From Expressway to Contemplative Oasis: The Elevated West Side Highway

Thursday, November 12, 2015 by

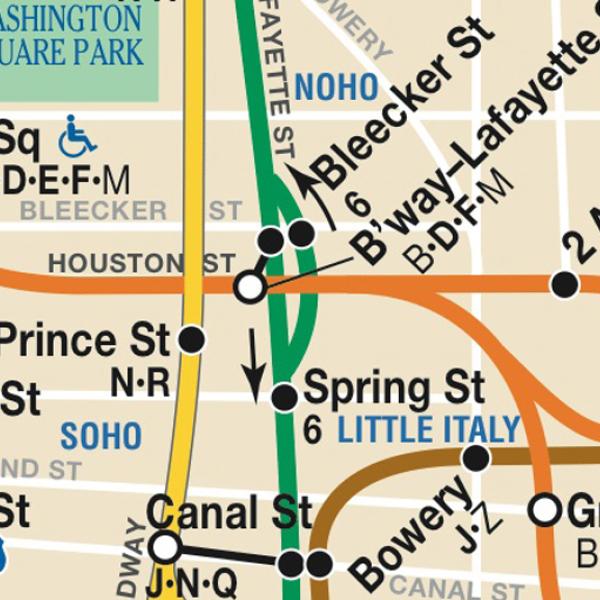

When racing in a cab down West Street trying to make it in time for a meeting, how many people think back just a few decades when an elevated expressway ran down the western edge of the city from the Henry Hudson Expressway to Battery Park? Of course, I am speaking of the old Elevated West Side Highway, a Robert Moses project initiated just as car culture was coming into its own. The first section of the highway opened to the public in 1930, but the entire project was not realized until 1951. A precursor to the expressway era that would follow, the West Side Highway was praised early on by The New York Times as it would “afford immediate and measurable relief to traffic congestion on Riverside Drive” and allow motorists to drive all the way from downtown “nearly to Poughkeepsie without having to stop for a traffic light or slow up for an intersection.”

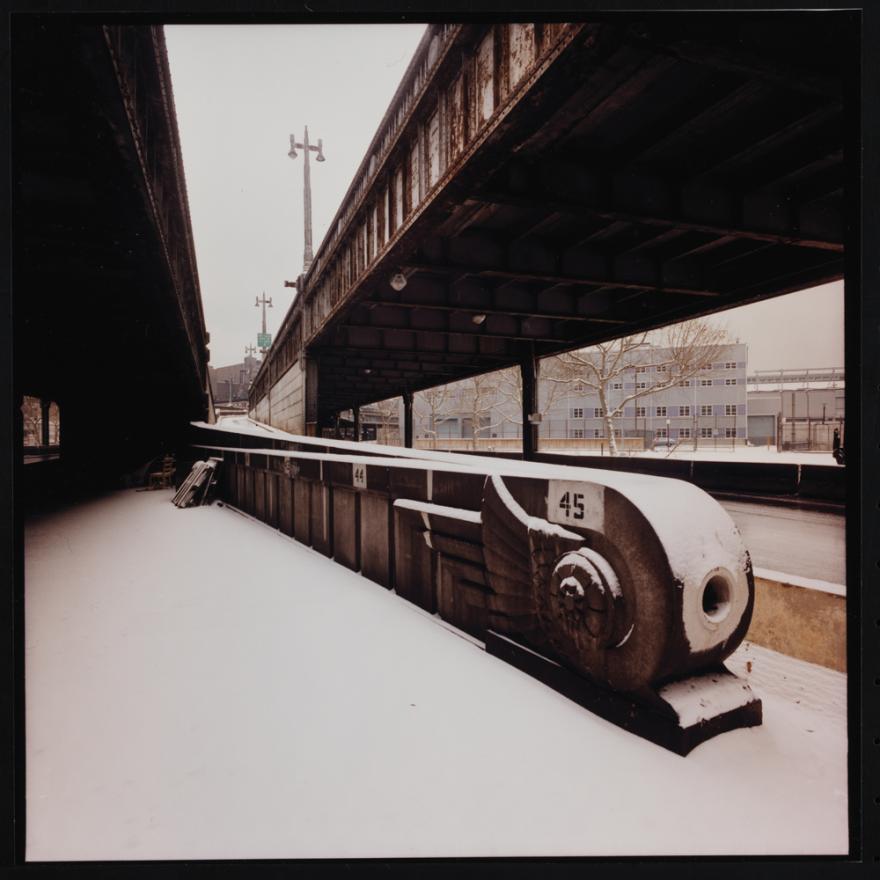

The highway was constructed with beautiful Art Deco ornamentation, reflective of its era, but soon after came the realization that it was too difficult for tractor tailors to navigate: the on-ramps were too narrow and the turns were often too tight. The roadway and its structural underpinnings were not properly maintained and on December 15, 1973 a section of the highway collapsed under the weight of a dump truck carrying asphalt.

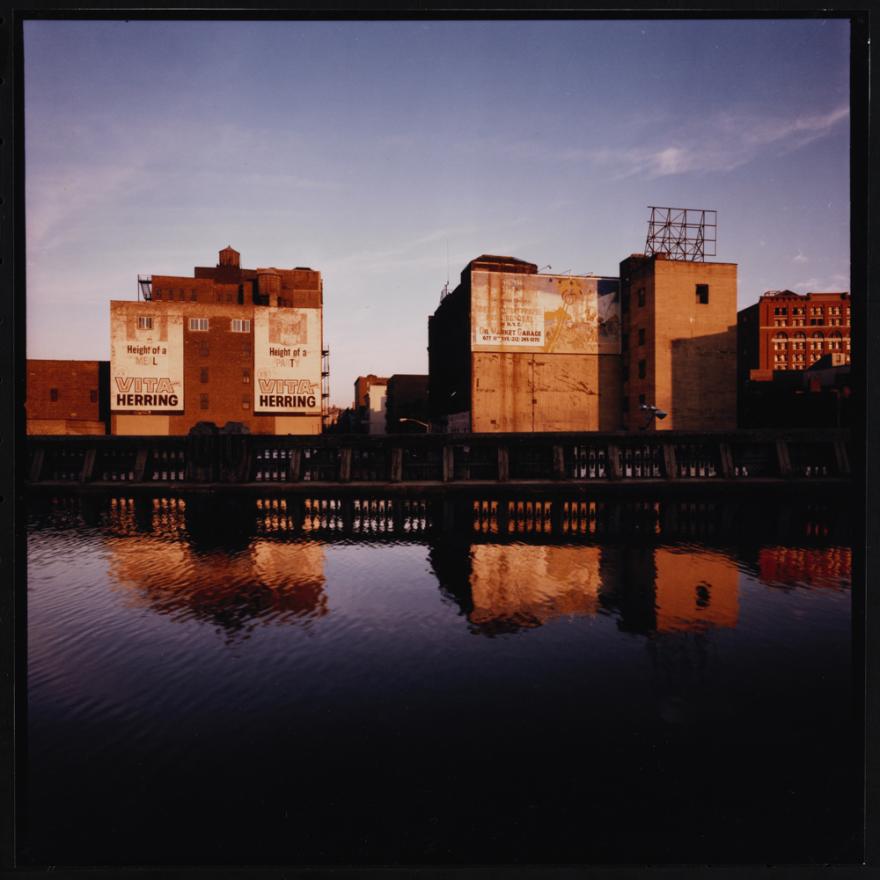

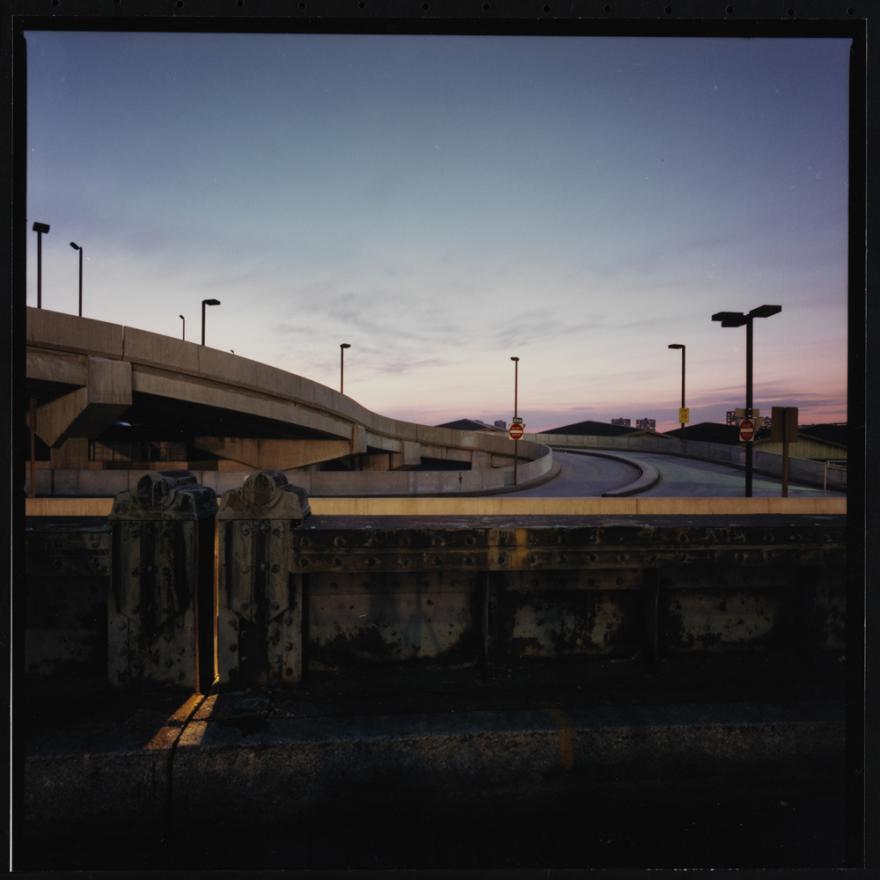

The accident initiated a civic debate about the future of the expressway, which was closed in sections and eventually demolished, a process that began in 1977 and wasn’t completed until 1989. It was in this state of devolution and abandonment that photographer Jan Staller first encountered the West Side Highway in the late 1970s. The City Museum recently acquired a collection of 34 prints by Staller from this period that were compiled as a book dummy for his eventual publication Frontier New York (Hudson Hills Press, 1988). Staller’s photographs of the area began in a casual way as he explored the city, escaping the dark loft where he lived on Walker Street. In a forthcoming documentary, A Curiosity for the World,directed by Dale Schierholdt, Staller explained, “I liked going there for the peace and quiet. The sense of horizon and afternoon light…At some point I stuffed a 35mm camera with Kodachrome film in a backpack.”

As he became more serious about make pictures of the highway he brought along a Hasselblad Superwide, color negative film and a small tripod. Staller went on to say, “I found that there was a very kind of contemplative or spiritual quality to the twilight in Manhattan…. I was going to find some kind of approximation of the natural world. So after the sun started getting low in the sky, the city started to quiet down…. The peace was very seductive.”

A sense of place is at the core of this body of work, and the effect of light is a key ingredient to its success. The mixed light of sunset in combination with the sodium vapor and incandescent lighting of the city have a remarkable effect on the finished prints. Many of the images were created using time exposures – sometimes up to five minutes long. The results are lush, saturated images of the city that belie the stark setting.

Today, the elevated roadway is gone and cars rip up and down West Street past joggers and tourists at the water’s edge. On the right evenings it is still possible to see something of the glowing twilight Staller was looking for about thirty years ago. To see the rest of his photographs in the Museum’s collection, visit the Collections portal.

![Edmund V. Gillon, [West Side Elevated Highway], ca. 1975. Museum of the City of New York, 2013.3.2.698](/sites/default/files/MN124669.jpg)

![Leland Bobbé, Subway [Voice of the Ghetto], 1974. Archival pigment print. Gift of the photographer. 2016.10.7.](https://www.mcny.org/sites/default/files/styles/mcny_col_3_thumbnail/public/mn185974_0.jpg?itok=8q3-MZ35)