Louis Bouché, The Stettheimer Dollhouse and Mama’s Boy

Tuesday, September 6, 2016 by

Editor’s Note: Peer inside the Stettheimer Dollhouse on the Museum of the City of New York’s second floor, and you’ll find a host of tiny works of art decorating the walls and halls of the opulent, doll-sized rooms. Lean in closer and you’ll see that many of these original, miniaturized works have the stamp of renowned avant-garde artists of the 1920s, including Marcel Duchamp, Alexander Archipenko, Marguerite Zorach, Gaston Lachaise, and Louis Bouché. Some, like a 2 x 3-inch rendition of Nude Descending a Staircase contributed by Marcel Duchamp are instantly recognizable. But curators are still tracing down the inspiration for others. Recently, Curator of Paintings and Sculpture Bruce Weber discovered the source for one of the works from the dollhouse gallery in a life-size gallery upstate.

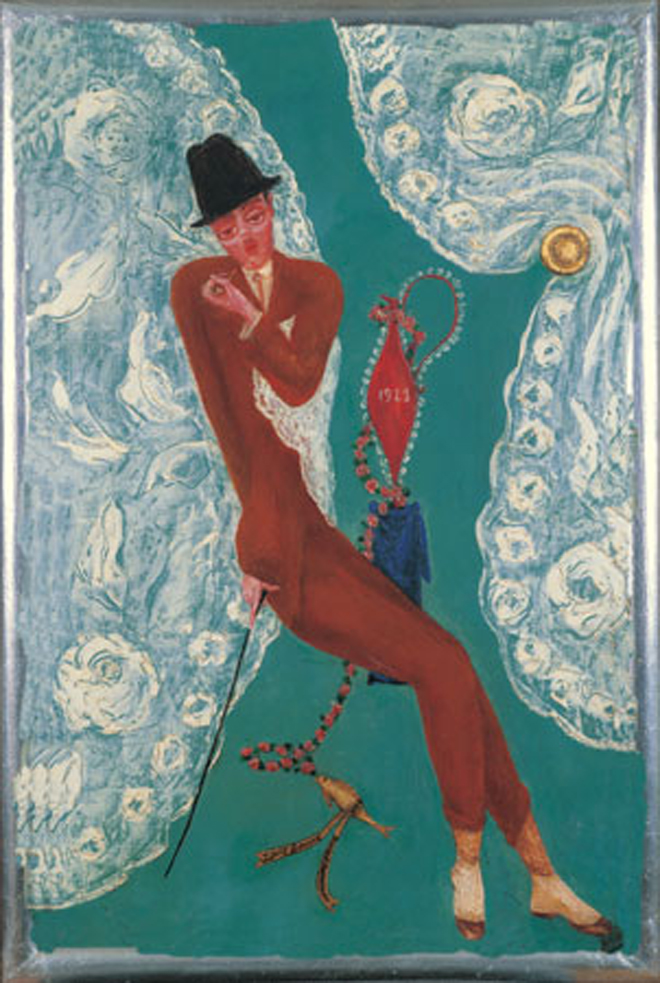

This spring I discovered Louis Bouché’s oil painting Mama’s Boy in an exhibition at the Woodstock Artists Association and Museum in Woodstock, New York, and recognized this recent addition to their collection as the source for the artist’s miniature version in the famous art gallery of Carrie Stettheimer’s dollhouse in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York. The experience inspired me to look into the background of the painting and Bouche’s relationship with the Stettheimer sisters. This long narrow canvas of a child gazing from between layers of lace curtains is one of the artist’s so-called Nottingham lace curtain paintings. Nottingham lace is a form of machine woven bobbin lace that was developed in England during the course of the 1840s. In his unpublished autobiography, Bouché explained that the lace curtains that he pictured in this series were an attempt to glorify bad Victorian taste.

Campy and smart-alecky works such as Mama’s Boy led Bouché to be referred to as the “bad boy of American art” by the writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten, who, along with Bouché, was an attendee of the Stettheimer’s famous New York salon. Bouché himself was something of a “mama’s boy.” His mother Marie brought him up alone following her husband’s death in 1908. He related in his unpublished autobiography that following this event his mother “centered all of her love on me. Whenever I took a liking to, or got a ‘crush’ on a girl, mother hated her and went to fantastic lengths about it. When she was particularly jealous, I would have to appease her by buying flowers. As soon however, as the ‘crush’ was over, my mother would take up the girl, become friends with her, invite her to the house and praise her to me.”

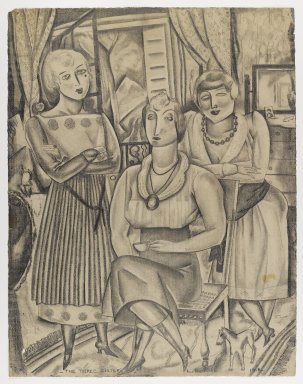

Bouché began to associate with the Stettheimer sisters in about 1918, the date he produced his graphite drawing of the siblings in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art. In this work Carrie is regally seated at center wearing a large cameo necklace and daintily holding a teacup. To her left, her painter sister Florine confidently stands with arms folded, and at right, her author sister Ettie leans forward engagingly with her arms crossed atop the back of Carrie’s chair. In the background is a pair of what appear to be Nottingham lace curtains. Like Bouché, the sisters were the children of a formidable matriarch. Rosetta Walter Stettheimer raised her children alone following her husband’s desertion of the family in Europe sometime before 1901. Remaining unmarried, the sisters lived at home where they shared an elegant style of life and the friendships of leading American and European artists and writers. In the course of the 1920s, Rosetta’s health deteriorated, and she required an increasing amount of attention from her daughters, who divided their time so that at least one of them was always at home with her.

Carrie’s work on the dollhouse stretched out for nearly 20 years due to family responsibilities, including caring for her mother and assorted household duties, as well as other social and personal interests. In pursuit of time to work on the dollhouse undisturbed, Carrie would rent an apartment at the Dorset Hotel, a block from the Stettheimer’s triplex apartment at Alwyn Court. Immediately after her mother’s death in 1935 she moved full time into the Dorset and, ironically, abandoned working on the dollhouse, which remained in storage for 10 years until it was donated to the Museum of the City of New York by Ettie a year after Carrie’s death in 1944.

Besides a demanding mother, Louis Bouché and Carrie shared a penchant for outlandish attire, an offbeat sense of humor, and a broad knowledge of the visual arts. Florine’s 1923 portrait of Bouché in the collection of the Heckscher Museum of Art captures the artist’s sense of flair and his flamboyant personality. She exaggerates his height and attire while surrounding him at either side with – what else! – a pair of artfully-spaced lace curtains. Florine’s involvement with Bouché blossomed in the early 1920s when he was the manager of the Belmaison Gallery at the Wanamaker Department store in Lower Manhattan and included her paintings in a number of exhibitions. Under the artist’s direction, the gallery became well known for showing the work of the modern French school (including Picasso, Léger, and Matisse), and a diverse group of contemporary American artists.

Carrie is best known today for the museum’s dollhouse, and putting together wild party menus. She designed elegant and elaborate meals for her family’s soirées, which featured such imaginative dishes as feather soup, smelts stuffed with mushrooms, lobster in aspic and Brabanter torte. Stately in appearance, she was said to have resembled Queen Mary and wore tiaras as well as jeweled dog collars. Is it any surprise that Carrie wanted Bouché’s daffy and audacious Mama’s Boy to grace the gallery of her dollhouse, created at moments of freedom during getaways to the Dorset Hotel?

Images of works in the collections of the Woodstock Artists Association

and Museum, Brooklyn Museum, and Heckscher Museum used with permission from each institution.