Beyond Suffrage: “Working Together, Working Apart” How Identity Shaped Suffragists’ Politics

Social Studies

Overview

By analyzing texts and images, students will understand how experience, identity, and political priorities led New York suffragists to seek the right to vote and shaped the strategies they used to achieve their political aims.

Student Goals

- Students will be able to identity key figures and organizations within the suffrage movement and explain their distinctions.

- Students will understand how and why class- and race-based differences between individual suffragists often divided the movement.

- Students will learn how suffragists’ race, gender, and class experiences shaped their political views and the strategies they used to promote the cause of women’s suffrage.

Common Core State Standards

Grade 4:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.4.1

Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

Grades 6-8:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.

Grades 9-10:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.9-10.1

Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

Key Terms/Vocabulary

Suffrage, Vote, Ballot, Franchise, Amendment, Nineteenth Amendment, Division, Class, Prejudice, Race, Suffrage, Supremacy, Coalition, Demonstration, Tactic

Key Figures

Harriot Stanton Blatch, Rose Schneiderman, Alva Belmont, Sarah J.S. Tompkins Garnet, Gertrude Bustill Mossell, Carrie Chapman Catt, Mabel Lee

Organizations

National American Woman Suffrage Association, Equal Suffrage League, Equality League of Self-Supporting Women, Women’s Trade Union League, Woman Suffrage Party

Introducing Resource 1

In the early 20th Century, New York City’s suffrage activists were a diverse group, made up of women drawn from across the city’s ethnic, racial, and class divisions. Carrie Chapman Catt, a staunch non-partisan and New York’s premier suffrage organizer, led the one million members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Wealthy New York women such as Alva Belmont funded suffrage campaigns, while Harriot Stanton Blatch, the daughter of feminist pioneer Elizabeth Cady Stanton, galvanized working-class immigrant women, including Rose Schneiderman and other labor organizers, to join the suffrage fight.

Although many of New York’s suffragists reached across ethnic and class lines to build political coalitions, some white suffragists often excluded or were hostile to black women. Many white suffragists, Catt among them, excluded black women from their organizations and demonstrations because they feared they would lose organizational funding and members and risk the passage of the 19th amendment, which was achieved through a state-by-state campaign. Catt famously argued that including black members would dampen Southern support for a national amendment and that black women would more easily get the vote if they stopped “asking for membership.” Most white suffragists assumed that despite their exclusion, African-American women in New York would win the vote when white women did. It is clear that Catt and other white suffragists in the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) believed that exclusion and employing racial prejudice to appeal to Southern voters was politically expedient for white women to secure suffrage, which some saw as a stepping-stone for black women to eventually achieve the vote.

Unsurprisingly in the face of such prejudice, black suffragists such as Sarah Tompkins Garnet, founder of the Equal Suffrage League in Brooklyn, established their own organizations. The Equal Suffrage League—like many black suffrage organizations—fought for racial equality as well as for the vote. Black suffragists organized to end lynching, to combat laws against interracial marriage, and to end Jim Crow legislation. They believed that securing the right of black women to vote was just one crucial step in the ongoing fight against racism and segregation.

This table includes short bios of notable suffragists and key quotations.

Read each bio and quotation with the following questions in mind: What issues was the suffragist involved in that led them to advocate for women’s suffrage? According to their quotations, what were their views on suffrage and strategy for securing the vote?

Harriot Stanton Blatch and Rose Schneiderman

Harriot Stanton Blatch and Rose Schneiderman, 1915, Courtesy of the Rose Schneiderman Collection, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University

Harriot Stanton Blatch (left), daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Rose Schneiderman, a Russian-Jewish immigrant and garment-union activist, joined together to connect working women and educated, professional suffrage leaders in New York. While the two symbolized the class and ethnic collaboration within the suffrage movement in the city, their long friendship also included clashes that reflected those of the larger movement, especially over the question of labor laws that offered special protection to women.

“What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist — the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art… The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with." — Rose Schneiderman

“If we win the Empire State…all the States will come tubling down like a pack of cards.” — Harriot Stanton Blatch, letter to Alice Paul, August 26, 1913

Alva Belmont

Alva Belmont, George Grantham Bain, 1915, Museum of the City of New York, Portrait Collection, F2012.58.87

Wealthy suffragist and philanthropist Alva Belmont used her fortune to establish the Political Equality Association in New York, which later merged with radical feminist Alice Paul’s group to become the National Woman’s Party. Like Paul, Belmont embraced militant suffrage tactics and also recruited African-American suffragists—such as Irene L. Moorman and Frances Keyser—to join her organization. Yet Belmont also provided support to the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference, which openly opposed the vote for black women.

“We are all equal -- rich and poor alike -- and all should join in this movement.” — Alva Belmont

Gertrude Bustill Mossell

Gertrude Bustill Mossell, c. 1890 , Courtesy of the University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania

One of the leading black writers of the late 19th century, Gertrude Mossell used her column “The Woman’s Department” in the New York Freeman—then the leading African-American newspaper in the country—as a platform to vocalize her support for suffrage and the right of women to own property and attend college. In 1894, Mossell published her groundbreaking feminist history The Work of the Afro-American Woman, which traced the accomplishments of black female professionals in the suffrage, temperance, and abolitionist movements. Her daughter, Mary "Mazie" Mossell Griffin, would follow in her footsteps by serving as chairperson of the suffrage committee of the Northeastern Federation of Women’s Clubs and of the legal department of the National Association of Colored Women.

“The securing of the ballot meant not only the future of the women of color in America. It also meant the correcting of many evils which if corrected would mean a new day for the American Negro.” — Mazie Mossell Griffin, daughter of Gertrude Bustill Mossell, writing in 1947

Sarah J.S. Tompkins Garnet

Sarah J.S. Tompkins Garnet, c. 1860, Courtesy of the Photographs and Print Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the New York Public Library / Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

Sarah J.S. Tompkins Garnet was a key figure in the early wave of black woman suffrage activism in New York. The Brooklyn native participated in multiple organizations advocating for gender and racial equality: she founded the Equal Suffrage League in Kings County in the late 1880s and organized for the vote through the National Association of Colored Women. She also made a successful career as a schoolteacher and became the first African-American woman principal in a New York City public school.

“At the special meeting of the Equal Suffrage League...Mrs. S. J. S. Garnet, national suffrage superintendent, presented a petition which had been arranged by the league, asking for the enactment of such legislation by Congress as will enforce the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.” — The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 30, 1908

Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt, George Grantham Bain, 1910, Museum of the City of New York, Portrait Archives, F2012.58.225

As President of the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association and the New York State Woman Suffrage Party, Carrie Chapman Catt developed the so-called “Winning Plan,” a strategy to work for passage of suffrage at the state and national levels simultaneously. Catt’s leadership was instrumental to the passage of the 1917 New York State woman suffrage referendum and the federal amendment that followed in 1920. Catt excluded black women from joining white suffrage organizations such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The national organization, which was based in New York, employed racial prejudice as a strategy to persuade Southern voters to pass the Nineteenth Amendment. However, Catt assumed that black women would obtain the vote in New York when white women did, and thought that suffrage could be expanded if white women secured the vote first. Unlike most black suffragists who saw the fight for women’s suffrage and against segregation as fundamentally linked, Catt and likeminded suffragists considered racial equality secondary to their primary political goal: securing the Nineteenth Amendment.

“The vote is the emblem of your equality, women of America, the guarentee of your liberty.” — Carrie Chapman Catt, August 26, 1920 (upon passage of the national amendment)

“Woman suffrage in the South would so vastly increase the white vote that it would guarantee white supremacy if it otherwise stood in danger of overthrow...If the South really wants White Supremacy, it will urge the enfranchisement of women.” — Carrie Chapman Catt

Mabel Lee

Mabel Lee, 1915, Courtesy of the Barnard Archives and Special Collections

A member of the Women’s Political Equality League, Mabel Lee led Chinese and Chinese-American women in a pro-suffrage parade down Fifth Avenue in 1917. As an immigrant herself, however, Lee was barred by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 from voting in the United States, even after the passage of the suffrage amendment brought the vote to American women of other races and ethnicities. Lee attended Barnard College and later became the first Chinese woman to earn a doctorate from Columbia University.

"... feminists want nothing more than the equality of opportunity for women to prove their merits and what they are best suited to do." — Mabel Lee

Document Based Questions

- Based on the bios and quotations, what does suffrage mean to each of these women? For example, what does suffrage mean to Mabel Lee or Rose Schneiderman?

- How do Alva Belmont and Rose Schneiderman talk about women from different social classes? Do they believe that poor and rich women share political beliefs? Why or why not?

- The 14th amendment grants citizenship to anyone born in the U.S. and forbids states from depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” or denying any person equal protection of the law.” Why did Sarah Tompkins Garnet ask for the enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment during a 1908 meeting of the Equal Suffrage League? Why would she connect the Fourteenth Amendment to the issue of suffrage?

- Why might the National American Woman Suffrage Association be unwilling to take a stance on the “race question” when it came to suffrage? Notice that Carrie Chapman Catt mentions leaving it up to each state to determine “other qualifications" for potential voters in order to persuade southern states who wished to restrict black suffrage.

- How did black suffragists like Garnet and Mossell understand the relationship between suffrage and racial equality?

- Why would a woman like Mabel Lee, who would be prohibited from voting because of her race even after the passage of the national suffrage amendment, still campaign for women’s right to vote?

Introducing Resource 2

New York City activists provided much of the funding and leadership for the suffragist cause at the local, state, and national levels. They introduced strategies of mass organizing and publicity, and were well-aware that by staging their marches and parades in New York City, the country’s media capital, they could attract a national audience for their cause. But not all suffragists were invited to participate equally in public actions; some suffragist marches were segregated, and black suffragists often had to fight for the right to demonstrate publically alongside white activists.

One notable incident of a segregated suffragist march was the Women’s Suffrage March of 1913, which occurred in Washington, DC one day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. The march organizers, worried that southern women would not march in an integrated parade, decided that black women would march at the back of the procession. Many black women refused to comply with this plan and instead marched alongside white women under the banner of their state. Famed Chicago journalist Ida B. Wells was one of the black suffragists who dared to march next to her fellow white protesters. Wells is best known as an anti-lynching advocate, but she was also a dedicated suffragist who co-founded the Alpha Suffrage Club with white suffragist Belle Squire. Well’s actions at the march captured the attention of the national media—a photograph of her at the head of the Illinois delegation ran on the front page of the Chicago Tribune—and brought increased attention to black suffragists’ demands for racial equality within the movement.

This photograph is titled “Youngest Parader in New York City History”—a reference to the presence of a toddler at a 1912 suffrage parade—but the image also captures an exchange between a white suffragist and a black suffragist marching alongside her.

Youngest Parader in New York City History, American Press Association (1912). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-5585.

Document Based Questions

- Describe what is happening in the photograph. What do you notice about the suffragists who are participating in the march?

- What are some of the kinds of diversity we see represented in this image? What kinds are we missing?

- What might the women in the foreground of this image be feeling based upon their expressions? What do you notice about the facial expressions of the suffragists? What do you imagine was happening in this scene?

- In the context of the march organizers asking black suffragists to march in the back of the procession in fear of losing support from southern women, why would Ida B. Wells or the black suffragist featured in this photograph insist on integrating suffragists marches?

- What are some of the tactics suffragists are using to communicate their political message in this image?

- What do you think the photographer of this image was trying to communicate about the suffrage movement?

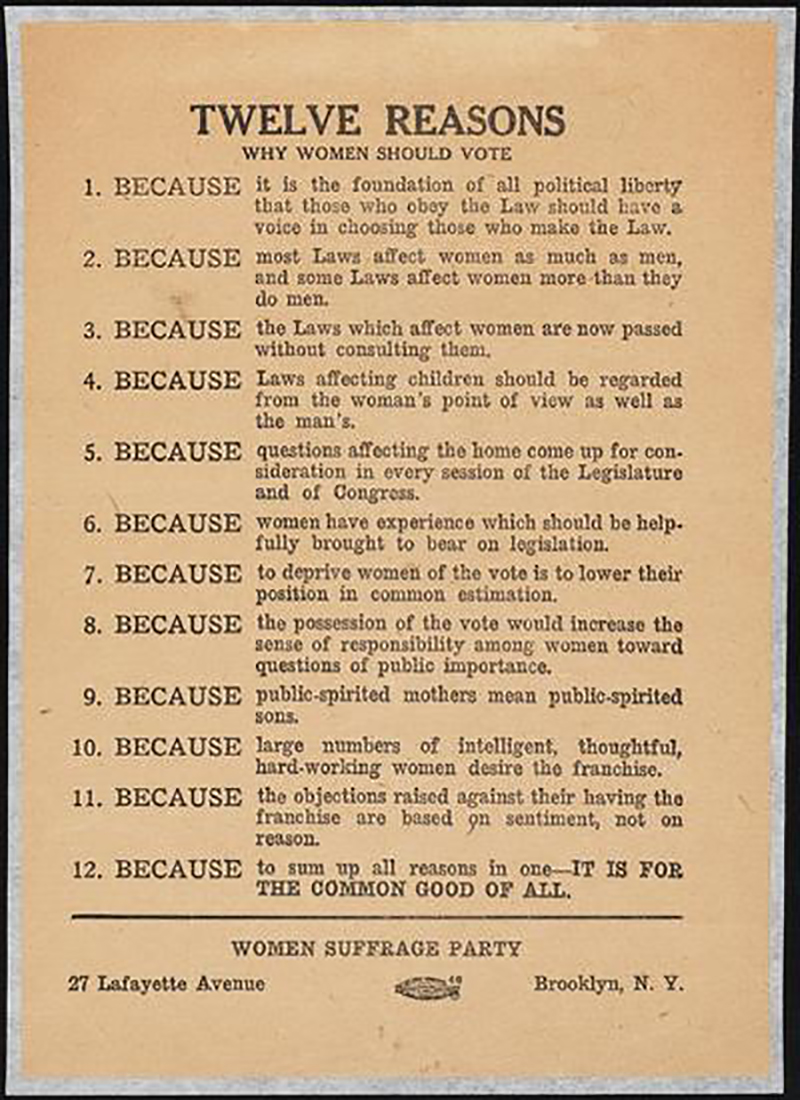

Introducing Resource 3

This flyer was circulated by the Woman Suffrage Party, a suffragist organization founded by Carrie Chapman Catt. The Woman Suffrage Party was non-partisan and its members devoted much of their energy to promoting equal pay for women in the workforce, passing out suffrage literature, and organizing parades, marches, and demonstrations.

“Twelve Reasons Why Women Should Vote,” 1915. Museum of the City of New York, Manuscripts and Ephemera Collection, F2011.16.2

Document Based Questions

- What is the basic argument of this flyer?

- Why does the flyer begin with reason #1?

- In reason #6, what kinds of “experience” do you believe the suffragists are referring to when they argue that women’s experiences “should be helpfully brought to bear on legislation”?

- What groups of women do you believe this flyer is meant to appeal to? Why?

- What do you believe suffragists meant in reason #7 when they state that “to deprive women of the vote is to lower their position in common estimation”?

- How might women from very different backgrounds like Mabel Lee or Rose Schneiderman or Alva Belmont have responded to this flyer, and its statement that women suffrage is “for the common good of all”? Which reasons might have appealed to each of them most strongly? What reasons might each of them add to the flyer?

Introducing Resource 4

The excerpt below is from “Dirt, Smell, and Sweat,” written by Margaret H. Sanger and published in The New York Call, December 24, 1911, p. 15. The New York Call was a newspaper published between 1908 and 1923, and affiliated with the Socialist Party of America, which supported women’s suffrage. Nurse and reformer Margaret Sanger is best known for leading the movement to legalize contraception for women in New York, but she was also a proponent of suffrage.

“To the Editor, Woman's Sphere:

At a meeting of the Woman's Suffrage party of the 27th Assembly District a few days ago a tall, beautiful and charming woman named Mrs. Weeks, acted as chairman of the meeting. In what was called her maiden speech, she mentioned among other things that the men who objected to woman's voting because she would be obliged to bump against the dirty, smelly and sweaty men at the polls, evidently did not object to her bumping against them at other times; they objected only on Election Day and at the ballot box. Then she offered the following suggestion as a cure for this objection. "to remove the dirty, smelling, sweaty men from the polls," so that she and her class could vote undisturbed.

But what about the women who are liable to be just as dirty, smelly and sweaty as their working brothers? Are they, too, to be removed? Dirt is dirt, smell is smell, and sweat is sweat, no matter on whom these unfortunate afflictions happen to be. And if the chairman and her class object to the smell of the workingman, so will they object to the smell of the working woman.

Throughout the meeting the atmosphere was laden with class arguments. Such nice and polite and kind arguments in favor of the women in the home, who need the ballot to get CLEAN milk, clean streets and fresh air. Not one word about the millions of women driven out of the home into the factories and shops. Never a word about the women who cannot give any kind of milk to their children, but give them black tea and coffee and sell the milk and cream to her own class. These women and these conditions have not been considered by the Woman's Suffrage party, and it is doubtful if they will consider them until the working woman stands shoulder to shoulder with her working brother for the emancipation of her class.

The only thing which seems to concern this chairman and her followers is POLITICAL FREEDOM. No other kind of freedom enters into their arguments... The idea of making woman's sphere ‘unlimited, unbounded,’ as the Socialist women are striving for, has so far scarcely entered their craniums [skulls/heads]…”

Document Based Questions

- Who do you imagine Margaret Sanger is addressing in this letter?

- According to Margaret Sanger, what are the concerns of the Women’s Suffrage Party? In her mind, what key issues are they overlooking?

- In this letter, Sanger argues that “political freedom” is the only kind of freedom of importance to the Woman’s Suffrage Party. What other kinds of freedom do you think she feels is important? Why?

- What is Margaret Sanger referring to when she writes of the “woman’s sphere” in the last sentence?

Activity

In this lesson, students have been introduced to a few of the diverse group of women who participated in the suffrage movement. They learned how lived experience shaped the goals and strategies of individual suffragists. Black women like Sarah Tompkins Garnet saw suffrage as one of the many rights they needed to secure in order to obtain racial justice and equality. For activists like suffragist and labor organizer Rose Schneiderman, the right to vote was a necessary step to address unjust working conditions and economic inequality. Students also learned how race and class-based differences often divided individual suffrage organizations with the larger movement. They analyzed Carrie Chapman Catt’s decision to adopt exclusion rather than inclusion of black women to expedite the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, and explored how black suffragists choose whether to work with or apart from white suffragists as they fought for racial and gender equality.

In the following activity, students will put themselves in the shoes of Sarah Tompkins Garnet and her fellow Equal Suffrage League activists who are planning a suffrage action. As they strategize, students will gain a deeper appreciation of not only how suffragists appealed to those who disagreed with their objectives, but also how they understood the relationship between suffrage and other issues of gender, class, and racial equality.

As members of the Equal Suffrage League, students will plan a demonstration in support of New York’s passage of the suffrage amendment. As they strategize, ask students to consider:

- What audience they are addressing? The Equal Suffrage League is an organization founded and run by African-American women who are seeking the vote. Should the League speak primarily to black women, or should they address men and women of across racial groups?

- Who will be asked to join the demonstration?

- What kind of action will they engage in? A march, a protest, a public speech?

- What language will they use? Will they speak specifically to the concerns of a single group or to women collectively?

- Where will the action be staged?

- How will the members of the League and their allies present themselves? What clothing will they wear? What kinds of materials will they carry?

- Will they ask for the vote only or for other rights that matter to the League’s members?

Sources

Citations for the quotations in the “Meet the Suffragists” section (Resource 1):

- Rose Schneiderman, “Bread and Roses” Strike Speech, Lawrence, Massachusetts, August 1912.

- Harriot Stanton Blatch, letter to Alice Paul, August 26, 1913 (NWP-SY records, reel 4)

- M. Mossell Griffin, “Early History of Afro-American Women,” National Notes, March-April 1947, 7.

- “Afro American Notes.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 30, 1908, 5.

- Carrie Chapman Catt, August 26, 1920 (upon passage of the national amendment)

- Carrie Chapman Catt, “Letters from the People: Woman Suffrage and the South.” The Times-Democrat, Thursday, March 19, 1903, 11.

- Mabel Lee, Chinese Student Monthly, 1914.

“Youngest parader in New York City History,” American Press Association (1912). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Women Suffrage Party, Twelve Reasons Why Women Should Vote, ca. 1915. Museum of the City of New York

Margaret Sanger, "Dirt, Smell and Sweat," New York Call, Dec. 24, 1911, p. 15.

Additional Reading

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Woman Suffrage and Women’s Rights. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Goodier, Susan and Karen Pastorello. Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017.

Gordon, Ann Dexter and Bettye Collier-Thomas, editors. African American Women and the Vote, 1837-1965. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1997.

Kraditor, Aileen S. The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement: 1890-1920. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1981.

Neuman, Johanna. Gilded Suffragists: The New York Socialites who Fought for Women's Right to Vote. New York: New York University Press, 2017.

Newman, Louise Michele. White Women's Rights: The Racial Origins of Feminism in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.

Contemporary Connections

“Women and Their March on Washington,” a series of op-eds that outline a variety of opinions on the effectiveness and importance of women’s protests in the months following the November 2016 presidential election. Of particular interest is Aishah Shahidah Simmons’ contribution.

https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2017/01/09/women-and-their-march-on-washington/my-feelings-about-the-womens-march-have-evolved

The mission statement and principles of the “Women’s March,” the women-led movement that organized the January 2017 marches across the country.

https://www.womensmarch.com/mission/

Field Trips

This content is inspired by the exhibition Beyond Suffrage: A Century of New York Women in Politics. If possible, consider bringing your students on a field trip by July 2018! Find out more.

Acknowledgements

Education programs in conjunction with Beyond Suffrage: A Century of New York Women in Politics are made possible by The Puffin Foundation Ltd.