Let Us Stay

The Struggle for Religious Freedom in Dutch New Netherland

1650-1664

Ongoing

Back to Exhibitions

In 1657, 31 settlers in the Dutch colony of New Netherland (now New York and New Jersey) risked arrest and banishment when they spoke up in defense of members of the Society of Friends—known as Quakers—who had been banned from the colony. Insisting on their right “to do good unto all men,” these residents of Vlissingen (today’s Flushing, Queens) offered shelter to Quakers despite the disapproval of Director-General Petrus Stuyvesant.

First settled in 1624, the increasingly diverse colony was, by the 1650s, the site of numerous struggles over religious rights. After Stuyvesant became Director-General in 1647, the colony fined, arrested, and attempted to banish not only Quakers, but also Baptists and Jews.

Yet religious minorities and their supporters fought for the right to remain in the colony, to worship openly, and to hold property. The Quakers successfully challenged Stuyvesant by petitioning the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam, which managed the colony, to be allowed to stay and practice their faith, placing them among the earliest activists in New York’s history.

After the English gained control of the colony in 1664, these groups stayed on and enjoyed new liberties in what was now New York. Although Catholic worship was still against the law, members of many different Protestant groups arrived and stayed. By the early 1700s, Manhattan’s Jews could worship openly, vote, and serve on juries.

Through grassroots activism, religious minorities helped establish a city that would become a refuge for immigrants from across the Atlantic world.

Meet the Activists

Asser Levy

Asser Levy

Asser Levy was one of two Jewish merchants who arrived in New Amsterdam from Amsterdam in 1654. Levy petitioned the Dutch West India Company for the right of Jews to serve in the town militia, practice trade, and own property. He ultimately joined the “burgher guard” that protected the colony and signaled citizenship, and also became the first Jewish person to own property. In the years after the English gained control of the colony in the 1660s, and after repeated petitioning, Jews in New York enjoyed legal, civil, and economic rights that were still denied to them in many parts of Europe.

Image Info: Alex Shagin, 1999, Courtesy Jewish-American Hall of Fame.

John Bowne

John Bowne

In 1662, five years after the Flushing Remonstrance, Peter Stuyvesant banished to the Netherlands John Bowne of Flushing, an English-born Quaker, for hosting religious gatherings in his home. Bowne protested to the Dutch West India Company, which in 1663 instructed Stuyvesant to moderate his policy. “Allow everyone to have his own belief,” the directors wrote to him, “as long as he behaves quietly and legally.” Bowne returned to Queens, where he remained a Quaker leader until his death in 1695. His activism helped extend protection to the colony’s other religious minorities.

Image Info: Scribner’s Monthly, May 1881, Courtesy Indiana University.

Objects & Images

Niew Amsterdam Op T Eylant Manhattans

Niew Amsterdam Op T Eylant Manhattans

The Dutch colony of New Amsterdam was established over 1625 and 1626. Based on a rendering from 1653, this is one of the earliest views of the city—what is now the Southern tip of Manhattan—under Dutch colonial rule.

Image Info: ca. 1700, Museum of the City of New York, The J. Clarence Davies Collection, 29.100.1572.

Petrus (peter) Stuyvesant

Petrus (peter) Stuyvesant

The Dutch Republic was unrivaled among European countries for its toleration of religious minorities. But, as director general of the New Netherland colony, Petrus Stuyvesant believed that social order depended on strictly controlling the young settlement’s religious life. Stuyvesant and his allies feared that religious dissenters threatened government authority and might turn New Netherland and its capital, New Amsterdam, into “a receptacle for all sorts of heretics and fanatics.”

Image Info: Susan Rivington Stuyvesant (after Hendrick Couturier), no date, oil on canvas, Courtesy The New-York Historical Society, bequest of Gerard Stuyvesant, 1922.99.

Dutch Tobacco Box

Dutch Tobacco Box

This Dutch brass and copper box, used to hold tobacco, dates from the 1600s. In addition to the crucifixion scene depicted on the lid, an image of Christ kneeling is engraved on the box’s underside.

Image Info: 17th Century, Museum of the City of New York, 41.36.1.

Dutch Tin-glazed Tile Fragment

Dutch Tin-glazed Tile Fragment

This Dutch ceramic tile fragment illustrates the crucifixion of Christ. Many tile fragments were excavated, as part of the South Ferry Terminal Project, along what is now the southern tip of Manhattan.

Image Info: Earthenware tile with tin glaze decoration, 17th Century, Courtesy the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation/New York City Archaeological Repository, 15768.427.1.

Quaakers Vergadering.fronti Nulla Fides (the Quakers Meeting)

Quaakers Vergadering.fronti Nulla Fides (the Quakers Meeting)

In the mid-17th century, Quakers were considered dangerous radicals in Protestant England and the Dutch Republic. Quakers did not have ordained ministers—anyone could preach—and religious services were collectively led, all of which threatened the Dutch Reformed Church’s assumptions about the importance of hierarchy and social order that were the foundation of the link between church and state in New Netherland.

Image Info: No date, Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-ppmsca-04598.

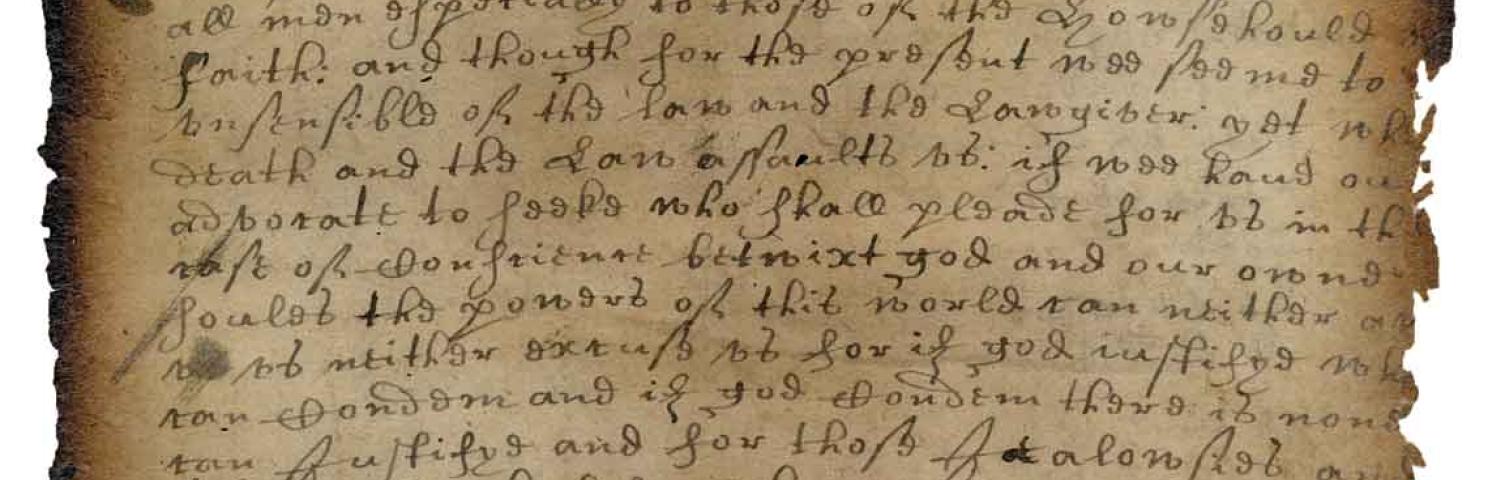

Flushing Remonstrance

Flushing Remonstrance

In 1657, 31 residents of Vlissingen (today’s Flushing, Queens) signed a petition against Director-General Peter Stuyvesant’s ban on Quakers. “If any of these said persons come in love unto us, we cannot in conscience lay violent hands upon them,” they wrote. Now considered pivotal to New York’s heritage of civil and religious rights, it had no immediate impact at the time—beyond the jailing of four signers.

Image Info: Courtesy New York State Archives, 1657.

Bowne's House

Bowne's House

John Bowne’s house became a landmark in American Quaker history and a symbol of the early struggle for religious freedom in New Netherland. One of the city’s few surviving 17th-century buildings, the house is now a museum. This postcard is modeled on an 1825 lithograph by Charles Etienne Pierre Motte.

Image Info: Artvue Post Card Co., ca. 1955, Museum of the City of New York, Postcard Collection, F2011.33.1467.

Deed By Which Asser Levy Purchased Property From Jacob Young

Deed By Which Asser Levy Purchased Property From Jacob Young

Twenty-three Jewish refugees from Brazil and two European Jewish merchants arrived in New Amsterdam in 1654. Colony Director-General Peter Stuyvesant wanted to turn them away, complaining of “their deceitful business towards the Christians.” The Company ordered Stuyvesant to let them http://www.achaten-suisse.com/ remain and enjoy the same rights they would have in the Dutch Republic, and Asser Levy became the first Jewish person to own property in the colony.

Image Info: September 5, 1677, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Mrs. Newbold Morris, 34.86.1.

A View Of Fort George With The City Of New York From The Southwest

A View Of Fort George With The City Of New York From The Southwest

This 18th-century view of the English colonial city of New York shows the legacy of earlier battles for religious toleration. Even though the Church of England became the colony’s established church when England seized New Netherland from the Dutch in 1664, the new government continued and then broadened the rights of diverse Protestant sects and Jews. Here, one can see the spires of different churches on New York’s skyline.

Image Info: ca. 1740, hand-colored lithograph, Museum of the City of New York, Bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair in memory of Mr. and Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 52.100.30, John Carwitham.

Key Events

| Global | Year | Local |

|---|---|---|

| 1609 | Henry Hudson claims New York for the Dutch East India Company | |

| 1624 |

First European settlers arrive in what is now New York |

|

| 1625 | Dutch colony of New Amsterdam established on Manhattan Island | |

| Kieft’s War between Dutch colonists and Lenape Indians | 1640 |

A new charter promises “freedom of conscience” but confirms the Dutch Reformed Church’s monopoly on public worship Kieft’s War between Dutch colonists and Lenape Indians |

| 1647 | Petrus Stuyvesant appointed Director-General of the Dutch colony | |

| 1654 | The first Jewish settlers arrive and petition for the right to stay |