Charles T. Harvey: Elevating Transit in 19th-Century New York City

Thursday, April 16, 2020 by

Although the phrase "traffic jam" is a byproduct of the automobile age—apparently coined around the year 1908, and making its first New York Times appearance in 1916—the concept of immovable, insurmountable traffic was already a painfully vivid one for mid-19th century New Yorkers. "Broadway is fast becoming impassable and unmanageable," the Times complained in a piece titled "City Locomotion" in 1860. In the western hemisphere's most populous and densely crowded city, horse-drawn omnibuses (predecessors of the modern city bus), streetcars, private carriages, wagons, and pedestrians faced daily gridlock that was so severe, the Times claimed, that it "renders it a work of great difficulty for foot passengers to cross it [Broadway] at any point below Eighth-street."

How to solve New York City's traffic problem, especially the ordeal of travel along Manhattan’s avenues connecting uptown and downtown? One newcomer to the city, Charles T. Harvey (1828-1912), devised an answer. A self-taught engineer and inventor from Connecticut, Harvey made his reputation working on a shipping canal between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. He then devoted himself to railroad construction and founded the village of Harvey, Michigan. Then as now New York City had a magnetic effect on ambitious entrepreneurs, and in 1865 Harvey sold his railroad interests and came to New York.

Once relocated, Harvey found that he was not alone in trying to find ways of speeding New Yorkers through the city. Other ambitious inventors, planners, and visionaries proposed solutions that never reached fruition. The opening of London's underground railway in 1863 inspired some to seek an answer beneath Manhattan's busy streets, but they were ultimately blocked by politicians, powerful landlords fearful of disruptions to their street-level property, and financing problems; New York City would not get a subway system until 1904. Others looked upward, suggesting an array of rapid transit networks (some of them quite fanciful) to be built on trestles in the empty spaces above the major thoroughfares. Even the corrupt Tweed Ring got into the act, backing a plan for an ambitious "Viaduct Railway"-- which if built would have generated financial kickbacks and other graft that was the Ring's lifeblood. Again, opposition, costs, engineering challenges, and inertia blocked these plans.

Alfred Ely Beach, publisher and editor of Scientific American magazine, secretly built a one-block-long tunnel for a pneumatic train under Broadway, but aboveground property owners helped block its expansion. Subterranean mass transit in New York would have to await the opening of the subway in 1904.

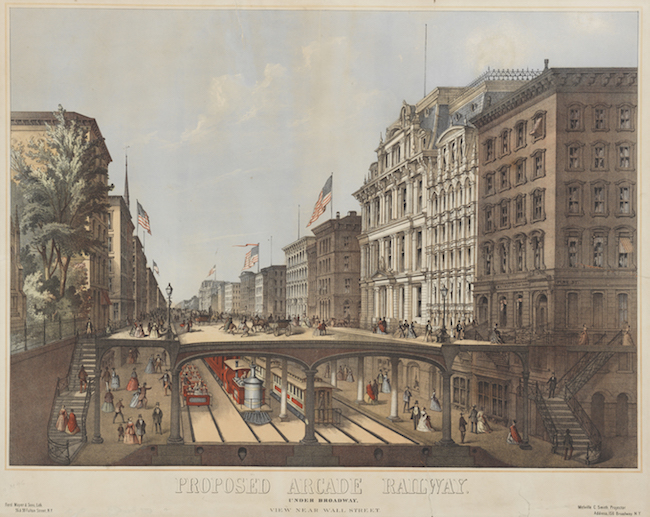

New York's governor vetoed an ambitious plan for an "Arcade Railway" on Broadway that would have displaced horse-drawn vehicles and foot traffic to a new platform high above the street. This print shows what the system might have looked like if built.

A moving platform-- as in this proposal for "Speer's Endless Traveling or Railway Sidewalk"-- would have allowed travelers to stroll or ride in special chairs above the traffic.

During the 1850s, engineer James Swett proposed to hang passenger cars below steam locomotives in an early vision for an elevated railway.

It was Charles T. Harvey who managed to surmount such obstacles to design and build the world's first elevated street railroad on Manhattan's West Side. His elevated railway, with train cars pulled by cables, was no less experimental than other proposals. The world’s first entirely elevated railway had opened in London in 1836, but it had been constructed on a brick viaduct rather than above an existing and functioning roadway. In 1867, on an elevated track erected over lower Manhattan's Greenwich Street, Harvey demonstrated the viability of vehicular traffic on rails supported by an iron superstructure thirty feet above the street and sidewalk. By 1868 a cable-driven test line ran for about half a mile on Greenwich Street, although it was not accepting passengers.

In June 1870, the world's first elevated street railroad finally opened to passengers. It had only two stops, at Dey and Greenwich Streets and at the Hudson River Railroad Terminal on 29th Street and Ninth Avenue. Even so, Harvey’s cable-driven design was problematic: the cables broke frequently, forcing stranded passengers to reach the street by ladder. The accident-prone company failed within months, the railroad gave up its cable cars for steam locomotives, and Harvey was pushed out of the company he founded.

Yet from Harvey's initial vision sprang a successful and growing system. By the mid-1870s, steam-powered elevated railroads, built and operated by private companies, were expanding rapidly in the cities of New York and Brooklyn. By the early 1890s, the Manhattan Elevated Railway Company (which controlled the island’s elevated trains) was carrying nearly 197 million passengers a year, while Brooklyn's lines carried over 30 million passengers.

As for Charles T. Harvey, his story ends on an exasperating note. Harvey went back into the railroad business as a chief engineer before returning to New York and beginning a long, ultimately unsuccessful effort to win compensation from the state for having invented the elevated railroad. He died in Manhattan in 1912, age 83. One can only imagine his mixed emotions every time he peered skyward to see the fruit of his ingenuity carrying thousands of daily passengers to and fro above the city's major avenues.

Indeed, for generations of late 19th- and 20th-century New Yorkers, the "el" (short for "elevated") was a defining reality of city life. As one of the transit systems knitting the metropolitan area together, elevated trains (along with ferries, trolley lines, and bridges) literally made the growth of the city possible by enabling commuters, shoppers, and others to travel between their homes and distant destinations. The consolidation of Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island into the five-borough Greater New York City in 1898 was plausible in part because mass transit made the larger city imaginable as a coherent social, political, and economic organism.

At the same time, the train trestles and tracks of the elevated lines were a defining architectural landmark of the city, a fixture of daily life as well as a feature in popular culture. The novelist William Dean Howells vividly described riding the "el" in A Hazard of New Fortunes (1889), while fans of the original 1933 movie version of King Kong will remember Kong derailing a Sixth Avenue Elevated train before climbing the Empire State Building.

Yet for many, the gloomy shadows of the tracks, the noise of the trains, the smoke and ashes scattered by locomotives before the lines switched to electricity, and the invasion of privacy occasioned by passing riders glancing through the windows of second- and third-floor apartments all dampened enthusiasm for the system. As early as 1870 the New York Herald condemned Harvey's "crude contraption" by claiming that it "violates all the principles of engineering and all natural laws besides. Let it therefore be done away with at once." Later, the writer Stephen Crane described one of the Bowery's elevated train stations with its "leglike pillars" as resembling "some monstrous kind of crab squatting over the street."

Affluent residents of some avenues were able to use political influence and lawsuits to keep their neighborhoods clear of elevated trains; working-class tenants of other districts were not so lucky. After 1904 when the subway became an alternative reality, and as more and more New Yorkers owned automobiles, criticisms gained further ground. The Great Depression decreased ridership, and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia proposed to raise property values, commerce, and employment on the avenues below the tracks by removing the lines. Between 1938 and 1955 Manhattan's lines were torn down, but in the outer boroughs there are still 156 miles of elevated track as part of the subway system. Taking a ride on one of these aboveground trains is still a great way to see much of the city-- and to recall a time when millions of people rode in the sky above New York's streets.

Image Credits:

[Image 1:] Thomas Benecke, Sleighing in New York, 1855. Museum of the City of New York, 45.271.1.

[Image 2:] James Blaine Walker, Fifty years of Rapid Transit, 1864-1917, c. 1918. The Law Printing Company via Archive.org.

[Image 3:] Old state lock 50 years ago, c. 1905. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., LC-DIG-ppmsca-17297.

[Image 4:] Under Broadway – Interior of Passenger-Car, in The Broadway Pneumatic Underground Railway, 1871. Museum of the City of New York. 42.314.142.

[Image 5:] Ford, Mayer & Sons and John M. August Will, Proposed Arcade Railway under Broadway near Wall Street, 1869. Museum of the City of New York, 29.100.2400.

[Image 6:] Alfred Speer's Moving Sidewalk, 1871. Public Domain.

[Image 7:] Swett's Proposed Elevated Railway -- for Broadway, c. 1855. Museum of the City of New York, 74.104.

[Image 8:] Charles T. Harvey, first experimental elevated railroad, 1867. Museum of the City of New York, X2010.11.14495.

[Image 9:] Elevated Railroad, c. 1875. Museum of the City of New York, 56.89.2.

[Image 10:] William Louis Sonntag, Jr., Bowery at Night, c. 1895. Watercolor, 13 x 17 4/5 in.; Museum of the City of New York, 32.275.2.

[Image 11:] Charles M. Marvin, Elevated Railway Map of New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City, c. 1880. New York Public Library, 5056892.

[Image 12:] Third and Westchester Avenue, 1891. Museum of the City of New York, X2010.11.7084.

[Image 13:] Edmund Vincent Gillon, Looking west on 34th Street at the demolished Third Avenue El, c. 1955-179. Museum of the City of New York, 2013.3.1.941.