Getting Dressed: Gilded Age Afternoon Dress

Thursday, February 7, 2019 by

One of the most rewarding aspects of the ongoing assessment of the collection of women’s garments at the Museum has been the opportunity to “flesh out” these objects. In a literal sense, we dress each object three-dimensionally on a mannequin padded out to match the proportions of the garment. This aspect of that process is amply demonstrated by the timelapse video of curator Phyllis Magidson and me dressing a pink taffeta afternoon dress dated to about 1869, which is now the second most-viewed clip on the Museum’s Facebook page!

In addition to the physical act of mounting each garment in the collection, photographing it, and evaluating its condition, the assessment process also demands research to determine the piece’s history. Specifically, we try to verify as much as possible that an object was made or worn in New York City. In many cases, garments are accompanied by precious little information about their original wearers at the time of accession: “worn by the donor’s grandmother” or “worn by an ancestor of the donor,” perhaps.

When faced with a frock as striking as the candy pink dress, the question immediately springs to mind: “Who was she?” That is, who was the woman who wore this dress? Fortunately, we had a modicum of information with which to begin. The dress arrived at the Museum in September 1960 as part of a larger group of costume objects from Joseph Van Beuren Wittman, then residing in Phoenix, AZ, with a note that the dress was “Worn by Mrs. Henry Spingler van Beuren, who lived at 21 West 14th Street, grandmother of the donor.”

Mrs. Henry Spingler van Beuren, as we learned, was in fact Annie Teresa Clotilde Kerrigan (1838–1871), the youngest daughter of twelve children born into a devout Catholic family headed by wealthy leather merchant James Kerrigan (1789–1876) and his wife Eleanor Cecilia McLaughlin, married in 1817. James, “the most successful tanner in little old New York,”[1] had immigrated from County Donegal, Ireland, and eventually amassed an enormous fortune in an area of the Lower East Side known as “The Swamp” that enabled the family not only to support the building of several Passionist Catholic churches in New Jersey, but also to own a vast estate on the Palisades overlooking the Hudson (bequeathed by eldest daughter Sarah to the Missionary Franciscan Sisters of the Immaculate Conception in 1904 and now an area of Union City). Annie received a strong Catholic education, attending school at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Manhattanville in the early 1850s, but her social edification also encompassed a Grand Tour of Europe in 1859, where she may have picked up her flair for fashion. The family initially lived at 127 East Broadway, spending a brief period in the early 1830s on Staten Island during the great cholera epidemic, before moving in the late 1850s to 26 West 14th Street, then one of the most fashionable residential areas in the city, and just across the street from another immensely wealthy family, the Spingler Van Beurens.[2]

The area around West 14th Street—just north of what would become Union Square—was largely Spingler territory from 1788 until well into the twentieth century. Once outside the city limits, the land was part of the extensive farmland owned by the Dutch Brevoort family, comprising some 86 acres between 9th Street and 18th Street, confined by Fifth Avenue on the west and the Bowery on the east. In 1788, German immigrant merchant Henry Spingler (d. 1814) purchased twenty-two acres for about £950 from the estate of John Smith, who had acquired the land from Elias Brevoort in the 1750s. Henry’s only daughter, Eliza Mary Spingler, married James Fonerden and built the mansion at 21 West 14th Street that would become the family’s home base until its destruction in 1927. The family also owned the famous Spingler Hotel at no. 38 West 14th Street. (demolished 1938) and founded the Spingler Institute for young girls in Union Square.

Eliza’s daughter Mary Fonerden (1810–1894) and her husband Michael Murray van Buren (1800–1878)—a former mechanic who rose to become a Colonel in the Ninth Regiment of the City Guard and a superb manager of the family’s finances—lived with her mother at No. 21, and the mansion eventually acquired Michael’s family name.

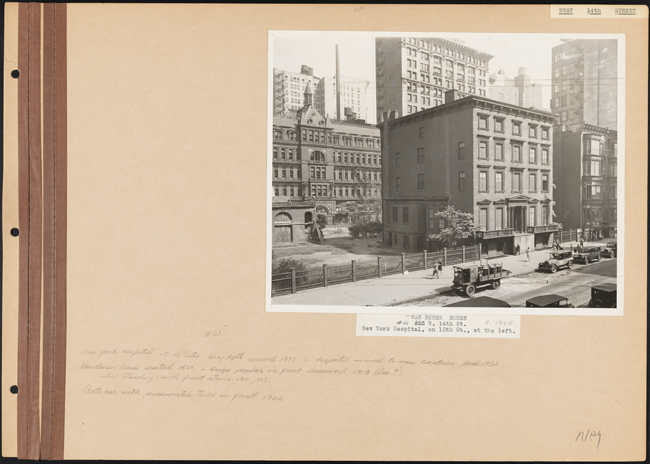

The Van Beuren (or Van Buren) mansion at number 21 West 14th Street was one of the first of the luxurious townhomes that began to ring the new park called Union Square in the 1840s. Replacing an earlier wooden house, the four-story brownstone, set on a large tract of land, housed generations of the family in splendor and became a potent symbol of the wealth and power of “Old New York” in this area of the city.

By the time the Kerrigans moved into the neighborhood, the area was beginning its transformation from residential outskirts to commercial hotbed. In 1858, R.H. Macy & Co. opened as a drygoods store at the corner of 6th Ave. and 14th Street (eventually expanding to several storefronts along 14th Street) and in 1869, Tiffany & Co. began construction on what The New York Times called “a monster iron building” at 15 Union Square West, a sign of the persistent northward march of commerce: “Slowly, but surely, the great business firms of ‘down town’ are encroaching upon the once aristocratic thoroughfares of the upper portion of the Metropolis.”[3]

At almost exactly the same time, the Kerrigan and Van Beuren families were united when Annie married next door neighbor Henry Spingler Van Beuren (1834–1906) in November 1869, and moved into her in-laws’ mansion at No. 21. She may have even purchased the eye-catching azalea pink taffeta, satin, and silk fringe dress at Macy’s before taking it to a local dressmaker to be made up into a highly fashionable afternoon ensemble. She or the dressmaker may have provided the strong sized “Book” linen that lines the train, stamped at the proper left interior hem stamped: “38 Inch / Lining Book / No. 4 20 Yns.” Largely hand sewn and comprising a one-piece trained dress, matching overskirt or “polonaise,” and sash belt with bow and streamers, the dress would have been suitable for wearing at dinner due to the low square bodice and long sleeves.

An 1896 description of the house—renowned also for a majestic poplar said to be the “largest tree that graces the streets of New-York below the Harlem River”—suggests the atmosphere in which this dress was originally seen:

“The Van Beuren mansion has during the last quarter of a century been a marvel to passers-by and provocative of lively interest. It is, in the first place, far ahead, in point of solidity of construction, of the average modern dwelling. Its interior is a charm. There is an extravagance of wide corridors and high ceilings. The equipment of furniture, tapestries, and bric-à-brac dates from the days when Chippendale was rare but not priceless. The decorations are superb.”[4]

The wide corridors would have been necessary for Annie to navigate the house in a dress such as this, supported by a whalebone or steel crinoline and several petticoats. Integral boning in the bodice provided additional reinforcement to a separate corset, supporting Annie’s 35-inch bust and 22-inch waist.

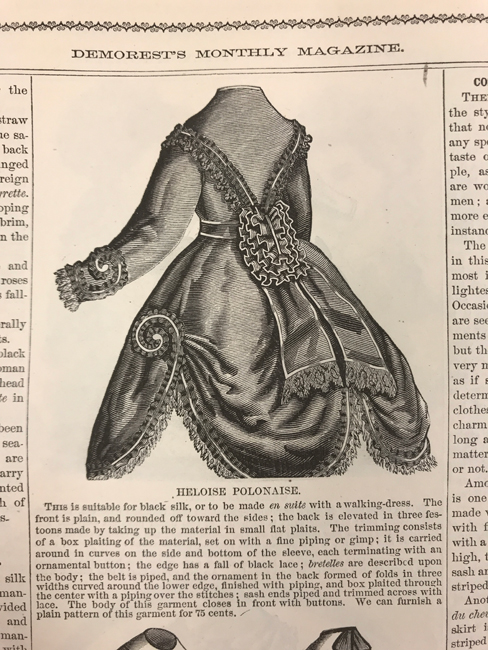

Annie likely wore this dress, in a shade probably then called “rose,” just before or just after her marriage in 1869, as it conforms to the height of fashion in this year. The “polonaise” referenced in the video—a more general 1870s term for an apron overskirt, drawn up at the hips and puffed at the rear in reference to eighteenth-century modes—was also called a “panier” overskirt, as depicted below in Demorest’s Monthly Magazine from the Museum’s collection. The dress could also date to the early months of 1870, though by later in that year the fullness at the rear of the skirt had collapsed and became much more streamlined; in addition, Annie would have been late into her first and only pregnancy.

Annie and Henry’s union was sadly short lived. Almost exactly nine months after marrying, Annie gave birth to daughter Eleanor Cecelia on August 15, 1870, the couple’s only child. Annie died on July 28, 1871, and Henry never remarried, much later becoming involved in a somewhat disastrous dam-building scheme in Arizona, where his grandson, the dress's donor, ended up. Annie is buried in the Kerrigan family vaults in Woodside, Queens. Subsequently, Henry’s sisters Mary Louise (1832–1902, who married John W. Davis) and Elizabeth (1831–1908) occupied No. 21, each maintaining it as a curious relic of a time in New York’s history when 14th Street marked the city’s northern frontier.

When Henry’s mother Mary died in 1894, The New York Times noted that the house “has long been a source of curiosity to those not acquainted with its history and the Van Beuren family. Standing back from the street, and surrounded by ample grounds, it has the appearance of a country mansion out of place.”[5] A photograph from the J. Clarence Davies Scrapbooks of street views at the Museum shows the mansion and the telltale vacant lot next door, the final vestige of the vast farmland that once surrounded it.

At Mary Louise’s death in 1902, the Times wrote, “everything is just as it was when her mother and grandmother were alive. It is filled with quaint and beautiful furniture, and the plans of the gardens, the dovecotes, and the shrubbery have not been changed in the least.”[6] “Its garden is still kept up,” the Times noted at Elizabeth’s death in 1908, adding, “Until a very few years ago it was maintained as a small farm, and the visitor to the city was often brought to see the very last cow which ever browsed in lower Manhattan as it cropped the little stretch of turf.”[7] Another photograph from the Museum’s collection shows the land behind the house where the cow once grazed, just a few years before its demolition.

Because of its wearer’s relatively short life, the dress offers not only a precise snapshot of fashion in a transitional period from about 1869 to 1870, but also a quite literally a vivid glimpse of a major New York City family’s prosperity and taste at this very moment. Never altered for later wear, it remains a precious relic of fashion and the city’s history.

This Gilded Age Afternoon Dress is featured in the first episode of our Getting Dressed video series, a behind-the-scenes look at the dazzling, fascinating, and surprising to be found in the Museum’s costume & textiles collection. Watch more from the series.