has also offered 24 lesson plans and more than 125 programs for teachers to enhance—and according to feedback “transform”—their teaching of these complex topics in the classroom.

To celebrate the tenth anniversary of the show, the Museum commissioned the Brooklyn-based artist Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya to create Raise Your Voice, an immersive installation in the anteroom next to Activist New York that examines harassment of the city’s Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities, illuminates alliances between AAPI and black New Yorkers such as Yuri Kochiyama and Malcolm X; Aand finally invites audiences to answer questions Phingbodhipakkiya poses in the installation through QR codes. What do you stand for? What will be your legacy? These questions, and others, get at the heart of Activist New York: to ask New Yorkers to voice what they believe and will mobilize for, and to illuminate stories of New Yorkers before them in order to connect the past with the present—and see where we go from here.

Explore images from the Activist New York exhibition—past and present.

New York artist Keith Haring created designs used in anti-AIDS campaigns, including the posthumously printed image at the top of this 1991 GMHC dance-a-thon flyer. He also founded the Keith Haring Foundation in 1989 to assist AIDS-related and children’s charities. Haring died of AIDS-related illness in 1990.

Image Info: Gay Men's Health Crisis, 1991, Museum of the City of New York, Mark Ouderkirk Collection, X2011.12.133.

As the nation’s hub of manufacturing, mass marketing, and advertising, New York became a center for woman suffrage-related memorabilia. Activists distributed a wide array of lapel buttons, armbands, pennants, badges, and song sheets to raise money and publicize their cause.

Image Info: 1910s, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Mrs. Edward C. Moen, 49.215.12.

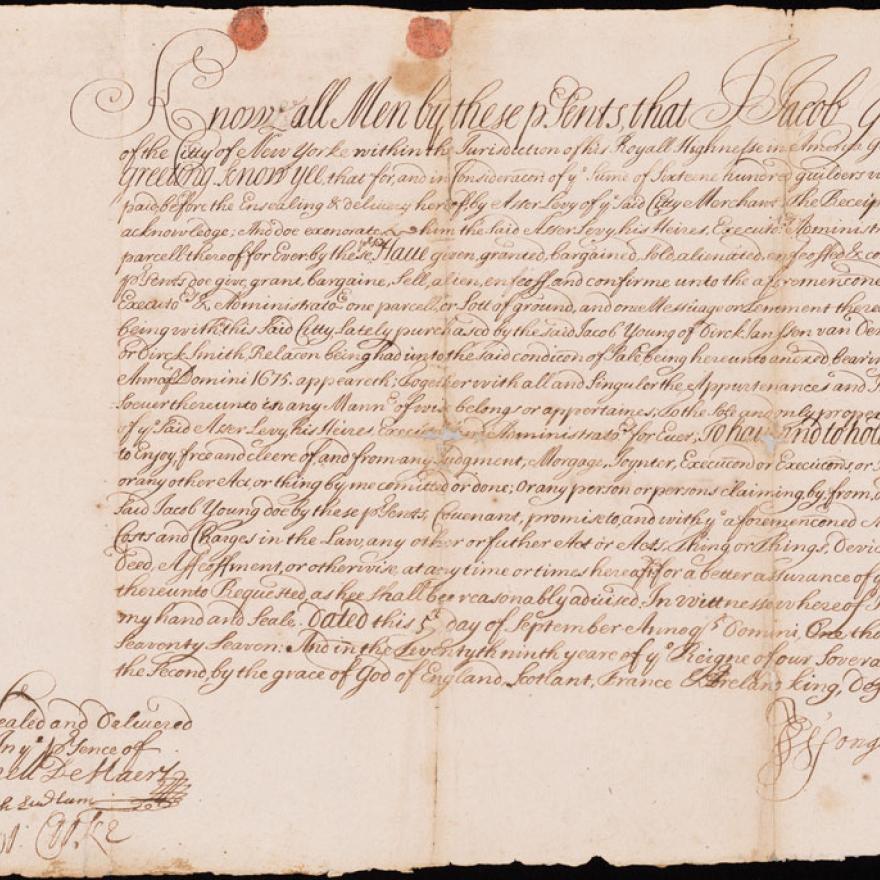

Twenty-three Jewish refugees from Brazil and two European Jewish merchants arrived in New Amsterdam in 1654. Colony Director-General Peter Stuyvesant wanted to turn them away, complaining of “their deceitful business towards the Christians.” The Company ordered Stuyvesant to let them remain and enjoy the same rights they would have in the Dutch Republic, and Asser Levy became the first Jewish person to own property in the colony.

Image Info: September 5, 1677, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Mrs. Newbold Morris, 34.86.1.

The shirtwaist, a mass-produced blouse marketed in a variety of styles and prices, became enormously popular in the late 19th century. Made in New York factories, the shirtwaist symbolized the “New Woman,” freed from restrictive traditional garments and ready to participate in a widening array of public activities, including wage labor and union activism.

Image Info: Gray and white striped cotton with linen collar, ca. 1895, Fisk Clark & Flagg, E.A. Morrison & Son, 898 Broadway, New York, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Mrs. John Hubbard, 41.190.22.

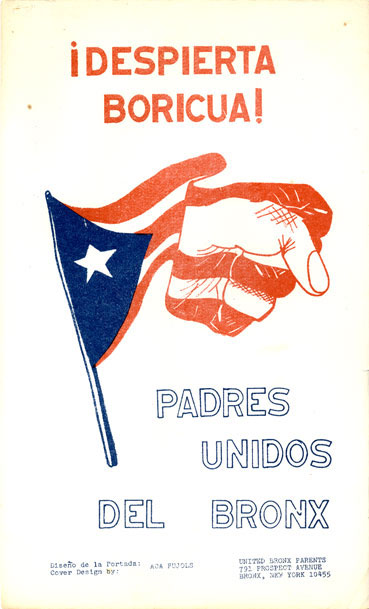

United Bronx Parents was founded by Evelina López Antonetty in 1965 as an education reform organization focused on mobilizing Puerto Rican parents and children. By the 1980s, the group also provided a range of services and programs to the South Bronx community.

Image Info: United Bronx Parents, 1967, Courtesy the United Bronx Parent Records, the Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY.

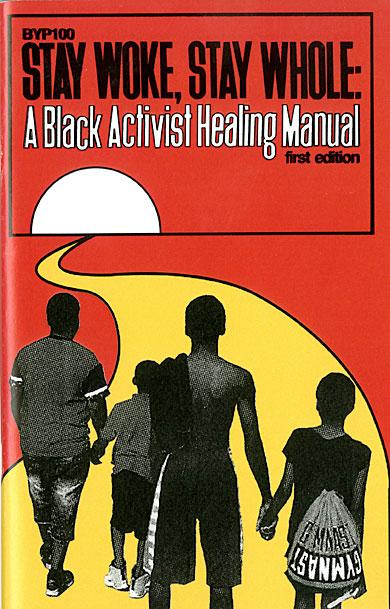

Space for self-care and healing have become central components of the Movement for Black Lives. These initiatives intend not only to create safe spaces and new restorative modes of activism, but also to address the physical stress of racism and the disproportionately poor health outcomes of people of color.

Image Info: Black Youth Project 100, Cover by Fresco Steez, 2017, Courtesy Chris Harris.