New York Now: Living Room

Living Room

ANTI-EVICTION MAPPING PROJECT

Narratives of Displacement and Resistance (NDR), 2022

COURTESY OF THE ANTI-EVICTION MAPPING PROJECT

The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP) is a nation-wide housing justice collective founded in 2013 that uses technology and storytelling to build tenant power in anti-gentrification movements. The AEMP’s Narratives of Displacement and Resistance (NDR) traces the personal and social histories of tenants in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. For New York Now, the AEMP’s New York City chapter has updated the map with new eviction data and tenant stories. The interactive map points are amplified by audio clips from oral histories that speak to COVID-19’s ongoing impact on struggles for housing justice in BIPOC, poor, and working-class communities across New York. Printed ephemera highlights their work engaging tenant organizing movements throughout the city.

ARIANA FAYE ALLENSWORTH

1. Staying Power: Michael and LaGuardia Houses poster, 2021

2. Staying Power: Public Housing Signs of the Lower East Side and East Village poster, 2022

RISOGRAPH PRINTS

Ariana Faye Allensworth is a New York City-based participatory artist, designer, and researcher, interested in spatial justice and belonging. Her creative practice “explores stories of Black homemaking and world-building and the ways that folks have… ‘made a way out of no way.’” Copies of Allensworth’s Staying Power zine highlight lesser-told stories about public housing and the lived experiences of its residents. Allensworth is a longtime member of the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP), a housing justice collective that uses technology and storytelling and whose work is also on view in this gallery.

NOLAN TROWE

1. Cold Lampin’ On the A, January 2018

2. It All Seems to Fade Away, Too Fast, October 2017

3. The Helium Lightness of It All, April 2019

4. Do or Do Not, There’s No Try, February 2018

5. “That’s My Favorite Picture, Man,” April 2019

6. Nothing Can Separate the Love, June 2019

7. Fuck the MTA, Homie..., January 2018

8. My People, November 2017

9. The World is Yours, The World is Yours, April 2019

10. Community, Just Community, February 2018

11. ROC, February 2019

12. Secrets We Share, June 2019

From the series “Adopted Family”

GELATIN SILVER PRINTS

For a diverse major US city with 8.5 million people, New York City is profoundly inaccessible to people with disabilities, especially wheelchair users. Despite the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA), which goes widely unenforced, many transit systems, schools, cultural institutions, and jobs remain inaccessible, which increases people’s social isolation. Access to social services remains complicated and inadequate for working-class people and those living under the poverty line. Inherent inaccessibility and ableism add an additional barrier for people with disabilities.

After a spinal cord injury in 2016, multidisciplinary artist Nolan Trowe committed himself to documenting his chosen family of New Yorkers—his found community. The “Adopted Family” series tells a nuanced story, one that does not dwell in pity or sentimentality. Audiences see the joy found from playing in pickup basketball leagues and taking boxing classes, the immense struggles of taking public transit, and the daily work of raising children and caring for family. This series shows the interconnectedness of all life and strives to create empathy, regardless of disability.

ANDERS JONES

1. Bodega #1

2. Bodega #2

From the series “Bye, Buy Bedstuy,” 2022

PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLAGE

Anders Jones is a multi-disciplinary artist based in New York whose work uses a variety of disciplines to uncover and expand the potentials of materials as a means to explore social commentary.

For his series “Bye, Buy Bedstuy,” Jones uses the corner store, or bodega, as the focal point for his observations of the gentrification and cultural disregard of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. His photographic assemblages ask: what happens when the tapestry of a neighborhood transforms over time? For Jones, “The bodega corner store acts as an entry point to explore feelings of disorientation and periods of destabilization felt by long standing residents of a community (who often get left behind). Through the use of photography, printing techniques, assemblage, textile design and abstraction, the series orients viewers within a kaleidoscopic use of color to conjure a therapeutic empathy and/or a purely formal relationship to the work.” Jones’ work is symbolic of the importance of local businesses to maintaining a sense of place and home.

JAMEL SHABAZZ

1. Father and Son, New York City, c. 2003

2. Black in White America, Brooklyn, 2010

3. Showtime, Brownsville, Undated

ARCHIVAL PIGMENT PRINTS

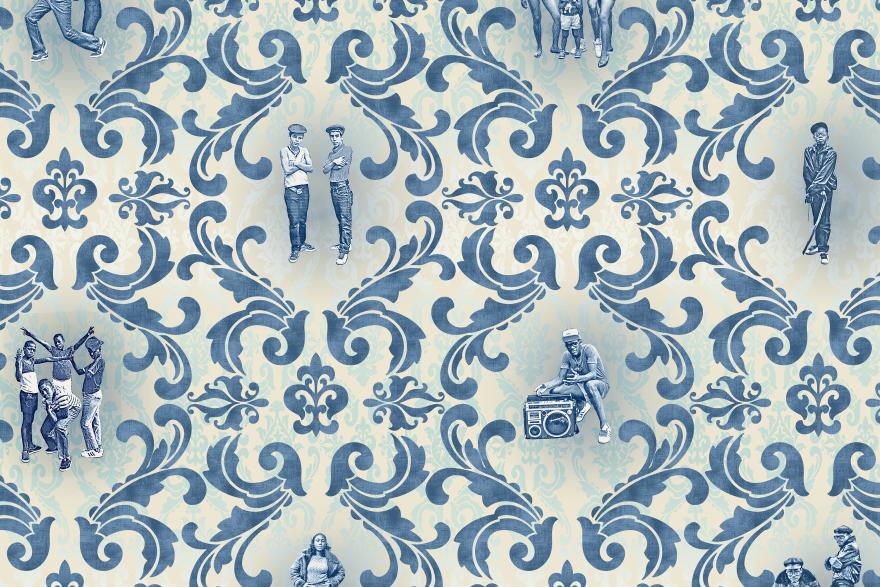

JAMEL SHABAZZ AND ETHER AND EARTH BY ANDERS JONES

Back in the Days, 2022

WALLPAPER

Jamel Shabazz was born and raised in Brooklyn. He began photographing his friends and family at the age of 15. After a stint in the military, Shabazz returned to New York City in 1980, where he witnessed hope and possibility, followed by the emergence of the crack and AIDS epidemics, and then the war on drugs. Amidst these cultural shifts, he took to the streets with his camera.

His work reflected contemporary attitudes and prevalent fashions within Black and Latinx communities and revealed communities able not just to face struggle, but to thrive. The resulting images have since become a celebrated kind of family album. Selections of these images are the centerpieces of the wallpaper, a collaboration with artist and designer Anders Jones.

The three portraits on view depict contemporary residents of Brooklyn and the photographer’s ongoing commitment to community building in the face of gentrification in neighborhoods like Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, and Flatbush. They reflect the hopes, dreams, and resilient culture of his community.

ALAN CHIN

1. Unknown studio photographer

Cuba, 1929

GELATIN SILVER PRINT

ALAN CHIN: “Sing Chin (陳東成) was the older brother of my paternal grandfather who I never met because he died during WWII. Sing left our village of Gongmei in Toishan County, Guangdong Province (江美 台山 廣東) in 1927, and lived for seven years in Cuba before arriving in the United States after a harrowing voyage hidden in the coal hold of a steamer. Like many Chinese immigrants of his generation, he claimed that he was born in California but that his documents had been destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire. He became a partner in a storefront laundry in Bayside, Queens, retired in 1964, and moved to Manhattan’s Chinatown where he lived for the rest of his life. This photograph from his sojourn in Cuba is the oldest photograph in my family’s possession.”

2. Alan Chin

New York, March 1990

GELATIN SILVER PRINT

AC: “Chu Kam Ying (朱金英, left) was my paternal grandmother. She was the longest lived of 10 children, and of the first generation of women in our family not to have bound feet. She emigrated to Hong Kong in 1951 and to the US in 1974. Jennifer Chan (right) is her great-granddaughter, born in and visiting from the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan, 10-years-old at the time. Kam Ying could speak only the Hoisanva variant of Cantonese and Jennifer only English, so they didn’t have a language in common. Their conversation was limited to simple greetings.”

3. Unknown studio photographer and Fow Sang Chin

Toishan, China and New York, 1951–1952

GELATIN SILVER PRINT

AC: “When my father Fow Sang Chin (陳阜生, right) arrived in the US, the only photograph he had of his wife Mee Kuen Chin (陳林美娟, left) was an ID-card size portrait. His assumed identity as a paper son was that of a single man, so she was in none of the photographs of his ostensible family that he had to share with and submit to the American immigration authorities. Before he received any of the photographs that she would send him over their next 19 years of separation, he made an enlargement of the tiny print, and framed it next to one of himself as a newly arrived immigrant at Rockefeller Center in midtown Manhattan.”

4. Gosia Wieruszewska

New York, December 30, 2018

CHROMOGENIC DEVELOPMENT PRINT

AC: “My daughter Hannah Derbes Chin, not quite 5-years-old, on my shoulders in Greenwich Village.”

5. Unknown photographer

Hong Kong, March 22, 1951

GELATIN SILVER PRINT WITH INK

AC: “My father Fow Sang Chin (陳阜生, second from the left in the front row) was already using his paper son name of Doo Gawn Chin (陳子官)— the fictional identity that he had to memorize as the “son” of an already-resident Chinese American with American citizenship. His wife—my future mother—Mee Kuen Chin (陳林美娟, second from the right in the back row) isn’t standing next to him; public displays of affection were not encouraged in their generation. Many families documented these farewells at airports with photographs—they knew that they might not see each other again for many years—or ever.”

6. Waa Dou Photo Studio

Hong Kong, 1966

GELATIN SILVER PRINT / MODERN PRINT

AC: “From left to right, my sister Siu Yin, my maternal grandmother Ching Kam Chan (陳請金), my brother Bonlap Chan (陳本立), my paternal grandmother Kam Ying Chu (朱金英), and my mother Mee Kuen Chin (陳林美娟). This is the only photograph I have of my two grandmothers together. My maternal grandmother lived in Malaysia and I met her once in 1989— and this photograph was made on the second of her only two trips to visit her daughter in Hong Kong. Note that her maiden name was Chin (Chan), and she married a Lam, and her daughter, my mother, married a Chin. Considering the distance between their respective villages, the relationship would be quite distant—branches separated many generations before. It wasn’t customary in traditional China for women to change their names upon marriage so I have gone with what my grandmothers themselves used. My mother adopted the Western/American style and used her husband’s surname so I’m going with that as well.”

7. Unknown studio photographer

Toishan, January 1948

GELATIN SILVER PRINT

AC: “The wedding photograph of my parents Fow Sang Chin (陳阜生, left) and Mee Kuen Chin (陳林美娟, right). They were married the day after my father’s 19th birthday, after meeting only once before. as was customary in traditionally arranged marriages. The farming villages that they came from were about four miles apart, and were just recovering from WWII’s ravages of Japanese military occupation, famine that killed far more people than combat, and the destruction of the only railroad in the region. They lived together in Toishan for less than three years before my father’s emigration to the US and my mother’s to Hong Kong. That separation would last 19 years. The Chinese Confession Program enabled my father to reclaim his true identity and the Hart-Celler Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 ended the last vestiges of the Chinese Exclusion Act, allowing them to finally reunite.

8. Fow Sang Chin

New York, 1971–1972

CHROMOGENIC DEVELOPMENT PRINT

AC: “My mother Mee Kuen Chin (陳林美娟, left) arrived in New York City in 1970, rejoining her husband, my father, who ran and lived in the back of a storefront laundry in the Williamsbridge neighborhood of the Bronx. I was the first one of our family born in the United States, a year later in 1971 (right). My father was an avid photographer and photographed our family extensively. Accidental double-exposures were both possible and common on film, with unpredictable results. In this case the roll of film was exposed and then reloaded by mistake.”

9. Corky Lee

New York, August 1971

GELATIN SILVER PRINT

AC: “Pioneering Chinese American photographer Corky Lee (李揚國) photographed my great uncle Sing Chin (陳東成, right) getting his blood pressure checked at a Chinatown Health Fair in Columbus Park. The fair was organized by volunteers who created the Chinatown Health Clinic (now called the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center) to provide free and low-cost medical care to the historically underserved Chinese American immigrant population.”

10. Alan Chin

New York, May 2011

GELATIN SILVER PRINT

AC: “My mother Mee Kuen Chin (陳林美娟) at home a few months before her death from endstage renal disease. She had been a seamstress, and my father a pattern layer and shop steward, in Chinatown sweatshop garment factories for over 20 years until their retirements. Neither ever earned much more than the minimum wage. She did receive a modest union pension in addition to Social Security, and through chain migration they each sponsored the emigration to the US of both their sisters and their extended families.”

A Chinese American Family Album: The First Century, 2022

PAPER AND INK

Alan Chin’s book and photographs reflect his family history. He says, “When the first Chinese immigrants came to the US in the 19th century, they came searching for gold, built the first transcontinental railroad, and established communities in cities across the country. But the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and other racist laws meant that for decades, only a trickle of new immigrants could continue to come to America, excluding most women. Like my family, most of those Chinese immigrants originated in southern China, in a four-county area centered around Toishan.

To show oneself to family that may not be seen for decades—or ever again—studio photographs were mailed across oceans. The photographs were one of the only tangible, tenuous, links that families could maintain at great distances. As the era of popular photography began in earnest with the near-global postwar boom, even poorer families could afford simple snapshot cameras.

ARIANA FAYE ALLENSWORTH

Staying Power: Vol. I, 2022

PAPER AND INK

RAMONA JINGRU WANG

Family Album, 2021

NEWSPRINT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

In American popular culture, the Asian subject has long been stereotyped as many contradictory things: forever foreign, inscrutable, exotically beautiful, and dangerous. Ramona Jingru Wang’s Family Album is a quiet refusal of such representations, instead creating images of Asian diasporic people that defy easy categorization.

As an artist and model, Wang has deeply considered the role that photography plays in exploiting Asian models and creating flat narratives. The Family Album, printed on newsprint, challenges what we think or see by blurring the boundaries between private family snapshots and commercial fashion photography. The photographs show intimate scenes at home between Asian people who may be family members, lovers, or friends, but could also be strangers. The project asks: are these family photos any less authentic if the subjects are professional models, or if the photographer is visible in the frame? For Wang, the act of making photographs itself can become an act of familial care by creating intimacy and shifting perceptions.

Image Credit: Jamel Shabazz and Ether and Earth by Anders Jones, Back in the Days, 2022. Courtesy of the artists.