City of Workers, City of Struggle Lesson: Civil Rights and Union Rights

Racial Justice and Labor Politics in 1960s New York City

Social Studies

Overview

Through analyzing photographs, illustrations, objects, and flyers, students will learn about the complex relationship between organized labor and civil rights activism, including efforts to desegregate labor unions as well as the role unions played in the fight for racial equality.

Student Goals

- Students will understand the history of segregation within workers’ movements of the 1800s that underpinned the fight for racial equality in 1960s labor unions.

- Students will learn about two central struggles between organized labor and civil rights activists in the 1963 CORE protests and 1968 UFT strikes, and analyze the issues activists highlighted in each fight.

- Through analyzing primary sources, students will discuss the various tactics and strategies activists used to address segregation in both schools and workplaces.

- Students will analyze and respond to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1968 speech “All Labor Has Dignity” to understand the relationship activists saw between racial justice and economic progress.

Common Core State Standards

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.5.3

Explain the relationships or interactions between two or more individuals, events, ideas, or concepts in a historical, scientific, or technical text based on specific information in the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.7

Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.9-10.2.F

Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the information or explanation presented (e.g., articulating implications or the significance of the topic).

Key Terms/Vocabulary

Affirmative Action, Boycott, Building Trades, Civil Disobedience, Civil Rights, Community Control, Discrimination, Integration, Labor, Segregation, Strike, Union

Key Figures

Ella Baker, Frank Ferrell, Reverend Milton Galamison, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., Mae Mallory, Rhody McCoy, Albert Shanker

Organizations

African-American Teachers Association (ATA); American Federation of State, Country, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME); Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); Knights of Labor; Ministers’ Committee for Job Opportunities; Parents in Action Against Educational Discrimination (PAAED); United Federation of Teachers (UFT)

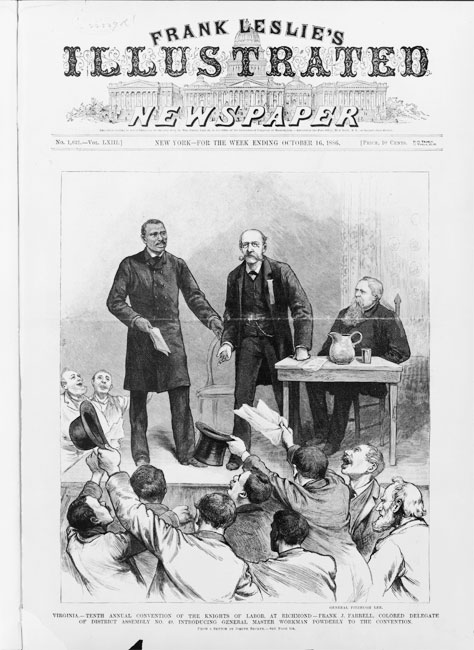

Introducing Resource 1: Illustration of black labor leader Frank Ferrell, 1886

New York City’s first labor movements began in the late 1700s and early 1800s as the industrial revolution changed the nature of work in urban spaces. Jobs formerly done by enslaved workers, indentured servants, and apprentices increasingly fell to free workers who sold their labor to employers. In 1827, as New York’s last enslaved people were freed, the city area’s 16,000 African Americans joined the free labor market in this expanding urban economy.

However, racism and poverty remained the norm for many black New Yorkers. As white workers formed labor unions to better negotiate with their employers, black workers faced systematic discrimination from many of these new organizations. A few labor movements welcomed black workers—black seamen and longshoremen struck alongside white workers for higher pay in 1802 and 1828—but resistance to black workers organizing persisted throughout the 1800s. In response, black working people in New York relied on their own churches, benevolent societies, schools, and social networks for aid in finding, negotiating, and keeping gainful employment and building wealth for themselves and their families.

Frank Ferrell was one of the few black New Yorkers who forged a place for himself in labor politics in the late 1800s. The city’s chief postal engineer, he was by the mid-1880s a central figure in the socialist wing of the city’s chapter of the Knights of Labor—one of the era’s largest labor organizations with nearly 1 million members nationally. The city’s chapter enrolled about 3,000 black workers and some Chinese New Yorkers as well out of its total 60,000 New York members. In this newspaper cover illustration from 1886, Frank Ferrell is shown introducing national leader Terence Powderly at the Knights’ annual convention in Virginia—a gesture of racial equality that enraged white Southern unionists, but also gained cheers from many of Ferrell’s white socialist New York colleagues who accompanied him to the convention.

Document-Based Questions

- Describe what you see in this illustration. What’s happening?

- How is Frank Farrell being depicted in this illustration?

- How is the crowd being depicted by the artist? What message about this event is the artist trying to convey?

- How might Farrell have felt addressing the crowd of mostly white union members?

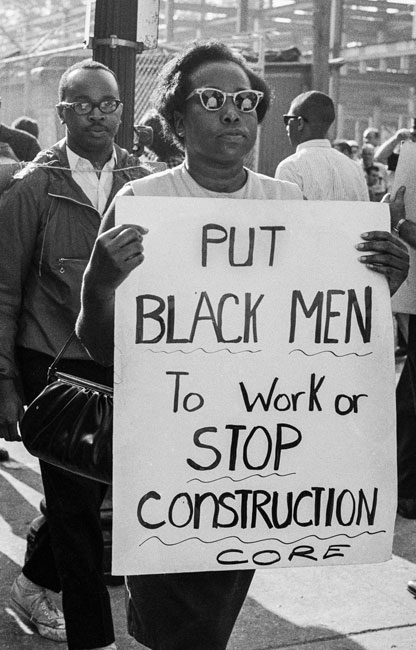

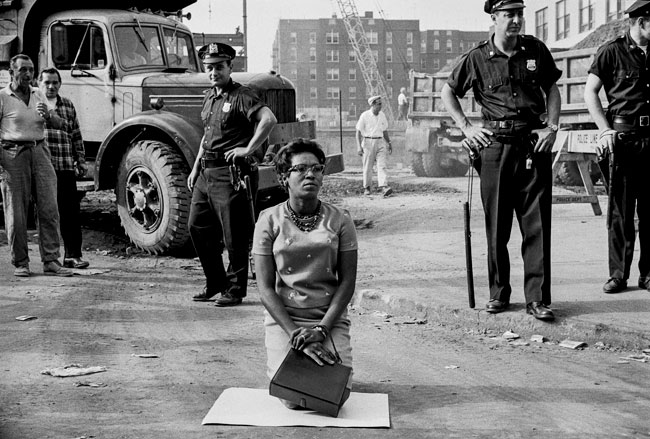

Introducing Resources 2 & 3: CORE protestors at the Downstate Medical Center construction site, 1963

Beginning in the late 1950s and on into the 1960s, New York City began to lose manufacturing and port jobs as businesses automated or moved away in pursuit of lower wages, lower taxes, and fewer regulations in other, less liberal parts of the country. As the supply of well-paying industrial and port jobs dwindled in New York City, activists in rising civil rights movements called for more opportunities for minority workers.

Throughout the 1960s, civil rights organizations led demonstrations to pressure construction and building trades unions into hiring black, Asian, and Latinx workers. These were jobs that had traditionally helped working white families move into the middle class and obtain economic security, but had historically been closed to people of color. Employers often pushed the responsibility of desegregation onto industry unions, which responded by keeping workers of color in the lowest paid positions on job sites, often called the “trowel trades.” Minority workers also had a difficult time getting admitted to the union-run apprenticeship programs that gave new workers training and thus a footing in the unions and the industry. Activists called for affirmative action programs to force unions to hire people of color and to diversify the construction and building trades industries.

On July 15, 1963, organizers and activists of the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), along with a coalition of Brooklyn ministers called the Ministers’ Committee for Job Opportunities led by the Reverend Milton Galamison, began picketing at the construction site of Downstate Medical Center in Flatbush, Brooklyn, protesting unfair hiring practices among the site’s unions. For three weeks, activists demonstrated at the site, demanding the immediate hire of black and Puerto Rican workers to represent at least a quarter of the workers on the site. Over 700 people were willingly arrested during the protest as activists blocked traffic and occupied the site. Malcolm X visited the protest, as did Jackie Robinson, who joined the picket line. Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese American civil rights activist who began her career as a journalist reporting from a wartime internment camp, was arrested as she protested.

On August 6, at a meeting arranged by New York State Governor Nelson Rockefeller, CORE won a promise from the site’s construction unions to create an apprenticeship program for African American and Puerto Rican workers. But the program did little to change the demographics of the city’s construction unions. Discrimination within the building trades remains an ongoing issue—in 2017, one of the city’s largest contractors, the Laquila Group, settled a lawsuit brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) charging the company with racial discrimination. They paid a settlement of $625,000 to six former employees. In the past 50 years, construction jobs for people of color in New York City have mostly expanded in the low-paid, non-unionized sectors of the industry.

Document-Based Questions

- Describe what you see in these photographs of the 1963 CORE protests. What’s happening?

- What expressions can you see in these photographs? What specifically might each of these individuals be feeling?

- In the photograph of the activist kneeling, what are the demographics of the individuals pictured?

- What is the goal of the protestor who is kneeling inside the construction site?

- In the photograph of the activist holding a sign, what does the sign say? What is the goal of this protestor?

- At the CORE protests, some activists marched and picketed, meaning they formed a crowd around the construction site to dissuade people from entering and to draw attention. Others disrupted work with the intention of being arrested. Why did activists utilize these various tactics? Which tactics are shown in these photographs?

- How might CORE have wanted passersby to feel as they observed this protest?

- What specific demands are these activists making?

Introducing Resource 4: Union pin memorializing Martin Luther King, Jr., 1968

Throughout the 1960s era of the civil rights movement, labor unions played a complex role. Many supported the struggle for racial justice and put money and organizing power behind the fight for equality, though some northern unions were far more willing to fund southern civil rights campaigns than invest in desegregation efforts within their own ranks. The New York City-based International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) supported the Montgomery bus boycotts, but faced lawsuits brought by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for systematic discrimination against its African American and Puerto Rican female garment workers. Other unions chose to maintain the status quo and resisted anti-discrimination laws and calls for desegregation within their ranks—New York City building trade unions were among the least welcoming of black members, but public unions that represented police and fire departments also remained overwhelmingly white.

Civil rights activists understood the immense power unions held over access to well-paying jobs for black Americans—a union contract was often a better tool for ensuring economic success than poorly enforced state and federal civil rights legislation. As Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote, “the coalition that can have the greatest impact in the struggle for human dignity here in America is that of the Negro and the forces of labor, because their fortunes are so closely intertwined.” King enjoyed close relationships with a number of New York-based unions, including DC 37, the city’s largest municipal public employee union; 1199, which represented healthcare workers; District 65, a “catch-all” union that organized low-paid and overlooked workers, including women, people of color, and recent immigrants; the TWU, the public transit union; and the UFT, which represents public school teachers. These unions, most of which were racially-inclusive, vigorously supported his campaigns for integration and equality in the South and across the country. This button from Local 420, which represents municipal hospital employees, memorializes King’s support for labor.

Document-Based Questions

- Describe the button pictured here. What do you notice about it?

- How might we interpret the phrase, “keeping the dream alive”?

- Why might a member of Local 420 choose to wear this button?

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was a strong supporter of labor rights and unions, writing that the “fortunes” of black workers and labor unions were “closely intertwined.” Why might he have felt labor rights were a civil rights issue?

- Given his stance connecting labor rights and civil rights, why might King have supported the right to unionize?

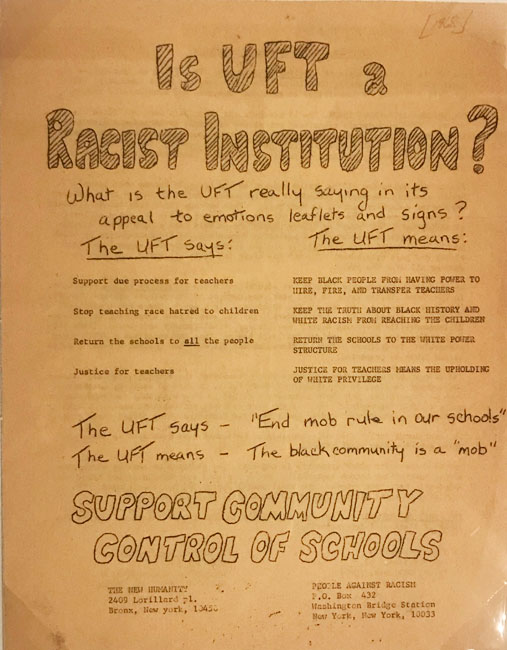

Introducing Resource 5: Flyer from the 1968 Brownsville teachers’ strike

In the 1950s and 60s, New York City civil rights activists led a series of campaigns intended to address educational inequality for African American and Puerto Rican students. Leaders of the protests included Ella Baker, a labor organizer and the NAACP director of branches; the Reverend Milton Galamison; and Mae Mallory, secretary of the Parents Committee for a Better Education in Harlem (later Parents in Action Against Educational Discrimination). A 1954 report issued by a progressive reform group, the Public Education Association, highlighted the main issues activists targeted: the majority of the city’s schools were “hyper-segregated,” meaning at least 95% of the school’s students were of one race; the city’s Board of Education spent considerably less per pupil for black students versus their white peers; and segregated black students performed on average two years below their grade levels.

Community organizers, parents, and students held school boycotts, lobbied political leaders, and filed lawsuits; they called for increased funding, a formal desegregation plan, better teachers, and “community control”—a policy where black and Puerto Rican communities gained oversight of administrative hiring and curriculum with the aim of including black history and culture. In 1967, Mayor John Lindsay authorized three school districts, including the Ocean Hill-Brownsville area of Brooklyn, to decentralize and allowed community-elected governing boards more authority, a practice called community control. The city’s public school teachers’ union, the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), opposed the policy, arguing that parents should not exercise authority over teachers or curriculum, especially since the UFT had fought hard to win a secure position for teachers in their daily work, free from outside pressures.

In September 1968, after the Ocean Hill-Brownsville administrator and community control activist Rhody McCoy fired 13 UFT teachers, the union struck for 36 days, shutting down the city’s public schools and keeping more than a million students home. In an escalating crisis, some black activists charged the union with waging “educational genocide” on minority students, while UFT president Albert Shanker accused the experimenters of anti-Semitism against his largely Jewish membership. Reactions to the strike were mixed among civil rights activists, city unions, and UFT teachers. Black and Puerto Rican labor leaders and the African-American Teachers Association (ATA) sided against the UFT in support of the majority black community governing board. Bayard Rustin, who had helped to organize a 1964 city-wide school boycott intended to publicize the problem of segregated schools, supported the strike in part out of his commitment to labor rights, but also because he believed that the idea of community control ran counter to the broader goal of integrating city schools. A city-brokered settlement ended the strike by terminating community control experiments but also left lingering wounds. The strike badly damaged relationships between black and Jewish activists, and damped enthusiasm for education reform for over 30 years. Shanker’s UFT went on to play a major role in organizing black and Latinx school workers so they could obtain bargaining rights, better pay, and better work conditions. But as of 2019, New York City schools are among the most segregated public school districts in the United States.

This flyer from the 1968 strike advocates for community control.

Document-Based Questions

- How does this flyer describe the UFT?

- After reading this flyer, what would you say the main goals of its author(s) are?

- How does this flyer imply the benefits of community control in schools?

- What do you think the author(s) of this flyer wanted readers to do after reading it?

- How might different audiences react after reading this flyer? Discuss how each of the following individuals might respond:

a. A UFT teacher

b. An Ocean Hill-Brownsville parent

c. An Ocean-Hill Brownsville student

Activity

Drawing upon what they have learned about the relationship between the civil rights movement and labor politics in the 1960s, students will read and analyze an excerpt from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s March 18, 1968 speech, “All Labor Has Dignity,” delivered in Memphis, Tennessee.

As part of his Poor People’s Campaign in 1968, King traveled to Memphis to support 1,300 black sanitation workers who were on strike after the city refused to acknowledge their right to collectively bargain. The workers were members of Local 1733 of the American Federation of State, Country, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). On March 18, King spoke to a crowd of over 10,000; on April 4, one day after returning to Memphis to join striking workers as they marched, King was assassinated.

Have students read this portion of the speech to themselves first, circling words or phrases that resonate with them; then, read King’s speech below slowly and deliberately. Before reading the speech aloud, ask students to imagine they are sitting in the audience at the church in Memphis where King delivered this speech, surrounded by members of the city’s public workforce.

After hearing King’s speech, ask students to write briefly (5-10 minutes) about their individual reaction to the speech, using one or more of the questions above to guide their analysis. Then, students should form small groups to discuss their reactions, before coming back together as a class for a final discussion and opportunity to share out.

- What is King’s basic argument?

- Did this speech have an emotional impact on you? If so, how?

- How does King characterize labor?

- What specific issues does King call attention to in this speech?

- What is King asking his audience and the city of Memphis to do?

- How does this speech change how you think about the civil rights movement?

- How does this speech change the way you think about work?

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “All Labor Has Dignity”

You are doing many things here in this struggle. You are demanding that this city will respect the dignity of labor. So often we overlook the work and the significance of those who are not in professional jobs, of those who are not in the so-called big jobs. But let me say to you tonight, that whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity, and it has worth. One day our society must come to see this. One day our society will come to respect the sanitation worker if it is to survive, for the person who picks up our garbage, in the final analysis, is as significant as the physician, for if he doesn’t do his job, diseases are rampant. All labor has dignity.

But you are doing another thing. You are reminding, not only Memphis, but you are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages. And I need not remind you that this is our plight as a people all over America. The vast majority of Negroes in our country are still perishing on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. My friends, we are living as a people in a literal depression. Now you know when there is mass unemployment and underemployment in the black community they call it a social problem. When there is mass unemployment and underemployment in the white community they call it a depression. But we find ourselves living in a literal depression, all over this country as a people.

Now the problem is not only unemployment. Do you know that most of the poor people in our country are working every day? And they are making wages so low that they cannot begin to function in the mainstream of the economic life of our nation. These are facts which must be seen, and it is criminal to have people working on a full-time basis and a full-time job getting part-time income. You are here tonight to demand that Memphis will do something about the conditions that our brothers face as they work day in and day out for the well-being of the total community. You are here to demand that Memphis will see the poor.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. “All Labor Has Dignity.” Speech. Bishop Charles Mason Temple of the Church of God in Christ, Memphis, Tennessee, March 18, 1968.

Sources

Cannato, Vincent. “The 1968 New York City School Strike Revisited,” Commentary, May 2018, https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/1968-new-york-city-school-strike-revisited/

Freeman, Joshua B., editor. City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York. New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.

Honey, Michael K. “Martin Luther King and Union Rights,” Clarion: Newspaper of the Professional Staff Congress/City University of New York (April 2011): 11, https://www.psc-cuny.org/clarion/april-2011/martin-luther-king-and-union-rights.

Kahlenberg, Richard D. “A School Strike That Never Quite Ended,” New York Times, November 17, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/17/opinion/teachers-strike-liberals-ocean-hill-brownsville.html

King, Jr., Martin Luther. “All Labor Has Dignity.” Speech. Bishop Charles Mason Temple of the Church of God in Christ, Memphis, Tennessee, March 18, 1968, https://www.beaconbroadside.com/broadside/2018/03/the-50th-anniversary-of-martin-luther-king-jrs-all-labor-has-dignity.html

Perillo, Jonna. Uncivil Rights: Teaches, Unions, and Race in the Battle for School Equality. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2012.

Purnell, Brian. Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings: The Congress of Racial Equality in Brooklyn. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2013.

Additional Resources

Honey, Michael K., editor. “All Labor Has Dignity”: King’s Speeches on Labor. Boston: Beacon Press, 2011

Juravich, Nick. “A Chalkbeat roundtable: What New York City is still learning from its teacher strikes of 1968,” Chalkbeat.org, October 18, 2018, https://www.chalkbeat.org/posts/ny/2018/10/18/a-chalkbeat-roundtable-what-new-york-city-is-still-learning-from-its-teacher-strikes-of-1968/

Nicols, John. “Dr. King Knew That Labor Rights Are Human Rights,” The Nation, April 3, 2018, https://www.thenation.com/article/dr-king-knew-that-labor-rights-are-human-rights/.

Poor People’s Campaign, 1968. Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, http://reuther.wayne.edu/image/tid/2068.

- This gallery contains a selection of photographs from the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign organized by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) that shows speeches and demonstrations, along with the camp created by protestors on the National Mall in Washington, DC known as “Resurrection City.”

Shapiro, Eliza. “Segregation Has Been the Story of New York City’s Schools for 50 Years,” New York Times, March 26, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/26/nyregion/school-segregation-new-york.html.

Taylor, Clarence. Civil Rights in New York City: From World War II to the Giuliani Era. New York: Fordham University Press, 2011.

Field Trips

This content is inspired by the exhibition City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York. Consider bringing your students on a field trip to visit this exhibition before January 5, 2020! Find out more.

Acknowledgments

City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York, its associated programs, and its companion publication are made possible through the generous support of The Puffin Foundation, Ltd.

The Frederick A.O. Schwarz Education Center is endowed by grants from The Thompson Family Foundation Fund, the F.A.O. Schwarz Family Foundation, the William Randolph Hearst Endowment, and other generous donors.