Civil Rights

New York and Civil Rights

1945-1964

Ongoing

Back to Exhibitions

In 1947, former Army Captain Joseph R. Dorsey and two other African-American veterans sued to obtain apartments in the new, whites-only Stuyvesant Town housing project on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Although their lawsuit was not successful, their case symbolized a new era in civil rights activism in New York City, which had become the world’s largest African-American urban community.

Following World War II, African-American New Yorkers and their allies mobilized against a range of discriminatory policies and practices, including exclusion by employers and banks, segregation of public schools, and controversial uses of force by police. While school segregation was officially outlawed after 1954, activists argued that the city tolerated inferior schools in Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brownsville, and other neighborhoods populated primarily by people of color, and they created the NAACP Schools Workshop to pressure the city to integrate public schools. The whites-only Stuyvesant Town housing project, which was ultimately integrated, comprised one of many campaigns against housing discrimination.

By the 1964 federal Civil Rights Act, New York had had passed anti-discrimination laws in employment and housing, and activists had staged an enormous school boycott protesting segregated schools. Yet racial discrimination remained, and that year, rioting broke out in Harlem after a white policeman fatally shot African-American teenager James Powell. Activists have continued to mobilize in response to police conduct in communities of color, as well as against city schools and housing that remain divided along racial lines.

Meet the Activists

Hardine Hendricks

Hardine Hendricks

In 1943, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company announced that no black tenants would be accepted at Stuyvesant Town, its new housing project being built with public support. Some residents of Stuyvesant Town resisted the whites-only policy by subletting apartments to black families. Here, Hardine Hendricks, whose family were the first African Americans to move in, receives a visit from white neighbors who supported the act of protest.

Image Info: 1949, © Bettmann/Corbis.

Milton Galamison

Milton Galamison

From his pulpit in Bedford-Stuyvesant’s Siloam Presbyterian Church, the Rev. Milton Galamison rallied his congregation to fight against school inequality, declaring that an equal education “is impossible in a segregated school.” Here, he escorts white children into a predominantly black school on the morning of his second school boycott. While over 400,000 stayed out of school on the first boycott, the second, on March 16th, saw less response.

Image Info: March 16, 1964, © Bettmann/Corbis.

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin

New Yorkers played key roles in the Southern civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, providing leadership, funds, publicity, and legal counsel. New Yorker Bayard Rustin planned the historic 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. His socialism and homosexuality, however, marginalized him within the leadership of the civil rights movement.

Image Info: U.S. News & World Report Magazine, August 27, 1963, Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsc-01272.

Ella Baker

Ella Baker

Ella Baker, who was a powerful force in the civil rights movement for decades, emphasized the importance of empowering everyday people. Baker led the New York NAACP’s education committee in the 1950s, before returning to the South to work with Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and to help found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Image Info: 1940s, Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Visual Materials from the NAACP Records, LC-DIG-ppmsca-38688.

Museum of the City of New York wishes to thank The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for authorizing the use of this image

Benjamin Davis

Benjamin Davis

Harlem voters elected lawyer and civil rights activist Benjamin J. Davis to the City Council in 1943. While he ran on the American Labor Party ticket, Davis was openly a member of the Communist Party. In 1951, he was convicted under the anti-Communist federal Smith Act; he spent five years in prison. Here, Davis and Robert Thompson, another Smith Act defendant, stand with supporters outside the federal courthouse in Manhattan’s Foley Square.

Image Info: 1949, Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection, LC-USZ62-111433.

Objects & Images

Residential Security Map For Section I, Uptown Manhattan

Residential Security Map For Section I, Uptown Manhattan

This government-sponsored map shows the local and national policies that shaped housing segregation. The map indicates the perceived risk of real-estate investments in upper Manhattan. The riskiest—marked red—typically indicated racially or ethnically mixed neighborhoods. While the New York State Legislature, and then the New York City Council, passed the nation’s first fair housing laws in 1950 and 1951, these “redlined” maps set bank lending patterns that continued for several decades.

Image Info: Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, April 1, 1938, Courtesy National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Picket Line In Front Of Empire City Bank

Picket Line In Front Of Empire City Bank

This protest was aimed at banks’ refusals to lend to African-American homebuyers seeking to move into white neighborhoods. One of the signs refers to the play On Whitman Avenue, in which African-American actor Canada Lee plays a character confronting bank-supported agreements to keep neighborhoods all-white.

Image Info: Attributed to Willard Smith, ca. 1946, Courtesy Prints and Photographs Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Campaign Flyer

Campaign Flyer

In his 1949 election to the City Council, Davis called on Democratic Mayor William O’Dwyer and Republican Governor Thomas Dewey to end racially discriminatory hiring in New York.

Image Info: 1949, Courtesy Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Questionnaire Distributed To Black Parents

Questionnaire Distributed To Black Parents

During the 1950s, Ella Baker, chair of the New York NAACP’s education committee, oversaw efforts to canvass African-American parents about conditions in their local public schools. Responses to this questionnaire were used by the NAACP to support its argument that the city’s schools remained racially separate and unequal.

Image Info: 1950s, Courtesy Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Museum of the City of New York wishes to thank The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for authorizing the use of this flyer.

School Boycott Flyer

School Boycott Flyer

This flyer for the citywide public school boycott emphasizes inferior conditions at segregated city schools. On February 3, 1964, more than 400,000 students boycotted New York City schools in order to protest the Board of Education’s failure to adopt an effective racial integration plan.

Image Info: 1964, Courtesy Elliott Linzer Collection, Queens College Civil Rights Archives, City University of New York.

“New York Freedom School, Freedom Diploma” Belonging To Civil Rights Leader Bayard Rustin

“New York Freedom School, Freedom Diploma” Belonging To Civil Rights Leader Bayard Rustin

School boycotts and a one-day program of racially integrated Freedom Schools in 1964 gained support from New York’s civil rights organizations but failed to force the city to integrate its schools.

Image Info: May 18, 1964, Courtesy Walter Naegle.

Untitled, New York

Untitled, New York

While a “Jim Crow” system of legal segregation is often thought of as unique to the American South, federal and local policies that shaped housing, employment, and schools made discrimination pervasive in New York and other northern locales.

Image Info: Bruce Davidson, 1962, © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos.

Flyer, “Missing Call Fbi”

Flyer, “Missing Call Fbi”

On June 21, 1964, three civil rights activists with the “Freedom Summer” project disappeared in Mississippi; their bodies were found in August. James Chaney grew up in that state, while Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman had traveled south from New York. Their murders, particularly those of white northerners Schwerner and Goodman, prompted international media attention and helped pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Image Info: Council of Federated Organizations, 1964, Courtesy Andrew Goodman Collection, Queens College Civil Rights Archives, City University of New York.

The Fatal Shooting Of Powell Stirred Negro Rioters To Race Through Harlem Streets Carrying Pictures Of Lt. Gilligan

The Fatal Shooting Of Powell Stirred Negro Rioters To Race Through Harlem Streets Carrying Pictures Of Lt. Gilligan

News media covered the rage of Harlem residents following the killing of 15-year-old James Powell by New York policeman Thomas Gilligan on July 16, 1964. The incident led to confrontations with police from July 18-22nd.

Image Info: Dick DeMarsico, July 1964, Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection, LC-USZ62-136895.

Civil Rights Buttons

Civil Rights Buttons

These buttons show how the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Quality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) used the courts, boycotts, voter registration, and civil disobedience to mobilize for racial equality in New York and nationwide.

Image info: 1940s-1960s, Courtesy Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

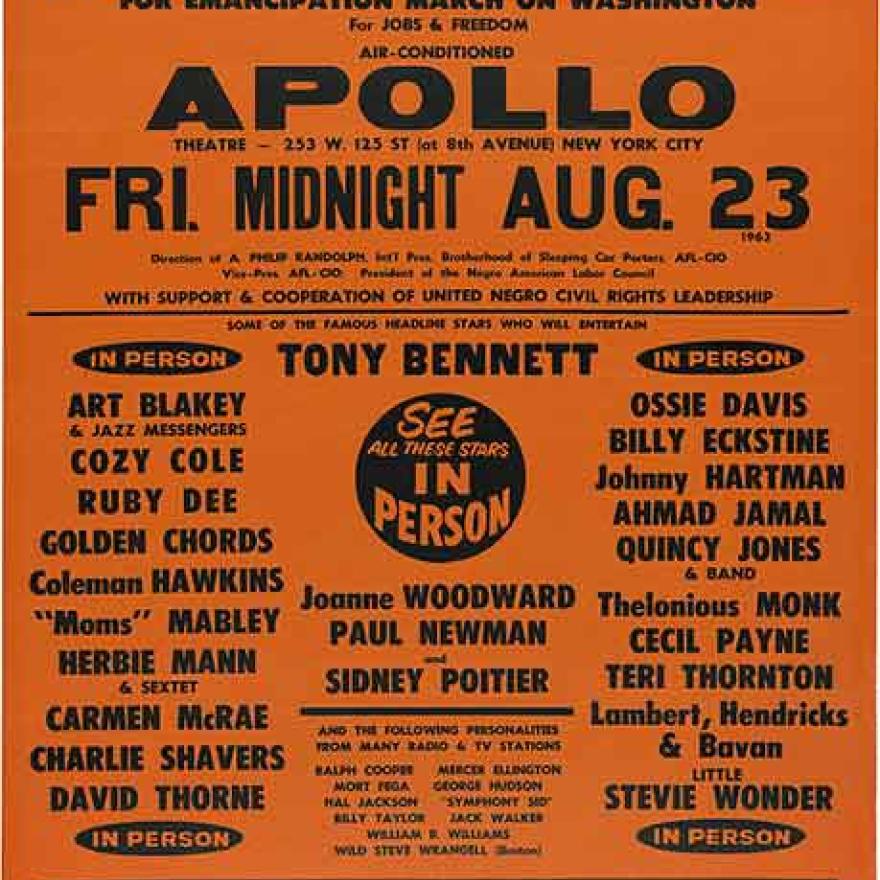

Poster

Poster

Stars ranging from Tony Bennett to “Little Stevie Wonder” turned out for a benefit concert at Harlem’s Apollo Theater to kick off the August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The benefit raised funds for jobless workers to travel to the Lincoln Memorial, where they heard speeches from multiple generations of social justice activists, including the legendary “I Have a Dream” by Martin Luther King Jr.

Image Info: Produced by the Negro American Labor Council; printed by Murray Poster Printing Co., Inc., Courtesy Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

Key Events

| Global | Year | Local |

|---|---|---|

|

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) founded in New York City |

1909 | |

| 1943 |

Benjamin J. Davis elected to the City Council to fill the seat of Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who becomes the first African-American New Yorker elected to Congress |

|

| 1947 |

Dorsey et al sue Stuyvesant Town after the 1943 announcement that it would not be open to black families |

|

| 1950 | New York State and then New York City pass fair housing laws to ban discrimination in publicly assisted housing | |

| 1956 | Two years after Brown v. Board of Education decision orders integration of schools, NAACP Schools Workshop formed to integrate New York City schools | |

| 1959 | Anti-school busing protest in Glendale, Queens | |

| Lunch counter sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina Ella Baker helps organize Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) | 1960 |

|

| Harlem resident Bayard Rustin organizes March on Washington | 1963 |