Beyond Suffrage: Equal or Special? Tracing the Equal Rights Amendment

Social Studies

Overview

Why have women sometimes claimed equality and sometimes argued for gender distinction in politics? Students will analyze primary sources from the 1920s and 1970s to examine arguments women made for and against the Equal Rights Amendment.

Student Goals

- Students will understand what an amendment is

- Students will consider the main reasons people supported and opposed the ERA at different historical moments

- Students will assess visual and written sources for information to investigate the historical arguments for and against the ERA

Common Core Curriculum Standards

Grade 4:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.4.1

Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

Grades 6-8:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

Grades 11-12:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.6

Determine an author's point of view or purpose in a text in which the rhetoric is particularly effective, analyzing how style and content contribute to the power, persuasiveness or beauty of the text.

Key Terms/Vocabulary

Amendment, Equal Rights, Ratify, Endorse, Oppose, Protective Labor Legislation

Key Figures

Shirley Chisholm, Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, Phyllis Schlafly

Organizations

Women’s City Club, International Ladies Garment Workers Union, Women’s Trade Union League, National Woman’s Party, National Organization for Women

Timeline

1908: In Muller v. Oregon, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of gender-based labor laws, which in this case allowed Oregon to limit women’s working hours.

1917: women gain the right to vote in New York

1923: Former suffragists Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman write the Equal Rights Amendment, which is introduced in Congress. Some labor activists, like Rose Schneiderman, Francis Perkins, and Florence Kelly, oppose the law and feel it will endanger labor laws that protect women and children.

1954: The League of Women Voters, formerly opposed to the ERA, endorses it.

1969: Shirley Chisholm, newly elected to the House of Representatives from Brooklyn, gives a speech supporting the ERA.

1972-1977: The ERA is reintroduced to Congress in 1972. It is ratified in 35 states, including New York.

1973-1982: conservative opposition to the ERA, led by Phyllis Schlafly, grows In 1982 the extended deadline to pass the ERA expires and the amendment falls 3 states short of passage.

1997: Rep. Carolyn Maloney of New York begins introducing the ERA for debate in every congressional session.

2017: There is a renewed push to pass the ERA; Nevada ratifies it, making the amendment just two states short of the 35 states needed for ratification.

Introducing Resources 1 – 5

After winning the vote in 1917, New York women were eager to enter electoral politics. But what to do with the vote now that they had it? Their initial hopes were high: women voters would clean up politics and improve the lives of society’s most vulnerable, especially those least able to defend themselves--its women and children. Progressive women voters did win some immediate gains, notably the successful passage in 1921 of the federal Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act, the nation’s first major social welfare program. But its supporters learned hard political lessons. By 1929 funding had lapsed, setting the stage for more political battles over women’s bodies and health in the decades to come.

The question of future strategies proved divisive, as former suffragists split over the longstanding question of whether women’s equality or women’s distinctiveness was the key to protecting them from exploitative working conditions and inequality before the law. Some New Yorkers backed a push for an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the U.S. Constitution that was launched by the National Woman’s Party in 1923. But most of the city’s leading female labor leaders and organizations opposed the ERA, arguing that it would eliminate the special protections (such as minimum wage laws for women, age of consent, mother’s pensions, and others) for working women they had already worked so hard to win. Throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s, the ERA was repeatedly introduced in Congress but failed to come to vote due to disagreement about the wording of the law and debate about how it would impact protectionist laws for working women.

In the late 1960s, a new generation of feminists began a renewed call to pass the ERA. The National Organization for Women (NOW), with New Yorkers Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, and Shirley Chisholm, among its leadership, played a prominent role in this fight. In 1972, Congress approved the Amendment, first introduced in 1923, and when it returned to the states for ratification, New York State quickly approved it.

Anti-ERA campaigns also gained traction during the 1970s. Abortion in particular—more politicized than ever in the wake of Roe v. Wade—created division, with those opposed to the ERA arguing that it would force the federal government to fund abortions. Momentum for the federal ERA slowed as the decade progressed, and New York voters failed to pass their own statewide ERA in 1975.When the (extended) deadline for passage arrived in 1982, the measure was still three states short of ratification. The failure of the ERA after decades of struggle convinced many progressive women that, despite gains in elected office and the public sphere, the fight for rights and equality was more needed than ever.

Resource 1

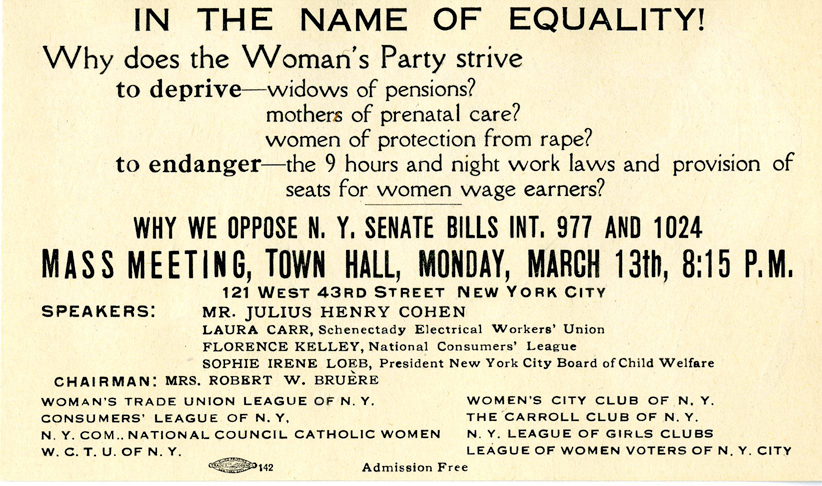

Women’s City Club Call for Mass Meeting, Lent by Hunter College,1920s-1930s

In this postcard, prominent New York women’s labor and club organizations urged women voters to oppose the ERA in New York State. Activists at the forefront of this fight argued that the ERA would eliminate their hard-won improvements in women’s workplace conditions.

Document-Based Questions

- What do the event’s organizers think about the Equal Rights Amendment?

- What effect do they think the Equal Rights Amendment will have on working women in specific?

- What are some of the words this flyer uses to express a point of view about this issue?

Resource 2

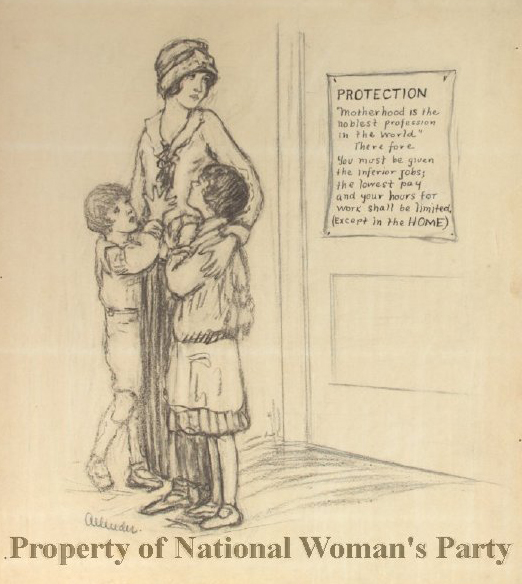

“Protective Labor Legislation for Women: How it Works” by Nina Allender. Appeared on the cover of Equal Rights on December 15, 1923. Courtesy of the National Women’s Party at the Belmont-Paul Women's Equality National Monument, Washington, D.C

This cartoon by New York-based illustrator Nina Allender, cartoonist for the National Women’s Party’s The Suffragist, opposed protective labor legislation for women, labeling it discriminatory and demanding that male and female workers alike have the same workplace protections. ERA advocates argued that protective labor legislation gave employers excuses to eliminate women in their workforces and hire only men. Most members of the National Women’s Party, for example, were middle and upper-class white women who advocated for the equality in the public sphere because protective labor legislation did not directly apply to them.

Document-Based Questions

- In your own words – What is the message of the poster she is looking at? What is it saying about rights for women? Why does the poster say “protection” at the top?

- Describe the woman’s expression in the picture. What might she be thinking as she reads this poster?

- What does the author of this cartoon seem to think about the Equal Rights Amendment? How do you think they would feel about the first source that opposed the ERA created by the Women’s City Club?

Resources 3 & 4

Shirley Chisholm with the National Women’s Political Caucus, Charles Gorry, July 12, 1971, AP Images

Shirley Chisholm Speech excerpt, 1970

This is what it comes down to: artificial distinctions between persons must be wiped out of the law. Legal discrimination between the sexes is, in almost every instance, founded on outmoded views of society and the pre-scientific beliefs about psychology and physiology. It is time to sweep away these relics of the past and set further generations free of them.

— Shirley Chisholm, “For the Equal Rights Amendment.” August 10, 1970. Speech delivered before the House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.

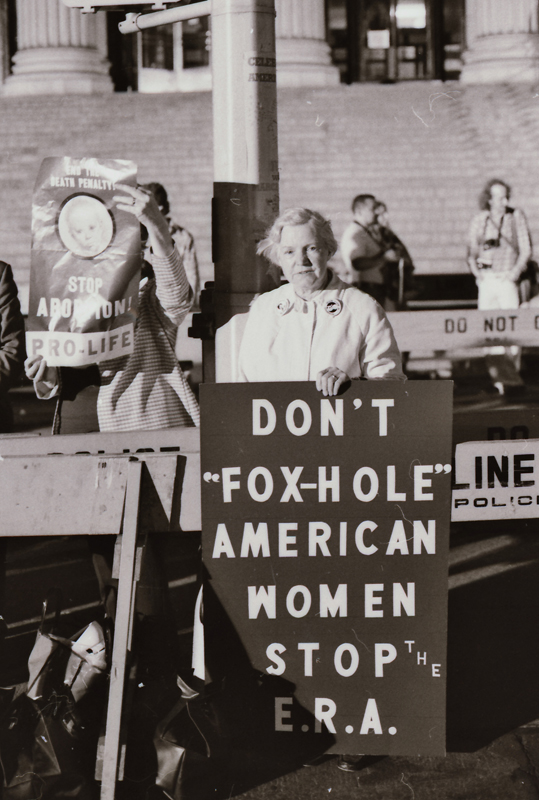

Protester at Democratic National Convention, Jo Freeman, 1976, Courtesy of the photographer

Phyllis Schlafly essay excerpt, 1972

Passage of the Equal Rights Amendment would open up a Pandora’s Box of trouble for women. It would deprive the American woman of many of the fundamental privileges we now enjoy, and especially the greatest rights of all: 1) NOT to take a job, 2) to keep her baby, and 3) to be supported by her husband.

— Phyllis Schlafly, “What’s Wrong With ‘Equal Rights’ for Women?” The Phyllis Schlafly Report, February 1972.

Document-Based Questions

- Why does Shirley Chisholm think the ERA will benefit women? Why does Phyllis Schlafly think it will have negative consequences?

- What do each of these women think is the law’s job when it comes to supporting women? (or, What role do each of these women think the law should play when it comes to supporting women?)

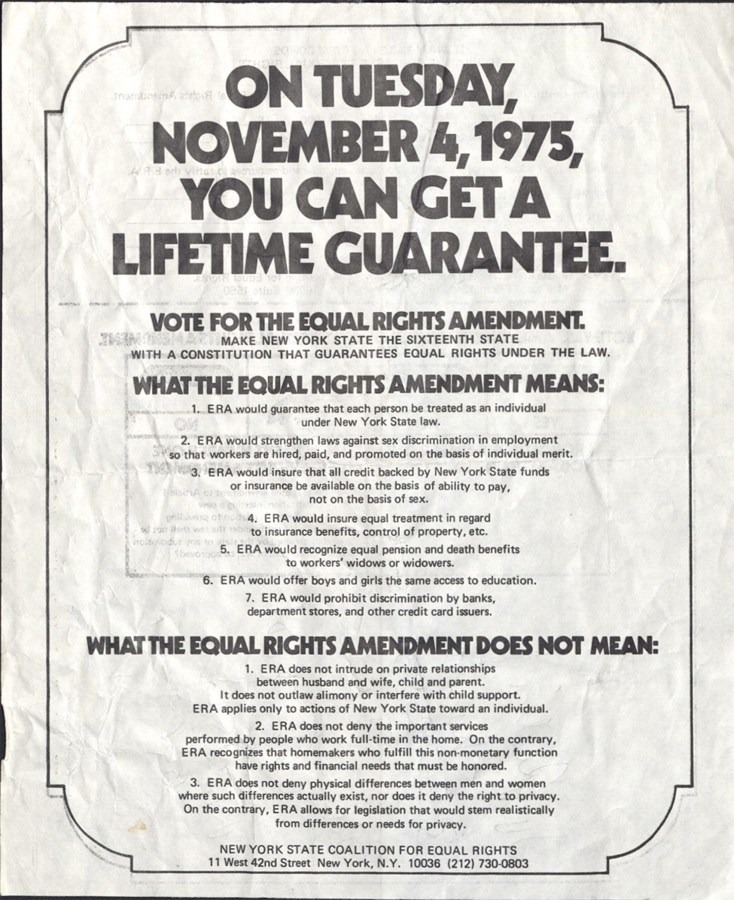

Resource 5

Document-Based Questions

- What is this flyer asking its readers to do?

- What does it believe will happen if the ERA passes?

- What fears or concerns about the ERA is it hoping to dispel (eliminate)?

- How does this poster respond to some of the arguments in Phyllis Schlafly’s speech, or support some of Shirley Chisholm’s arguments for the ERA?

Activity: Contemporary Connections

Since 2011, there has been a renewed attempt to pass the ERA. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has said it is the amendment she would most like to see added to the Constitution. In March 2017, Nevada ratified the amendment, raising the possibility that it could become law. As of now, the amendment states:

Section 1. Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Section 3. This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification

Imagine that you work for a member of Congress--you have been asked to brief them on this issue before they vote on it.

- What information would be important for them to know?

- What possible impacts could passage of the ERA have?

- How do you think they should vote?

Sources

Chisholm, Shirley. “For the Equal Rights Amendment.” August 10, 1970. Speech delivered before the House of Representatives, Washington, D.C. Voices of Democracy Website: http://voicesofdemocracy.umd.edu/chisholm-for-the-equal-rights-amendment-speech-text/

Schlafly, Phyllis. “What’s Wrong With ‘Equal Rights’ for Women?” The Phyllis Schlafly Report,February 1972. Eagleforum Website: http://eagleforum.org/publications/psr/feb1972.html

Additional Reading

"The Equal Rights Amendment: Unfinished Business for the Constitution.” http://www.equalrightsamendment.org/congress.htm

Freeman, Jo. We Will Be Heard: Women’s Struggles for Political Power in the United States. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008.

May, Vanessa H. Unprotected Labor: Household Workers, Politics, and Middle-Class Reform in New York, 1870-1940. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Spruill, Marjorie J. Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics. New York: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Field Trips

This content is inspired by the exhibition Beyond Suffrage: A Century of New York Women in Politics. If possible, consider bringing your students on a field trip by July 2018! Find out more.

Acknowledgements

Education programs in conjunction with Beyond Suffrage: A Century of New York Women in Politics are made possible by The Puffin Foundation Ltd.