The Long Fight for Educational Equity in NYC

Thursday, February 11, 2021 by

Over 65 years after the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case ruled school segregation unconstitutional, New York City’s schools are still some of the most separate and unequal in the country. The following post draws on the information presented in an educator workshop hosted by the Museum of the City of New York in the fall of 2020, which explored the role of education activism in the Civil Rights Movement and connected that history to the youth-led movement for educational justice in the city today.

The Long and Ongoing Fight for Education Equity in NYC

Almost a decade after the Brown ruling, New York’s Urban League shared some startling statistics. In an Amsterdam News article entitled “More Jim Crow Schools Than We Had Before!,” the paper reported that from 1955 to 1963, the number of racially segregated elementary schools in New York City had increased from 42 to 119, with similar growth rates for junior and high schools. [1] In the era of Brown, when schools in the South were told to desegregate “with all deliberate speed,” New York’s schools became more segregated and unequal.

Since courts ruled the type of segregation that existed in the North and West to be “de facto” (in fact) segregation, as opposed to “de jure” (by law, like in the Jim Crow South), the city had no legal obligation to rectify it—or even admit there was a problem. Yet the mechanisms that produced this “de facto” segregation were far from accidental or natural. Housing policy, education policy, and the private actions of white families all led to a highly unequal school system. The fight to overcome this educational segregation became a key front in the Civil Rights Movement as it played out in the urban North, and it remains an ongoing battle to this day.

An array of New Yorkers confronted school segregation in the 1950s and 1960s, building on a longstanding emphasis on education in the Civil Rights Movement. Ella Baker, chair of the NAACP’s education committee in the 1950s, partnered with Black and Puerto Rican parents and school administrators to document conditions in their local public schools—an approach in line with her belief in the importance of empowering everyday people to create change in their communities. Using tools like the “Check Your Schools” questionnaire seen below, parents and administrators collected information on school facilities, resources, demographics, and academic achievement levels, collecting data that attested to the existence of deep-seated racial segregation and poor conditions in the schools attended by New York’s students of color. Activists and parents brought this data directly to the Board of Education to advocate for change, despite the Board’s denial that school segregation was a problem.

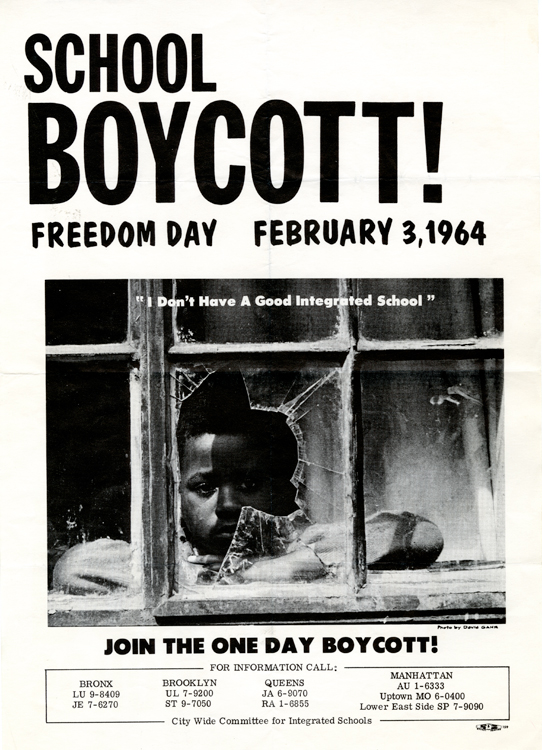

Education activism also sparked what, in 1964, became the largest civil rights mobilization in U.S. history before the June 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. Under the leadership of civil rights leaders Bayard Rustin and Rev. Milton Galamison, and their Puerto Rican allies Manny Diaz and Gilberto Gerena Valentín, over 460,000 students and teachers stayed out of school on February 3, 1964—known as “Freedom Day"—marching across the Brooklyn Bridge and demanding “complete desegregation of all schools.”

While great momentum for desegregation existed following the boycott, activists also faced significant resistance. Just one month after Freedom Day, a group of 10,000 white parents, organizing as Parents and Taxpayers (PAT), held a competing march across the Brooklyn Bridge opposing school pairing and busing plans intended to promote racially integrated schools.

“

When 10,000 Queens white mothers showed up to picket at city hall against integration, it was obvious we had to look for other solutions.

”

- Doris Innis, Harlem Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) member, 1971 [2]

In the face of these obstacles, activists turned to other strategies to achieve educational equity and liberation as well. By the late 1960s, education equity activists, frustrated by the lack of progress in integration, increasingly pushed for “community control” over New York City schools—calling for local neighborhoods to assume oversight over administrative hiring and curricula. This push for community control was accompanied by lobbying for bilingual and bicultural (what today we might call “culturally responsive”) education from Puerto Rican activists and educators. Led by figures like Antonia Pantoja and Evelina López Antonetty, Puerto Rican activists demanded that the Board of Education respond to the needs of the city’s growing population of Puerto Rican students, who by 1970 comprised 22% of the public school population as increasing numbers of Puerto Ricans moved from the island to the mainland United States in the post-World War II era. [3]

With the support of Mayor John Lindsay and funding from the Ford Foundation, three city school districts were decentralized in 1968, with community-elected governing boards taking greater authority over hiring and instruction. The city’s public school teacher’s union, the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), opposed decentralization however, and after an Ocean Hill-Brownville administrator fired 13 UFT teachers from one of the decentralized schools, the union went on strike, shutting down the city’s public schools for over a month. What would come to be known as the Ocean Hill-Brownsville teachers’ strike brought an end to community control in New York and fractured coalitions between Jewish and Black activists in the Civil Rights Movement.

Though New York’s experiment in community control was short-lived, activists’ demands for curricula that included Black and Latinx history and culture, and teachers who came from the communities they taught, went to the heart of the issue for educational justice. As activist and public school parent Mae Mallory noted, for many within the Civil Rights Movement, the effort to end school segregation “had nothing to do with sitting next to white folks.” Rather, all of these efforts—for integration, community control, and bilingual-bicultural education—shared the same end goals: an end to racism, the right to self-determination, and the guarantee of equal opportunity for children of color.

Today, 83% of Black students and 73% of Latinx students in the NYC public school system attend a school that is 90% nonwhite, while 34% of white students attend a school that is over half-white.

Ella Baker and Milton Galamison would likely be dismayed that the fight for school desegregation lives on, over 65 years after Brown and 55 years after the ’64 boycott. Yet they would likely also be proud to see the spirit of their activism alive and well in today’s young activists. Organizations like Teens Take Charge, Integrate NYC, and Black Lives Matter at School are at the forefront of the current movement to desegregate NYC’s public schools. Led by students themselves, these groups have held boycotts, launched innovative social media campaigns, and advocated for concrete policy changes like abolishing “screened” admissions policies and repealing the Hecht-Calendra Act, a 1971 state law that bases admission to New York City’s elite public high schools on an entrance exam activists argue unfairly excludes Black and Latinx students.

Sharing the long history of activism for education equity with students can serve many functions. For one, it helps students understand how the Civil Rights Movement played out in the North—often in their own neighborhoods across New York City—and introduces them to lesser-known movement leaders like Mae Mallory, Bayard Rustin, and Antonia Pantoja. Crucially, these stories also allow students to see themselves and their communities as key actors in history, with the power and agency to fight for the change they wish to see in their schools and city.

Bring the history of New York City education activism to your classroom or community with the following resources:

The Museum of the City of New York’s exhibition Activist New York traces 400 years of social activism in New York City and includes the story of civil rights in New York City from abolition to #BlackLivesMatter. The gallery and its virtual complement feature the stories of Ella Baker, Milton Galamison, and the 1964 School Boycott. Find primary sources, historical context, and lesson plans at activistnewyork.mcny.org.

MCNY Lesson Plans, complete with primary sources for student inquiry, include a lesson on civil rights that examines Ella Baker’s education activism with the NAACP and the 1964 School Boycott (“We Shall Not Be Moved: New York and Civil Rights, 1948-1964”) and a lesson on labor rights that discuss the 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville Teachers Strike and community control movement (“City of Workers, City of Struggle: Civil Rights and Union Rights”).

We’ve created a resource list on the topic of education equity in NYC that includes helpful reading and listening suggestions related to the history of and ongoing fight for equal schools in NYC. Check it out here.

Book our virtual field trip The Civil Rights Movement in NYC for your students! Hear the stories of Civil Rights activists, learn about New York’s major role in the Black Freedom Movement, and discuss the ongoing movement for racial justice today. Learn more and submit a request here.

Notes:

[1] Sara Slack, “More Jim Crow Schools Than We Had Before!” New York Amsterdam News, December 14, 1963.

[2] Tomas Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (New York: Random House, 2008), 467.

[3] John Shekitka, “On Arrival: Puerto Ricans in Post-World War II New York,” Columbia University Teachers’ College Center on History and Education, August 16, 2017. https://www.tc.columbia.edu/che/whats-new/from-the-archives/on-arrival-puerto-ricans-in-post-world-war-ii-new-york/