Beyond the Numbers: The 2020 Census and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Thursday, April 9, 2020 by

The enumeration conducted by the census offers a high-resolution view of the United States population. But beyond that, the census itself as a process offers a glimpse into conditions in the country at the moment the counting takes place. The questions it asks, the labels it uses to refer to groups of people, the conditions under which the enumeration actually occurs, the statistical methods and tools used for the counting after enumeration, the reactions by individual states to official results: it all reflects wider and important socio-economic, political, and even philosophical trends in the country and our city.

In 2020, the census is being conducted mostly online—a significant change after decades of households mailing their self-reported answers. Responses to the census are to reflect household situations as of April 1, 2020 (Census Day). However, on that specific date, New York City was under a lockdown order due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Schools and non-essential businesses were shuttered, hundreds of New Yorkers were unemployed, and many dying in a tragedy of stunning proportions. Given this pandemic context, how might the current COVID-19 crisis be reflected in the 2020 census? The impact could be felt not just in terms of the hard numbers, but also in the level of participation and the time it takes to process the data, among other factors.

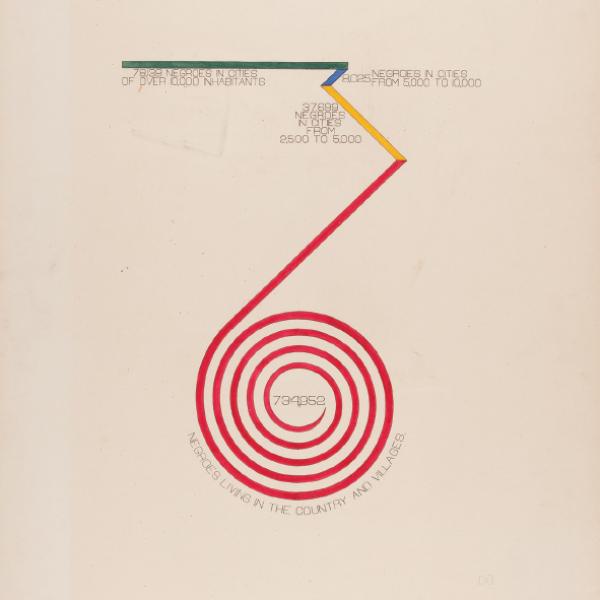

This idea of the census-as-mirror of wider societal context is as old as the census itself. Consider, for example, something as fundamental to the history and identity of the country as the institution of slavery. The infamous “Three-Fifths Compromise” (Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the US Constitution) can be understood as a set of special instructions about how to weigh the human beings enumerated in the census for purposes of taxation and political representation. It is interesting to see how this clause affected enumerations during the period. Enslaved people were recorded individually as the enumerator found them in each household; but they were subsequently counted as three-fifths (60 percent) of a human being, not as full persons. While at the country’s founding northern delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia had objected to the counting of enslaved people at all in the proposed federal census, southern white slaveholders won a significant but partial victory. Tallying three-fifths of each enslaved person translated into a larger number of pro-slavery southern congressmen who would be able to sit in the new House of Representatives, thereby claiming a larger share in controlling national policy. It also gave southern states considerably more electoral votes in presidential elections than they would have had if only free people had been counted.

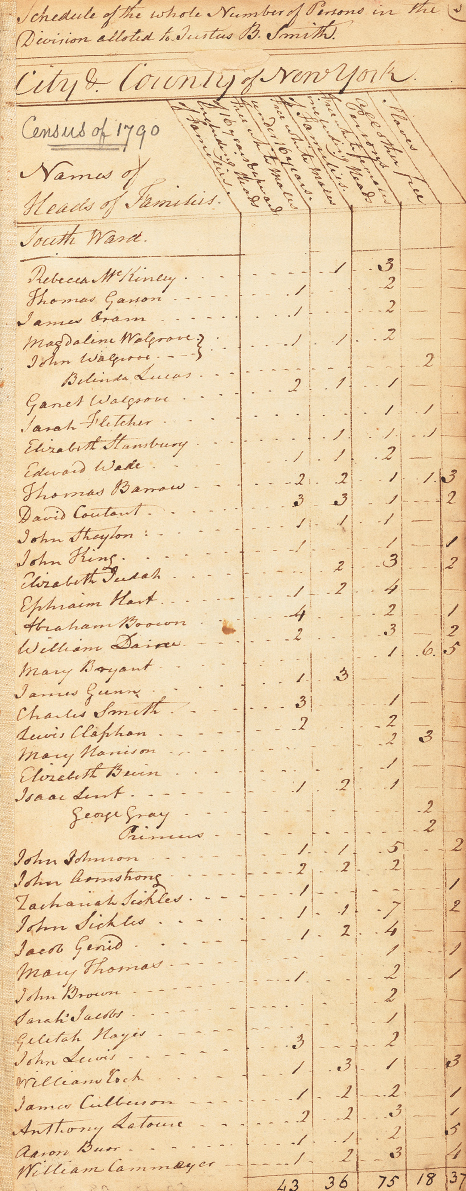

As an example, towards the bottom of this page of the 1790 census, we can see specific numbers for the New York City household of Aaron Burr, the third vice president of the United States. The census shows that there were four free persons living with Burr, and that he also owned five enslaved human beings; meaning that a majority of the people living with Burr were enslaved. This is the actual number and condition of the persons living in his household; we know this thanks to the census. However, the political, economic, and social system of the time then proceeded to count those five enslaved persons as three persons, denying all of them of their full personhood. Another way to think about it is that in the specific case of Burr’s household, the Three-Fifths Compromise expunged and denied the very existence of two enslaved persons. Even though the Three-Fifths Clause was concocted to satisfy white southerners, it also applied in New York, where slavery continued until 1827, and elsewhere in the north where slavery still existed when the Constitution was drafted in 1787.

As it pertains the US census, this state of affairs persisted until the last enumeration before the Civil War, that of 1860. Ironically, 1860 is the first time Native Americans were officially counted (provided they had renounced “tribal rules”). Between the 1860 and 1870 enumerations, the United States went through a devastating Civil War (1861-1865); and once again, the census reflected the momentous changes brought about by this fratricidal conflict, in which slavery was the main casus bellis. The 1870 census is the first in which African Americans we recounted as full persons, and as a result, the first that allows us to see—however incompletely—the conditions of African-American life throughout the country. The census was one of the ways in which African Americans were granted legal personhood in the United States. And, perhaps just as significantly, the Census has been one of the few institutions in which the rights of African Americans have never been successfully rolled back. Ten years later, during the 1880 Census, women were allowed to work as enumerators for the first time, reflecting wider social trends about the role of women in American society. These are general examples of how the larger process of the Census, and not just the data we can obtain from its enumeration, offer us a glimpse into wider and profound societal changes at specific points in American history.

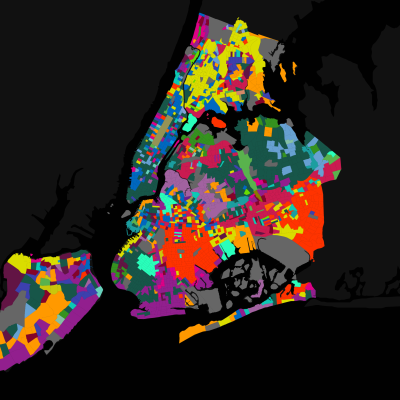

Yet, for New York City, we need to remember that the most salient characteristic in our relationship with the federal census has been an ever-present concern that the city’s population is being undercounted. Indeed, since the first national census in 1790, New York City has regularly contested the official count offered by the federal government, claiming a larger population than the federal government has attributed to us. The negative impact of an undercount in terms of political power and federal monies is significant.

On many occasions, the City and State have questioned census results in court through lawsuits. In the 19th century, New York State actually even decided to conduct its own state census to have more accurate numbers about the demographics of its own population. This New York State Census was mandated by the State’s constitution and conducted every ten years, starting in 1825, until it was abolished in 1931 as a result of the financial hardships of the Great Depression: another example of how the context around an enumeration process reflects larger societal trends.

How is the 2020 census going to reflect the current COVID-19 context? How will the exceptional circumstances under which the census is occurring in a locked-down New York City affect us for the next ten years? Will New Yorkers ignore the constitutional mandate to respond to the census given the stress and general disruption of the present moment? Or, alternatively, will New Yorkers respond in greater numbers than usual precisely because some are locked down at home, presumably bored, and with not much to do? Will we see marked differences in participation—more than usual—between those areas of the city where residents can generally stay home during the lockdown, and those areas where they are generally required to go to work? What are future historians and researchers going to see of COVID-19 in the 2020 census as it relates to New York City?

The answers to all those questions remain to be seen. But we are not passive characters in this story; we are active agents of historical change. Fill out the Census. Encourage other New Yorkers to do so. One thing is clear: we should not allow the virus to determine our collective future. The pandemic has already taken too much from us; let us fight back by letting our numbers be fully counted. That is, after all, who we are: brave New Yorkers.

1. Page from the United States federal census for New York’s South Ward, 1790. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29.

2. Clockwise from left: “Department Fails to Adjust Census to Reflect Our Minority Population,” by Peter L. Zimroth, Newsday, May 2, 1988.

“Learn How to Count, Feds Warned,” by Bob Liff, Newsday, December 20, 1989.

“‘Non-Census’ Dave & Mario: Undercount Is Part of an Anti-Urban Plot,” by Richard Steier, New York Post, August 30, 1990.

Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives. Photo: Brad Farwell/Museum of the City of New York.

3. New York City police census, 1890. Courtesy NYC Municipal Archives. Photo: Brad Farwell/Museum of the City of New York.

Monxo López is the Museum of the City of New York's Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Post-Doctoral Curatorial Fellow. Dr. López assisted in curating the current exhibition Who We Are: Visualizing NYC by the Numbers.